Nabeshima Ware

鍋島焼

Home > Fine Arts > Japanese Antique (To the Artworks Information Page)

Nabeshima Ware

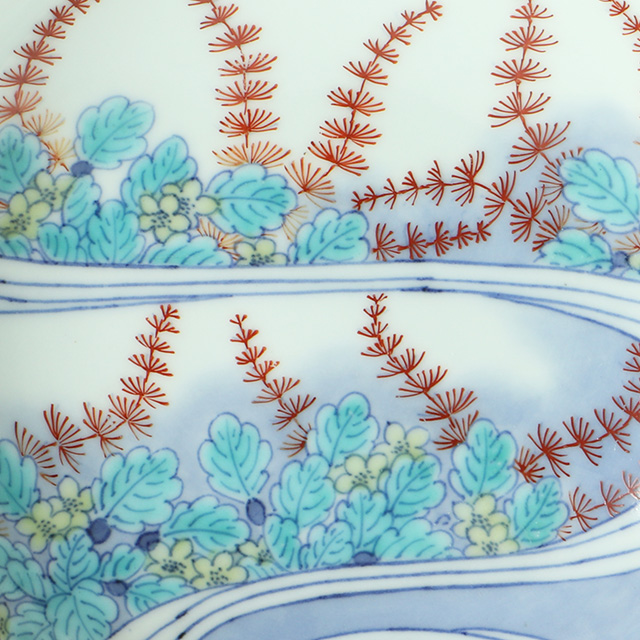

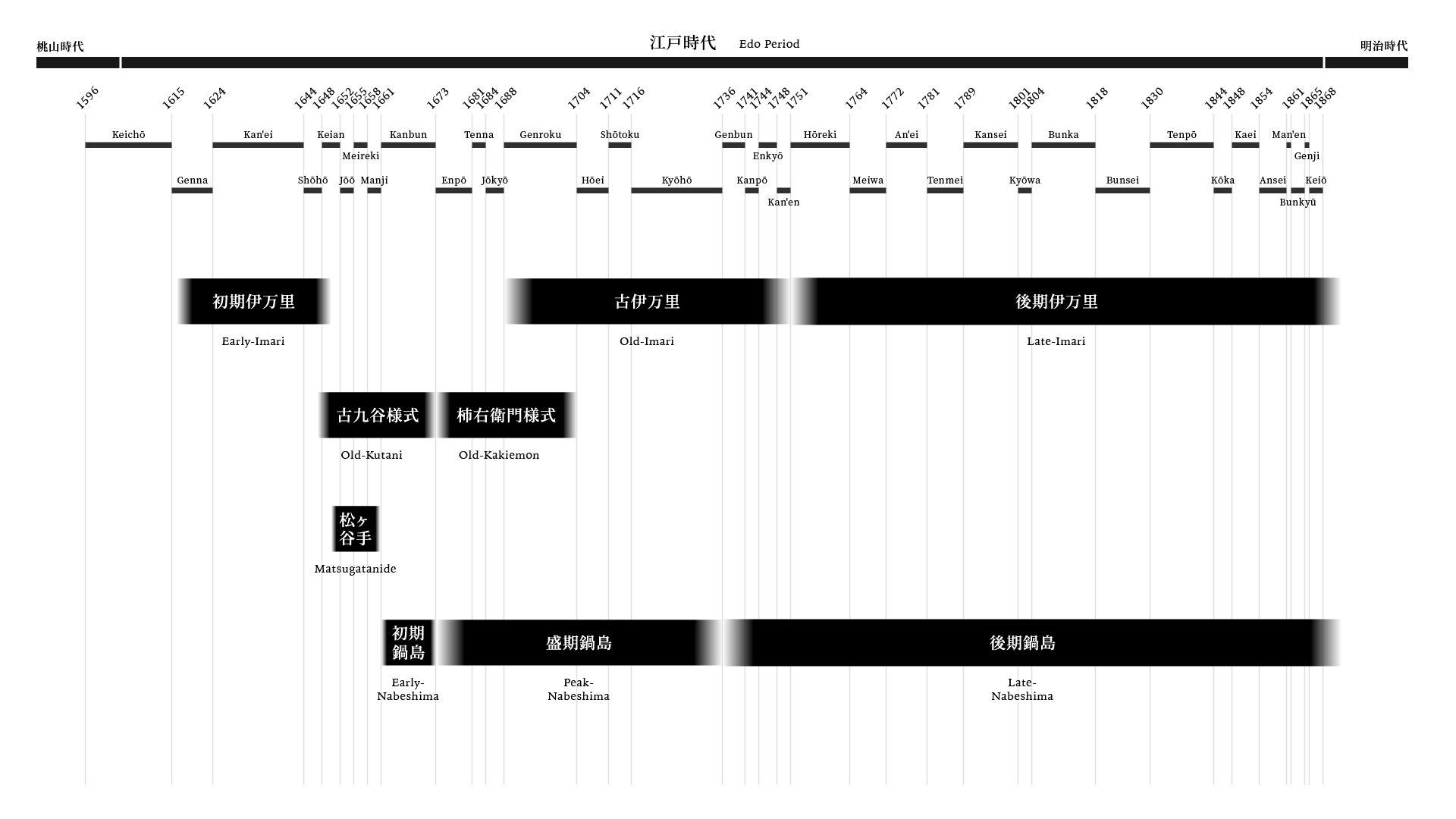

Nabeshima ware is a finely crafted and highly dignified porcelain specially commissioned and fired at the Nabeshima domain kilns in Okawachiyama, Matsuura District, under the patronage of the Nabeshima clan of the Saga Domain in Hizen Province. It is the only porcelain in Japan to possess the characteristics of an official kiln, and it stands as a world‑class masterpiece. Its technical refinement surpasses even the Kakiemon style, establishing an unparalleled reputation. The finest examples are often said to rival the imperial wares produced at China’s official kilns, a comparison that is by no means an exaggeration. Created as offerings to the shogunate—serving as proof of loyalty to the central authority of the bakuhan system—and presented to other feudal lords as symbols of amity, Nabeshima ware was never intended for commercial sale. Because production disregarded profitability entirely, these works were not distributed among the general public. The fundamental orientation of the domain kilns did not lie in tea ceramics but in practical vessels, especially dishes. In the Hizen region, ceramic‑producing areas were referred to as “yama,” and within the Nabeshima domain, the kiln dedicated to producing official wares was called the “Odogu-yama.” Selected master potters from various Hizen kilns were summoned to the Nabeshima kiln, where, in an isolated environment and under a strict organizational structure, a distinctive style was established. Records from the late Edo period note that 31 potters were employed, producing 5,031 pieces annually. A checkpoint was installed at the entrance to the kiln site, and passage by unauthorized individuals was strictly prohibited to prevent the leakage of secret techniques. Artisans working there were permitted to bear surnames and swords and were exempted from certain taxes. Production followed a division‑of‑labor