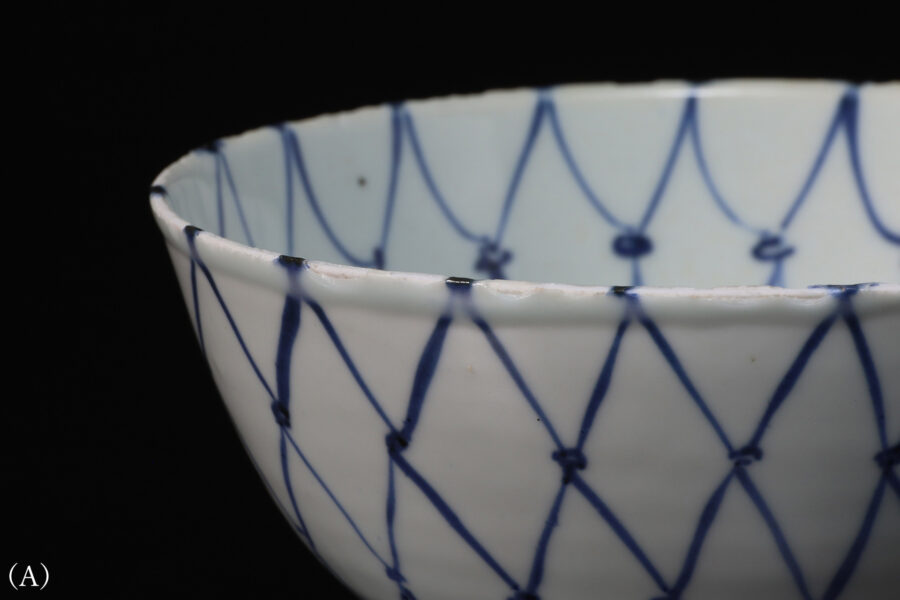

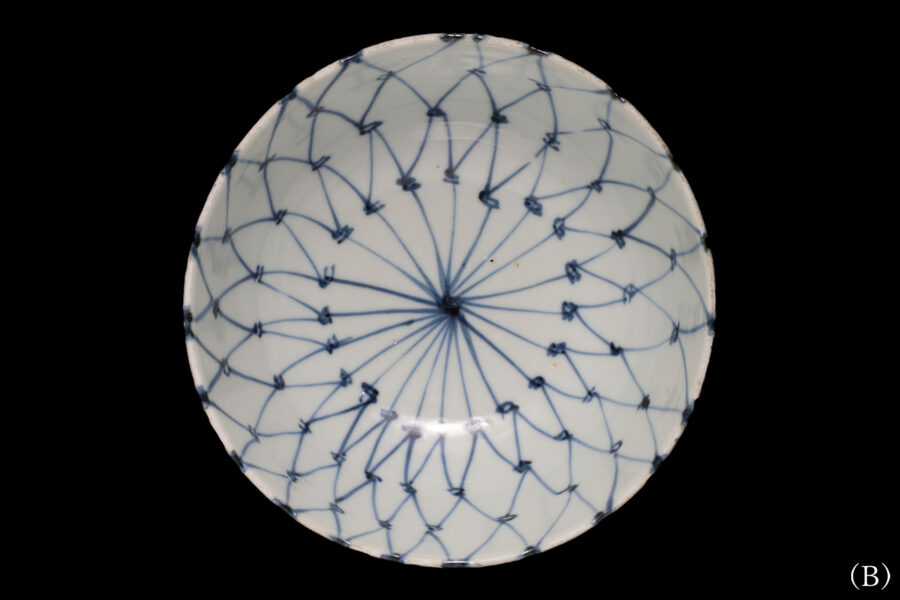

