細川護光

Morimitsu Hosokawa

44,000Yen(Tax Included)

33,000Yen(Tax Included)

細川護光

Morimitsu Hosokawa

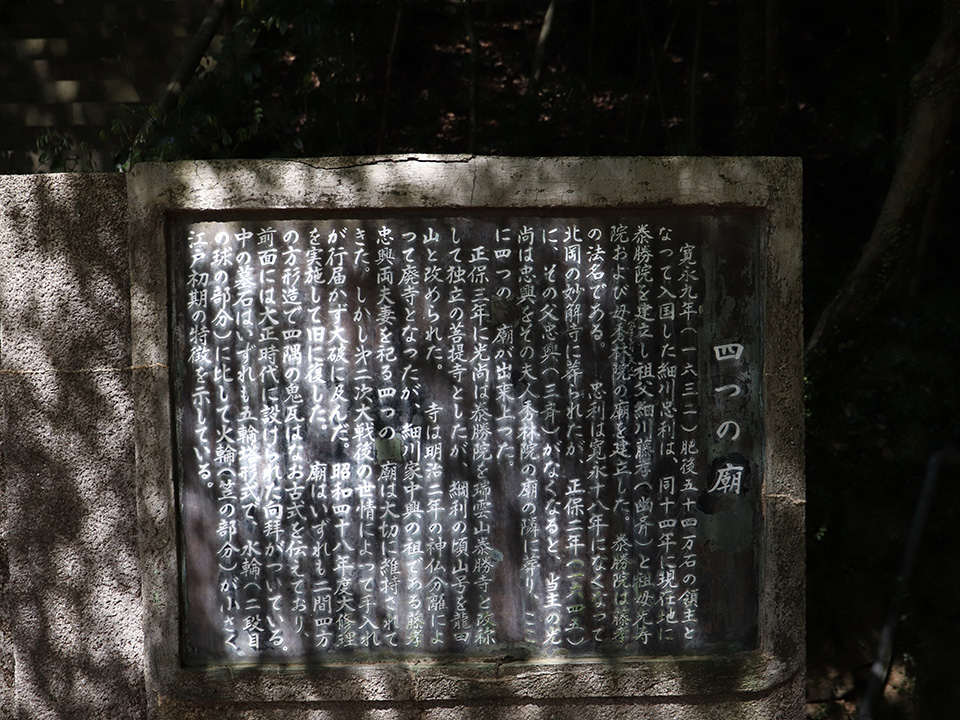

It was a sunny day in late march when the cherry blossoms were in full bloom about 10 days earlier than usual when we visited the tatsuta villa of the hosokawa clan, known as the “Taishoji Ruins. ” Taishoji was the temple of the hosokawa clan since it was built in 1636 by Tadatoshi Hosokawa, the first feudal lord of the kumamoto domain in higo province, until the separation of shintoism and buddhism in the early meiji period. In the precincts, the mausoleums of Fujitaka Hosokawa(Yusai), the founder of the hosokawa clan, and his wife, Kojuin, and Tadaoki Hosokawa(Sansai), and his wife, Garasha, are enshrined.

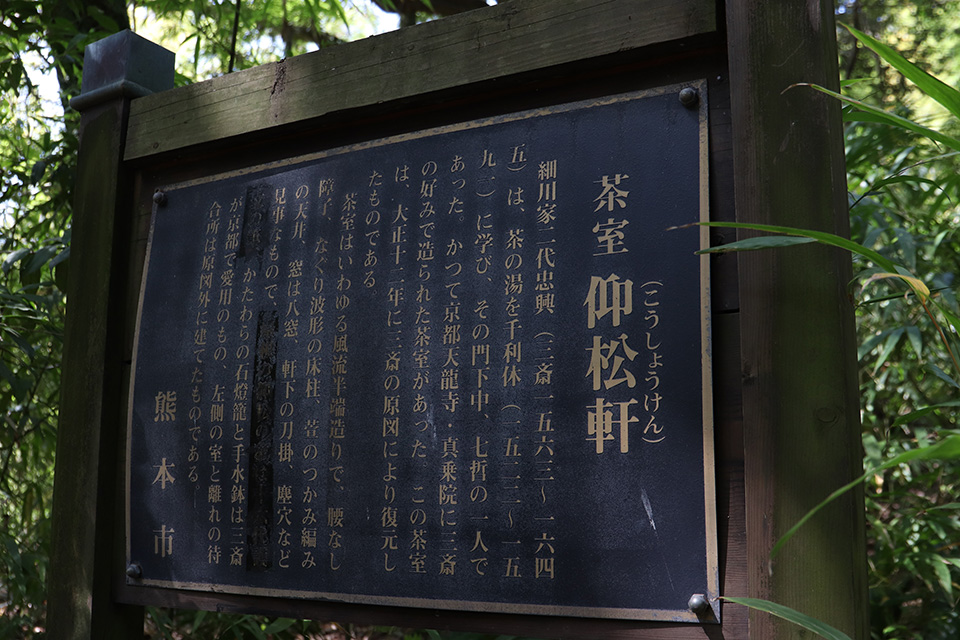

In addition, “Gyoshoken”, which was built in tatsuta nature park adjacent to the taishoji ruins, is the tea room built in 1923 based on the drawings left by Tadaoki. The chozubachi placed in the front garden was used by Tadaoki in kyoto, and is said to have been used by the tea master Sen no Rikyu.