system modeled after China’s official kilns, and even a single dish passed through the hands of numerous craftsmen. Offerings to the shogunate were produced with extras to account for breakage, and it is said that they were typically presented in sets of twenty. The early and mature periods saw the culmination of supreme techniques supported by exceptional craftsmanship. While works in underglaze blue and celadon exist, the most representative pieces are the “Iro‑Nabeshima” wares. Their method—drawing outlines in underglaze blue and applying overglaze enamels in red, green, and yellow—is considered to follow the “doucai” technique of the Chenghua era (1465–87) of the Ming dynasty, a level of refinement achievable only because the kiln operated without regard for cost. The designs shed Chinese and Korean influences, embodying instead a uniquely Japanese elegance. Motifs centered on plants of the natural world, along with landscapes, Noh costumes, and patterns drawn from Momoyama and Edo period painting manuals, crystallizing a beauty both graceful and noble. A representative vessel shape is the tall‑footed dish known as “wooden-cup form,” formed on the potter’s wheel. Compared with ordinary Arita folk kilns, the unusually tall foot is thought to have been intended to impart a sense of formality. Around the exterior of the foot, many works feature a distinctive underglaze blue pattern known as “comb-tooth pattern,” a technique permitted exclusively at the Nabeshima domain kilns and strictly forbidden elsewhere. Mature period works employ a meticulous method of shading (dami) within the underglaze blue outlines, but as time progressed, the lines gradually became less precise, eventually declining into simplified single‑line outlines. All products underwent rigorous inspection by multiple examiners, and only those that passed were delivered to the domain. Any defective pieces were completely destroyed. With the abolition of the feudal domains in 1871 (Meiji 4), the Nabeshima domain kilns were closed, bringing their distinguished history to an end.