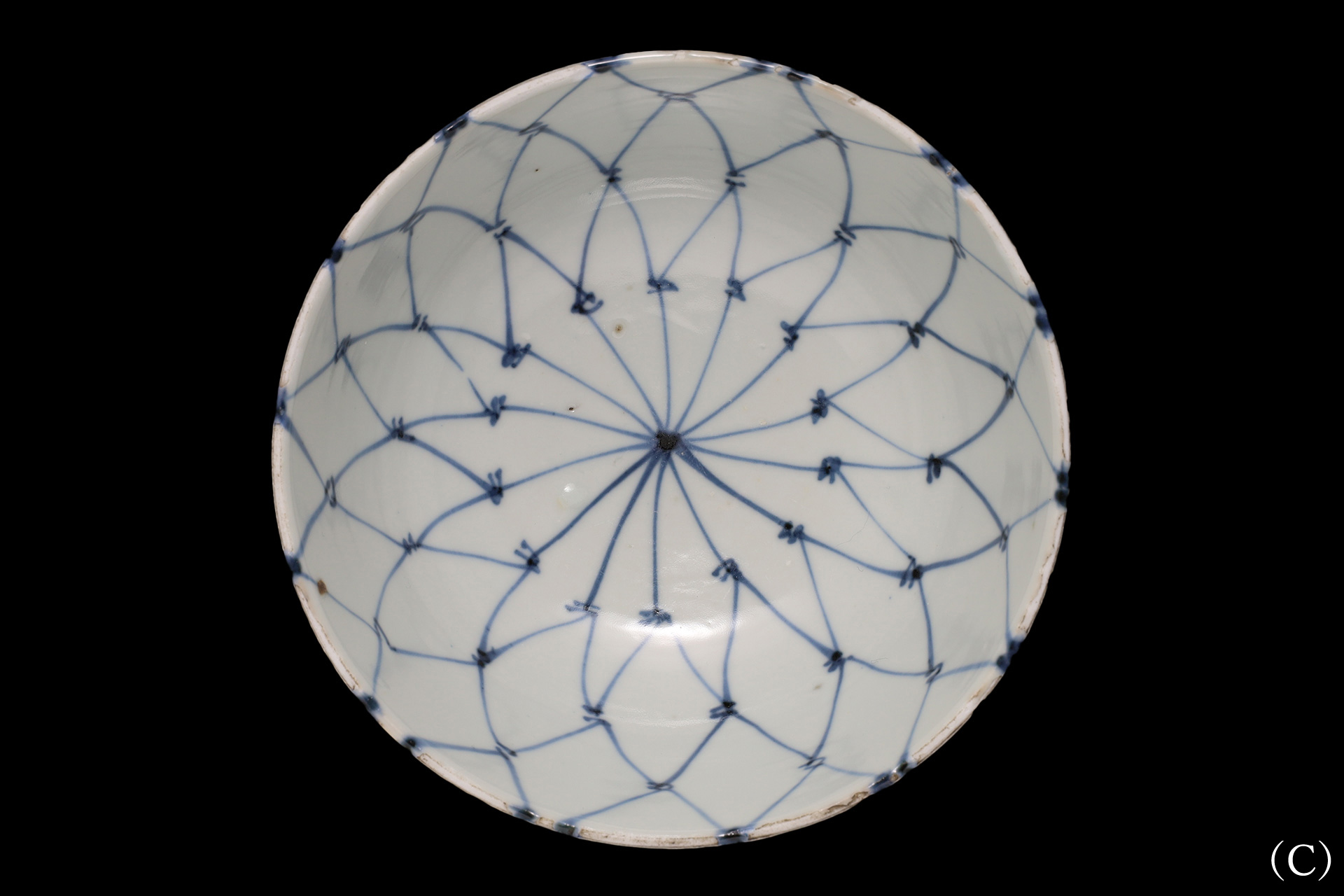

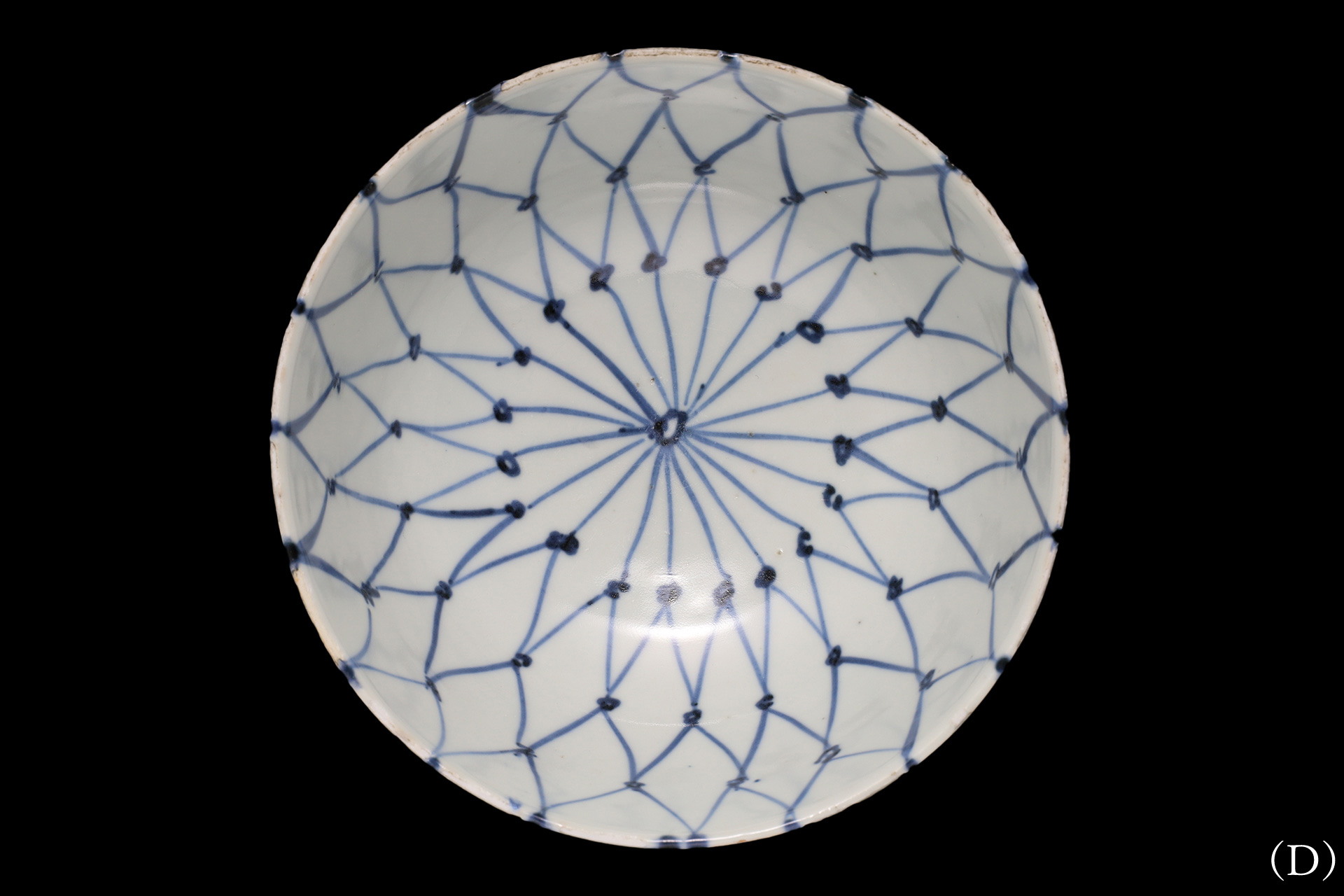

Set of Five Ko-Sometsuke Small Bowls with Net Design (Ming Dynasty)