Morimitsu Hosokawa, who lives in the historical taishoji ruins and works hard on pottery, will eventually succeed his father, Morihiro Hosokawa, and become the 19th head of the hosokawa clan. Born into one of japan’s most prestigious clans, Morimitsu has a natural and quiet air without feeling a heavy responsibility to carry on the tradition.

For the past few years, he has enjoyed making raku tea bowl. “Black Raku” has a dull luster, and “Red Raku” has a deep expression based on pale pink. When you pick one up, you can feel the warmth and softness of the soil.

When I asked, “What is the fun of hand twisting?”, he replied, “Unlike the potter’s wheel, it’s interesting that you can spend time on each work.” In particular, the black tea bowl is fired one by one in the kiln, so it takes more time and effort, but it seems that they are enjoying even that time and effort. “Raku ware is soft and brittle compared to other pottery. However, because it is soft, the heat is transferred slowly. It also has the advantage of making matcha delicious. When fired at a high temperature, the softness of the bowl is lost. That’s the difficult part,” said Morimitsu. Regarding the modeling, “I don’t decide from the beginning to make it, but I think that the things I’ve seen and the works I’ve picked up have remained in my consciousness, and that’s the basis. When you move your hands, it feels like it’s done before you know it,” he explained. Instead of pursuing the image that pops into his head, his hands subconsciously search for and reproduce the “form” that is hidden in his memory. The “Memories” cultivated by the hosokawa clan may be what motivates Morimitsu. Such a thought suddenly crossed my mind.

He had always wanted to work in an environment surrounded by nature, so he took over the land that his father owned and opened the kiln in kugino, minamiaso village in 2007. During the 2016 kumamoto earthquake, the kiln was destroyed, but the kiln craftsman came from arita to repair it.

The kiln, which is built against a thicket of trees, has an atmosphere that is clearly different from that of the taishoji temple ruins. The kind of generosity and calm that pervades his works is probably brought about by the creative environment in which he can feel nature with all five senses.

Come to think of it, his master was Masatake Fukumori, who runs “Doraku kiln” in the woodland of iga, mie prefecture. His style of reflecting the blessings of nature in his works may have been inherited from his teacher. “My teacher’s philosophy was that utensils should be used, not just looked at, and that had a huge influence on me, ” he says, adding that he also uses his own utensils for meals. He sometimes receives advice from his wife, Ai, who is a cooking expert. The vessels used to serve food do not just have to be beautiful. If it’s something you use every day, it must be easy to handle. “I think appearance also plays a part in ease of handling,” he says. If you think about it, the greatest mission of tableware is to enhance the food. It makes no sense to separate form and ease of handling. The philosophy of his teacher, Masatake Fukumori, was alive in his casual words.

This year marks his 16th year of making pottery, which he started because he wanted to make things and wanted to do something that involved physical activity rather than a desk job. “Even now, I get excited before I open the kiln. But when I open the kiln, there’s a 90% chance that I’ll be disappointed” he says, adding that because he’s so particular about the original soil, things often don’t go as planned. Using a blended soil would make it more stable, but it would also “become closer to an industrial product.” He finds it more interesting to use the original clay, which clearly reveals individuality.

He enjoys the long time span from creating a shape to firing it, enjoys the time and effort that goes into each work, and enjoys being influenced by the original soil and enjoying the fact that things don’t turn out as planned. Because he approaches his pottery like a treetop swaying in the wind without rushing, without rushing, and without forcing himself, his works convey a dignified dignity as well as a natural lightness.

“I don’t think I want to keep my work in my hands. Once I know the results of what I tried while creating it, it becomes complete in my mind”. When asked about his thoughts on his work, he replied. “Rather, I’m thinking about what’s next, what to do next. There’s no end point in this kind of work. The more you do it, the further the road will get.”

There is always a future ahead of him. Therefore, even though he inherits the hosokawa clan’s traditional aesthetic sense and cultural DNA, he is not bound by it. His pottery is free and flexible.

Morimitsu Hosokawa

細川護光

1972-

Born in tokyo and spent his childhood in kumamoto.

In 1999, studied under 7th Masatake Fukumori of “Doraku kiln” in iga city, mie prefecture.

In 2006, opened the kiln at “Taishoji” in kumamoto city.

In 2007, built the kiln in kugino, minamiaso village, kumamoto prefecture.

In 2008, first solo exhibition in kyoto. Since then, held solo exhibitions all over the country.

Worked on raku, shigaraki, korai, etc. And also served as director of eisei bunko.

Photography:Akira Eto / Takashi Imabayashi

Text:Kazuyoshi Hasegawa

The Path to Making Pottery

- QI heard that you made pottery for the first time when you were in high school.

- AThe first time I made pottery was in an art class when I was in high school. At that time, I wasn’t thinking about making pottery as a career.