Early Nabeshima from the Iwayagawachi Domain Kiln (Matsugatani-de)

Following the Battle of Sekigahara, Nabeshima Katsushige—the first lord of the Saga Domain in Hizen Province, who had sided with the Western Army (anti-Tokugawa faction)—sought to restore relations with the Tokugawa shogunate by presenting imported Jingdezhen porcelain from China. However, the dynastic upheaval caused by the Ming–Qing transition in 1644 (Shoho 1) disrupted porcelain imports from China. This crisis prompted an urgent need to develop domestically produced porcelain suitable for presentation to the shogunate. In response, the Saga Domain is believed to have commissioned the production of tribute wares at the Iwayagawachi Domain Kiln (also known as Odogu-yama) in Arita. By 1651 (Keian 4), prototype pieces had been completed and shown to the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu. This event is considered the beginning of the annual presentation of Nabeshima ware to the shogunate. The early Nabeshima wares produced at the Iwayagawachi kiln primarily consisted of Irregularly shaped small dishes and cylindrical choko cups, which have traditionally been classified as Matsugatani-de. Fragments of overglaze-decorated porcelain matching extant examples have been excavated from the Sarugawa kiln site in Iwayagawachi, supporting the attribution of these works to the Odogu-yama period prior to the kiln’s relocation to Okawachiyama. These early wares typically lack decoration on the reverse and bear no inscriptions within the footring. Their firing process, which leaves no spur marks, clearly distinguishes them from the folk kilns of Arita. The footring often features three carefully shaved facets, though over time this evolved into flatter, more rounded forms with softened edges. Biscuit firing and the use of saggars were essential to their production. In terms of overglaze technique, this was a period of experimentation, with underglaze blue and red linework used to define motifs and contours. By 1659 (Manji 2), Japan entered a full-fledged era of porcelain export through the Dutch East India Company (VOC). In the 1660s, the Odogu-yama kiln was relocated from Arita to the secluded mountainous region of Okawachiyama (present-day Imari City), in part to shield production from external influence. This transitional period, often referred to as the era of “Arita Nabeshima,” laid the foundation for the fully developed and regulated Nabeshima ware produced at the official domain kiln in Okawachiyama.

Key Characteristics of Early Nabeshima (Matsugatani-de)

- Biscuit firing was employed prior to glazing and decoration.

- The forms exhibit minimal warping, indicating careful shaping and controlled firing.

- The reverse surfaces are unsigned, with no inscriptions or marks.

- There are no spur marks inside the footring, suggesting a refined firing technique.

- The bearing surface of the foot (kodai tatami-tsuki) is shaved on three sides to prevent adhesion of kiln sand during firing.

- The group predominantly consists of irregularly shaped small dishes (approx. 15.0 cm in diameter) and cylindrical choko cups.

* Matsugatani-de refers to a group of wares—primarily irregularly shaped small dishes and cylindrical choko cups—that, while distinct from the Ko-Kutani style, share formal and glaze characteristics with early Nabeshima (Ko-Nabeshima) ware. These pieces were once attributed to “Matsugatani-yaki,” believed to have been produced in the Ogi Domain (a branch of the Saga Domain), and the term Matsugatani-de was widely adopted among collectors of early Japanese ceramics. However, recent multidisciplinary research has clarified that these wares do not, in fact, originate from the Matsugatani kiln.