Sold Out

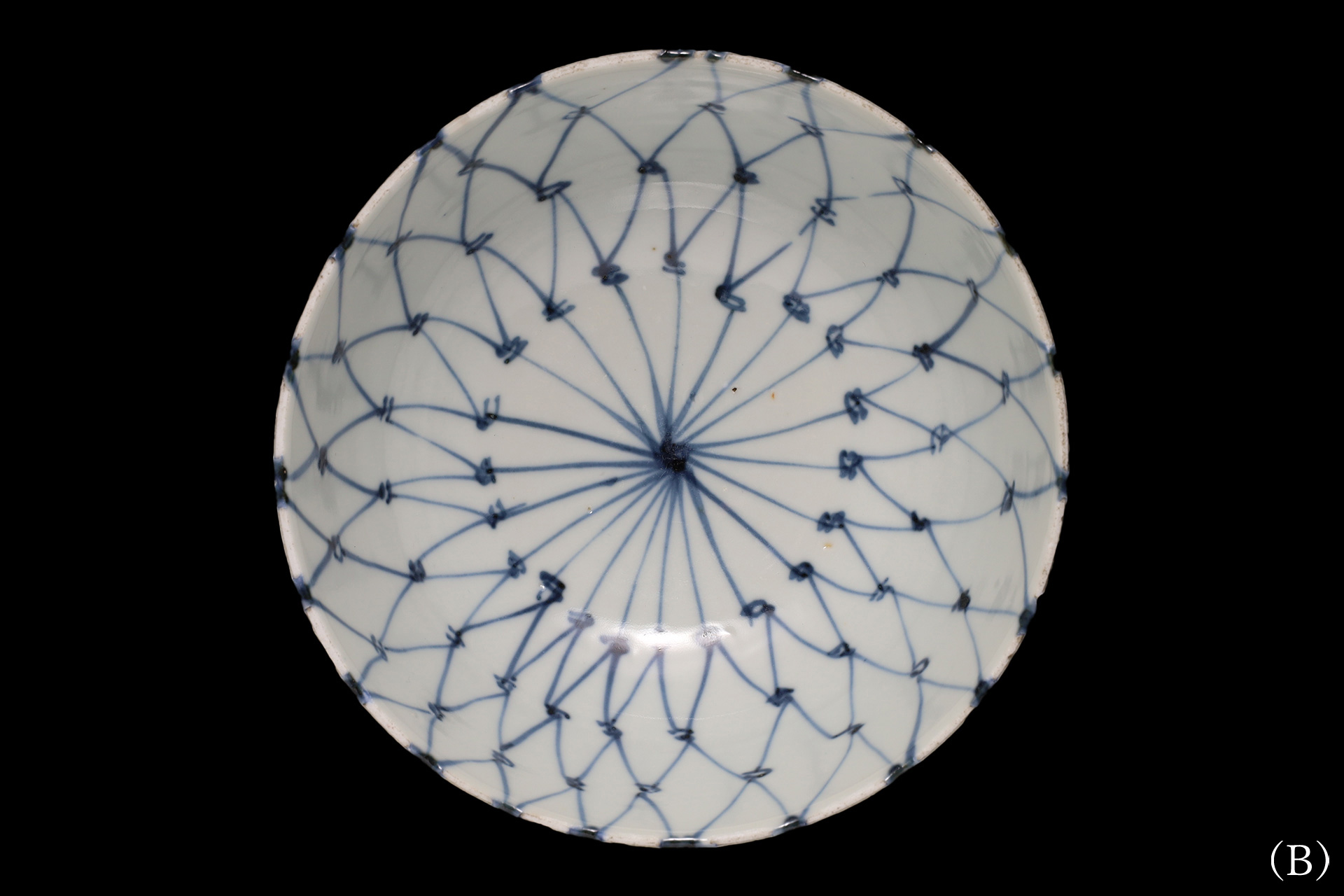

This is a rare set of five small bowls featuring the ami-de (net-pattern) design, fired at the Jingdezhen kilns in the late Ming dynasty. The intricate net motif, believed to “entwine wishes and bring them to fulfillment without loss,” envelops the entire surface of each vessel—front and back—in an unbroken, continuous weave. Revered for both its symbolic meaning and visual elegance, this design has been faithfully reproduced across generations. Commissioned by a Japanese tea master as a bespoke order, the set continues to quietly captivate hearts even after nearly four centuries.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 250902-1