- QHow did that lead to the path of making pottery.

- AI’d like to have a job where I can make things myself. That’s because I wanted to do a job that involved physical activity rather than sitting still in front of a desk.

- QIt seems that you also had some interaction with Jiro and Masako Shirasu.

- AI think I’ve met mr. Jiro before, but I don’t remember it since I was very young. I met mrs. Masako from time to time in her later years. For about a year, I even lived at buaisou in tsurukawa.

- QWere you influenced by Masako Shirasu’s aesthetic sense.

- AI was very influenced by it. Masako likes antiques, and she used them in her daily life. I learned a lot, and thanks to her, I started looking at antiques as well.

- QAfterwards, you will study under Masatake Fukumori in iga. Why did you choose mr. Fukumori as your teacher.

- AWell, it was because I had known him well since high school, and he was someone I had a lot of respect for. It was there that I wanted to learn pottery.

- QWhat kind of person is mr. Fukumori.

- AHe is easy going and drinks a lot of alcohol.

- QWhat did you learn from mr. Fukumori.

- AHis idea was that vessels should not only be looked at, but also used, which had a huge influence on me.

Creation in Four Kilns

- QWhy did you choose kumamoto when opening your own kiln.

- AI’ve always wanted to make pottery in kumamoto someday. Unless something like this is done in a local area, it cannot be done in tokyo.

- QDoes the type of pottery you make change depending on the location.

- AWell, I guess that’s true. The materials change, and the way I feel about it also changes a lot. The kilns in aso are especially relaxing because they are close to nature.

- QWhat kind of things are fired in aso’s kilns.

- AFor example, there are many works by yakishime. When it comes to glazed works, there is ash glaze. There is also a little kohiki afterwards.

- QWhat kind of things are fired in the kiln at the ruins of taishoji temple.

- ASince we only have a small electric kiln, I mainly fire kohiki. Basically, it is the kiln exclusively for bisque firing. I sometimes bisque fire something over there and then bring it here and fire it.

- QIt’s also fired at futoan in yugawara, where your father Morihiro Hosokawa lives, right.

- AOutside of kumamoto and yugawara, we have a kiln in nagano, where we fire twice a year as well. Ido and raku are yugawara. Shigaraki is fired in the kiln in nagano.

Footprints as a Potter

- QIt has been 16 years since you opened your kiln in kumamoto. Has your style changed.

- AI think things have changed. If the glaze or soil changes, the firing method will also change. I guess the soil is the most important thing. I often decide to bake something this way based on the soil. There are baking methods and shapes that are appropriate for the soil.

- QHow do you obtain soil.

- AI know a few soil companies that listen to my preferences, so I buy my soil from them. I feel that if you use blended soil instead of raw soil, it will be averaged out and become more like an industrial product. The great thing about the original soil is that each soil has its own unique characteristics.

- QDo you also use soil from kumamoto.

- APreviously, I used to go all over kumamoto myself and dig soil. I bought a geological map and guessed it. I also go to old-kiln and investigate areas where I think there were kilns in the past. When you go to the local museum of a particular area, you will find many stories about old-kiln sites, such as that there used to be a kiln in this area, or that tiles were fired there. I compare such stories with old maps, go to the area and dig in the soil. Nowadays, I don’t have to dig the soil myself much anymore.

- QIt seems like you’ve been focusing on hand twisting for the past few years. What’s the appeal of it.

- AIt’s a different method than using a potter’s wheel, and it’s very interesting to take time and care to make each piece.

- QIs there a difference in firing between black raku and red raku.

- ARegarding the firing method, the black one is fired one by one in the kiln, which takes more time and effort.

- QHand twisting means that mr. Hosokawa shapes each piece by hand, but is there anything important about the texture or shape.

- AIt’s not like I set out to do this from the beginning. I think that the things I have seen and held in my hands somehow remain in my consciousness, and that is what gives form to me. When I move my hands, I can do it without even realizing it.

The Look Towards the Future

- QHow do you feel when you open the kiln after your pottery is finished firing.

- ABefore I open the kiln, I’m in a dream state, or rather, I’m looking forward to it, but when I actually open the kiln lid, there’s a 90% chance that I’ll be disappointed. Among them, I feel that some works that I am satisfied with remain.

- QWhen you say “it didn’t work out,” do you mean that it didn’t reach the level you wanted.

- AYes. Well, sometimes the ingredients don’t bake as expected. Sometimes this job is fun, and sometimes it’s not. It’s a lot of hard work.

- QWhat is your favorite piece of work that you create.

- AIn my case, once a work is finished, I don’t really look back. My head is filled with thoughts of what to do next. That’s why I don’t even want to keep my own works in my hands. Once I know the results of the things I tried while creating, I feel complete in my mind.

- QIt is important to increase your experience value.

- AYes. Pottery is not something that will give you instant results. The time span from creating the shape on the potter’s wheel until it is fired is extremely long. You spend time firing it, look at the result, think about what to do next, make it again, look at the result, and then go on to the next thing. There is no end point in this kind of work. The more you do it, the further the path will get.