Early Nabeshima

Early Nabeshima refers to the porcelain produced at the Nipposha-shita kiln in Okawachiyama between the 1660s and the 1680s. From 1659 (Manji 2), the Arita kilns entered a full-fledged period of overseas export, prompting the Saga Domain to reorganize its production system—most notably through the establishment of Akaemachi—to improve efficiency. As part of this restructuring, the official kiln responsible for producing special wares for presentation to the shogunate was separated from private kilns and relocated to Okawachiyama in Imari to prevent the leakage of technical secrets. Nipposha is a shrine dedicated to Nabeshima Naoshige, and the early domain kilns in Okawachiyama developed outward from the Nipposha-shita kiln located beneath it. Dishes from this period tend to have relatively shallow profiles, and the mokuhai-gata (wooden-cup form), which would later become standardized, begins to appear. Production expanded from small dishes to include medium-sized dishes as well. In addition to underglaze blue and overglaze enamels, a wide range of techniques—such as celadon, lapis-blue glaze, and iron-brown glaze—were employed. In overglaze decoration, black contour lines disappear, and red, green, and yellow enamels are applied within outlines rendered in underglaze blue or red. Common footring designs include Shiho-dasuki pattern, Hato pattern, Heart-linked pattern, Sawtooth pattern, Thunder-linked pattern, Sword-tip lotus-petal pattern, Shippo-musubi motif, Kushiba pattern—later dominant in the mature period—remains relatively rare. Footrings become taller, and decoration on the reverse side of dishes begins to appear. Although Early Nabeshima does not yet reach the refined perfection of the mature period, its unrestrained and vigorous expression—free from the strict standardization that would later define Nabeshima ware—stands as its greatest and most distinctive appeal.

Mature Period Nabeshima

The Mature Period Nabeshima refers to the porcelain produced at the Nabeshima domain kilns between the 1670s and the 1730s. In 1693 (Genroku 6), an official directive issued in the name of the second lord, Nabeshima Mitsushige, to the Arita Sarayama magistrate set forth a series of bold reforms. These included strict control over tribute wares and adherence to delivery deadlines; the creation of innovative porcelain by avoiding reliance on fixed, repetitive designs and by incorporating superior motifs from the private kilns of Wakiyama (Arita folk kilns); the prohibition of craftsmen from Wakiyama entering the domain kilns to prevent leakage of technical knowledge; the destruction of defective pieces within the kiln precincts; and the recruitment of highly skilled artisans from Wakiyama while dismissing those deemed incompetent. These measures triggered a major transformation in style. A close examination of the decorative motifs reveals many precedents in the Arita folk kilns. The comb‑tooth pattern with a fully painted footring can be traced to the Sarugawa kiln of the 1640s–50s, and the technique of bokashi‑dami (shaded overglaze coloring), perfected at the Kakiemon kiln and the Nangawarakamanotsuji kiln, appears in an even more refined form in Mature Period Nabeshima. Painting became increasingly pictorial in style, and techniques such as the introduction of the central negative‑reserve method were executed with remarkable precision. The period thus reached a pinnacle worthy of being called the apex of Japanese porcelain, distinguished by unparalleled technical mastery. Most of the representative iro‑Nabeshima pieces were produced during this era, and many large dishes—technically difficult to fire—were successfully made. The curves of the dishes maintain a beautifully balanced symmetry, while the reverse side typically features the prevailing combination of a comb‑tooth–patterned footring and a shippo‑musubi (linked seven‑treasures) design. In rare cases, gold decoration is also observed. According to records from the Kyoho era (1716–36), a total of eighty‑two items in five categories—large bowls (30.0 cm), large dishes (21.0 cm), medium dishes (15.0 cm), small dishes (9.0 cm), and choko cups—were presented to the shogunal household. The same number was delivered to the succeeding dainagon, and when combined with gifts to 35–41 senior officials of the shogunate, the total is said to have reached approximately 2,000 pieces.

Late Nabeshima

From the late Edo period onward, Nabeshima ware gradually lost some of its earlier technical precision, and works bearing date inscriptions or maker’s marks within the footring began to appear, reflecting a loosening of the strict production controls that had previously governed its manufacture. Tokugawa Yoshimune, the eighth shogun, implemented the Kyoho Reforms in an effort to restore the shogunate’s strained finances. In 1722 (Kyoho 7), an edict prohibiting luxury and ostentatious goods was issued, and in 1726 (Kyoho 11) the shogunate further decreed that, among the annual offerings of ceramics, pieces decorated with a wide variety of overglaze colors were to be restricted, while celadon wares could continue as before. This directive is regarded as marking the end of the Mature Nabeshima period. As a result, the polychrome Nabeshima wares—traditionally based on a tri‑color palette—disappeared, with underglaze‑blue wares becoming predominant, followed by celadon. Although a small number of red‑only or two‑color Nabeshima pieces were produced, no records confirm their use in the annual offerings to the shogunate. In late Nabeshima ware, the predominant reverse design became the peony‑arabesque (crab‑peony) motif. By contrast, works combining a comb‑tooth footring with a shippo‑musubi motif tend to be relatively less refined than those with peony‑arabesque designs, suggesting that they were likely produced as gifts or for domainal use rather than for the formal annual offerings. For the shogunal household, the peony‑arabesque motif was employed, while the shippo‑musubi motif was used for general gift‑giving and domainal purposes. In the closing years of the Edo period, a new fern motif—thought to have been intended for presentation to the Imperial Court—appeared. Furthermore, due to the financial strain placed on the Saga domain by the need to reinforce defenses in Nagasaki in response to the arrival of foreign ships, the domain petitioned the shogunate and was granted a five‑year exemption from the annual offerings in 1857 (Ansei 4).