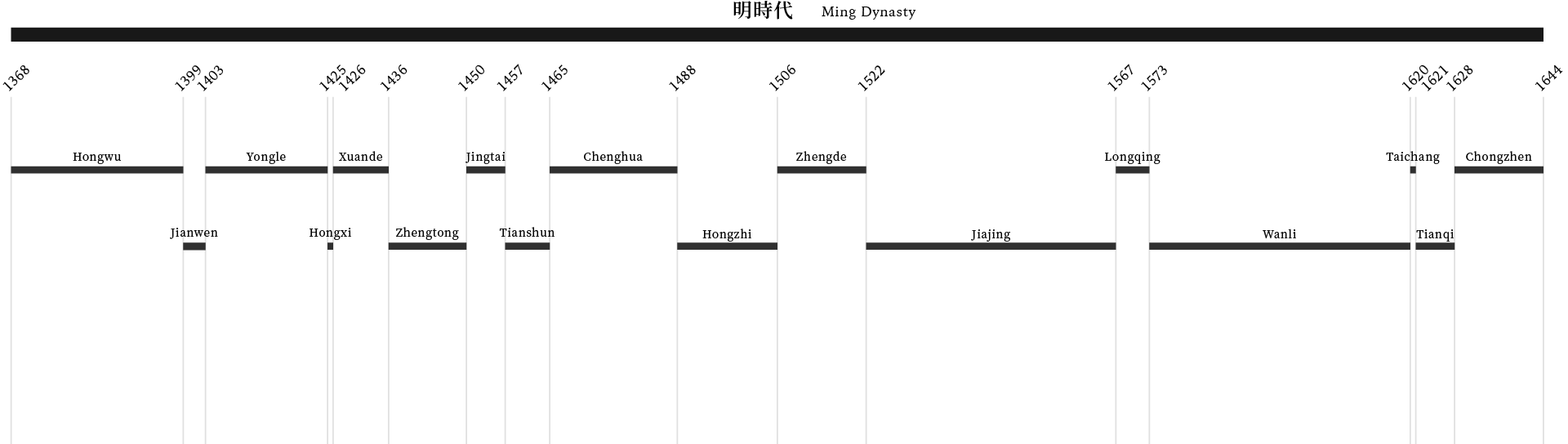

- Period

- Ming Dynasty

Early 17th Century

- Weight

- Approx. 166g per piece

- Mouth Diameter

- Approx. 12.1cm

- Height

- Approx. 6.2cm

- Base Diameter

- Approx. 4.8cm

- Fittings

- Paulownia Box

- Condition

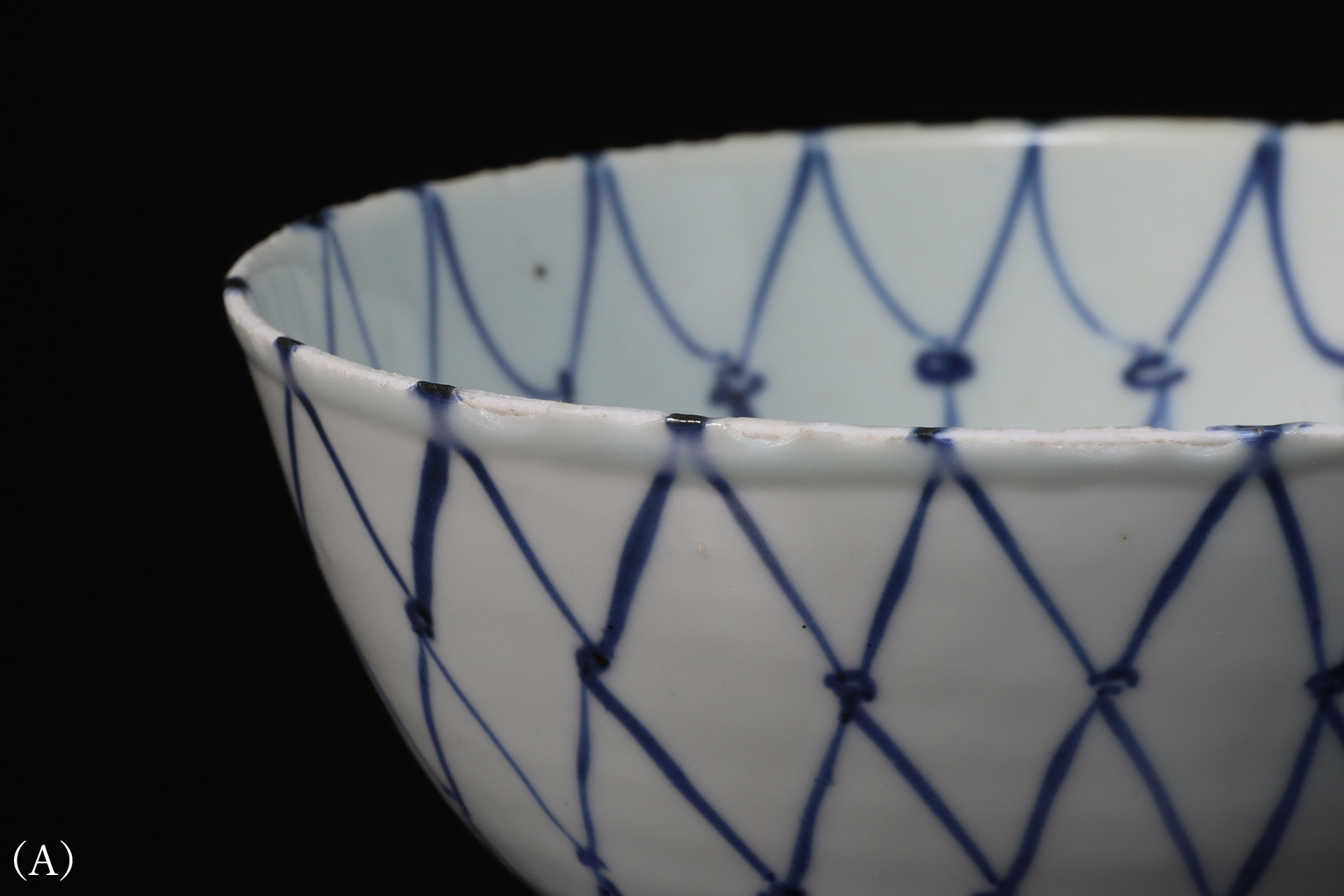

- ・3 bowls (A-C): Intact (There are mushikui on the rim)

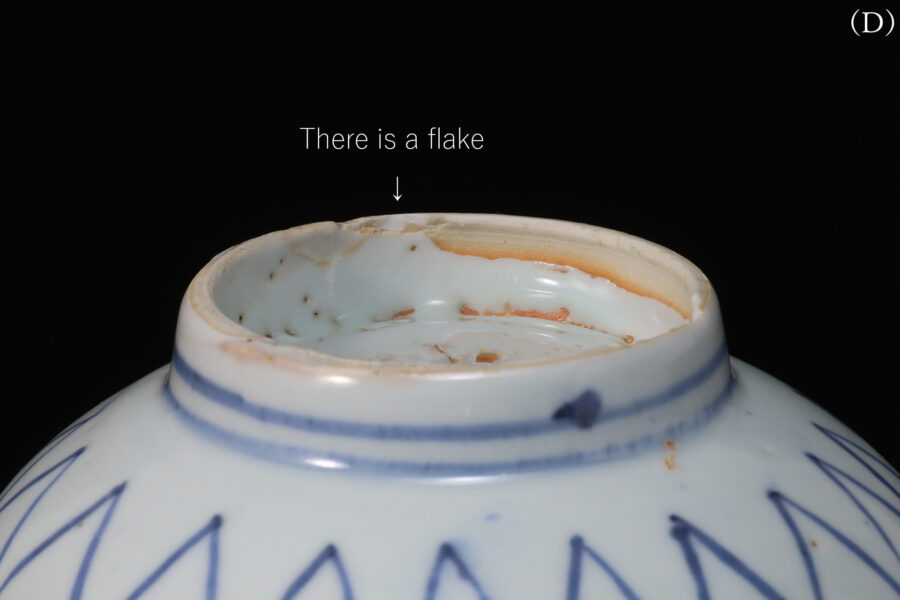