Twelve Designs Favored by the Shogunal Household

In 1774 (Anei 3), during the tenure of Tokugawa Ieharu, the tenth shogun, the Saga domain received instructions regarding the annual offerings of ceramics: among the five types of wares presented each year, two or three were to be selected from a set of twelve designated designs. These twelve designs were as follows:

Large dish with plum design, Medium dish with peony design, Large chrysanthemum‑shaped square dish, Medium square dish with landscape design, Long rectangular dish with landscape design, Long rectangular dish with distant‑mountain and mist design, Long rectangular dish with folding‑cherry design, Boat‑shaped dish with goldfish design, Medium round dish with bush‑clover design, Chrysanthemum‑shaped dish with grape design, Mokko‑shaped dish with vine design, Sake cup with pine‑and‑plover design

Nabeshima Celadon

Since the Kamakura period, celadon ware imported from China—karamono—has been held in particularly high esteem in Japan. One explanation for why the Saga domain relocated its official kiln from Iwayagawachi in Arita to Okawachiyama is the belief that high‑quality celadon stone could be quarried there. It was in this environment that the clear, refined, and truly exceptional Nabeshima celadon—among the finest ever produced in Japan—came into being. In early Nabeshima ware, celadon glaze was often employed simply as one variety of colored glaze. From the mature period onward, however, celadon pieces became the predominant form, and the finest examples radiate an elegant green reminiscent even of kinuta celadon. Celadon achieves its depth of color through the repeated application of glaze layers, each requiring a separate firing, a process that inevitably entailed considerable risk. Whereas conventional celadon typically involved the application of a single celadon glaze, Nabeshima celadon includes highly sophisticated works—unparalleled anywhere in the world—that combine celadon with underglaze blue or overglaze enamels. In celadon‑underglaze‑blue pieces, the body is coated with celadon glaze at least twice, the design is then painted in cobalt, and yet another layer of celadon glaze is applied before firing. This meticulous and deliberate process requires no fewer than three firings. Because Nabeshima ware functioned as an official kiln producing gifts for the shogunate and various feudal lords, economic considerations were disregarded even in the demanding production of celadon.

Annual Tribute

In 1651 (Keian 4), a prototype completed that year was presented for inspection to the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu. This occasion is considered to have prompted the commencement of annual tribute of Nabeshima ware from the following year. The annual tribute was a system in which feudal lords throughout the country offered products from their domains in designated months, according to their assessed rice stipends. It is inferred that the Saga Domain’s annual tribute each November had already been practiced by at least the early eighteenth century. A record from 1770 (Meiwa 7) states that the offerings consisted of two large bowls (30.0 cm), twenty large dishes (21.0 cm), medium dishes (15.0 cm), twenty small dishes (9.0 cm), and a set of twenty teabowl saucers and choko cups, totaling five boxes. The dishes, produced in sets of twenty, are thought to have borne identical designs as coordinated tableware. In addition to the annual tribute to the shogunal household, Nabeshima ware was also presented to high-ranking officials of the shogunate, various retainers connected to the Saga Domain, and even to relatives. For this reason, it is presumed that a considerable number of works sharing the same designs were produced. However, many have since been dispersed, and examples that allow us to envision their original form as complete sets of tableware are exceedingly rare today.

We sell and purchase Nabeshima Ware

We have a physical shop in Hakata-ku, Fukuoka City, where we sell and purchase "Nabeshima Ware" works. Drawing on a long career and rich experience in dealing, we promise to provide the finest service in the best interests of our customers. With the main goal of pleasing our customers, we will serve you with the utmost sincerity and responsibility until we close the deal.