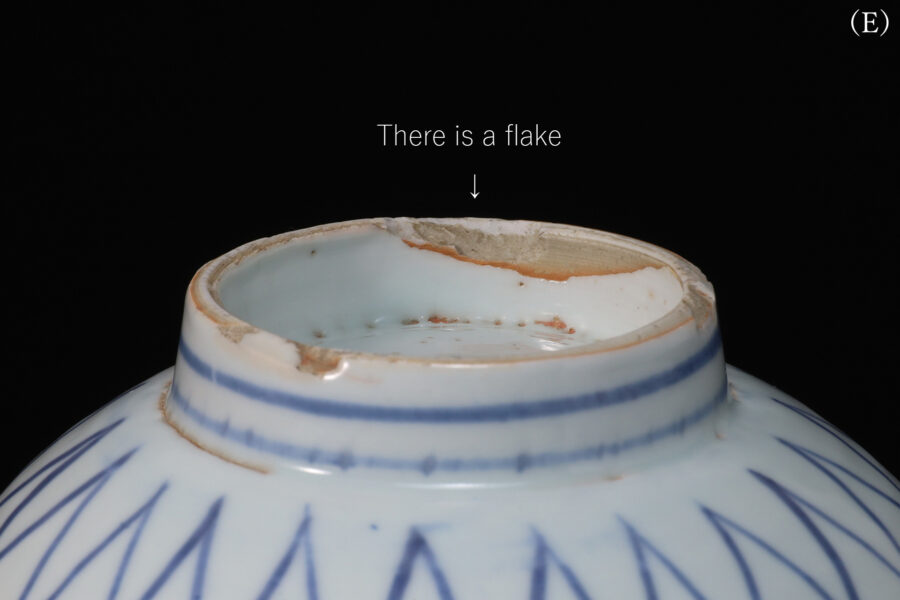

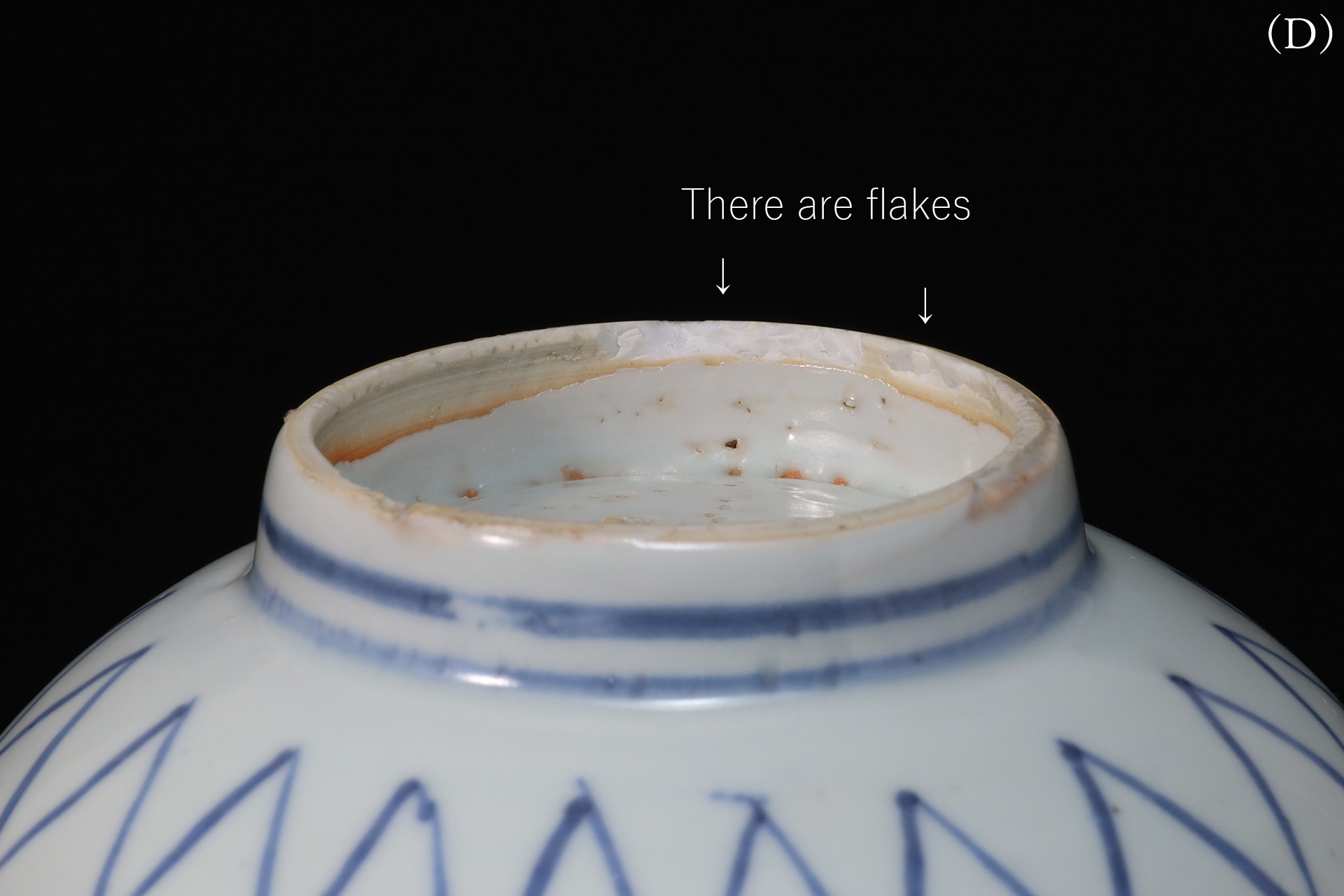

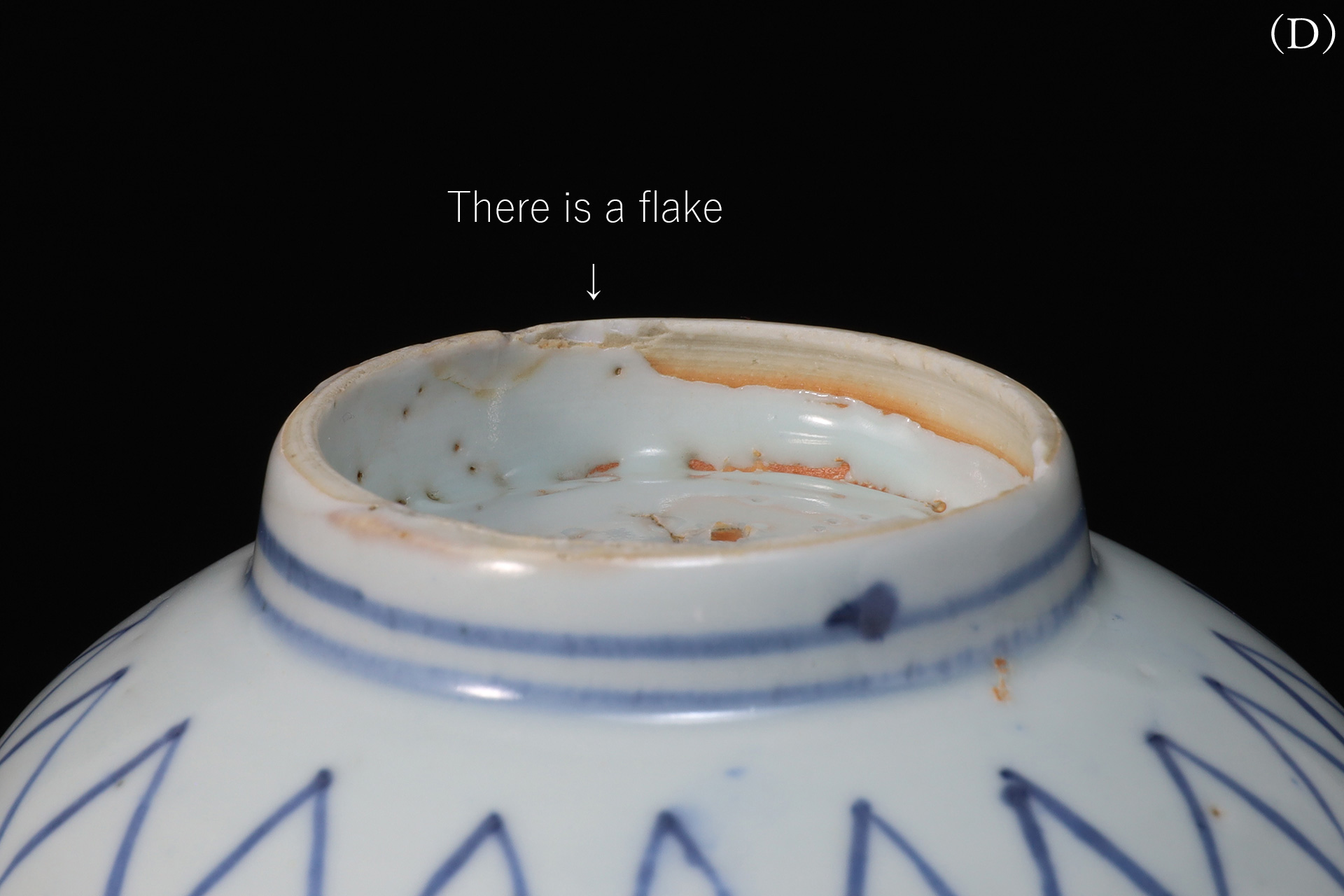

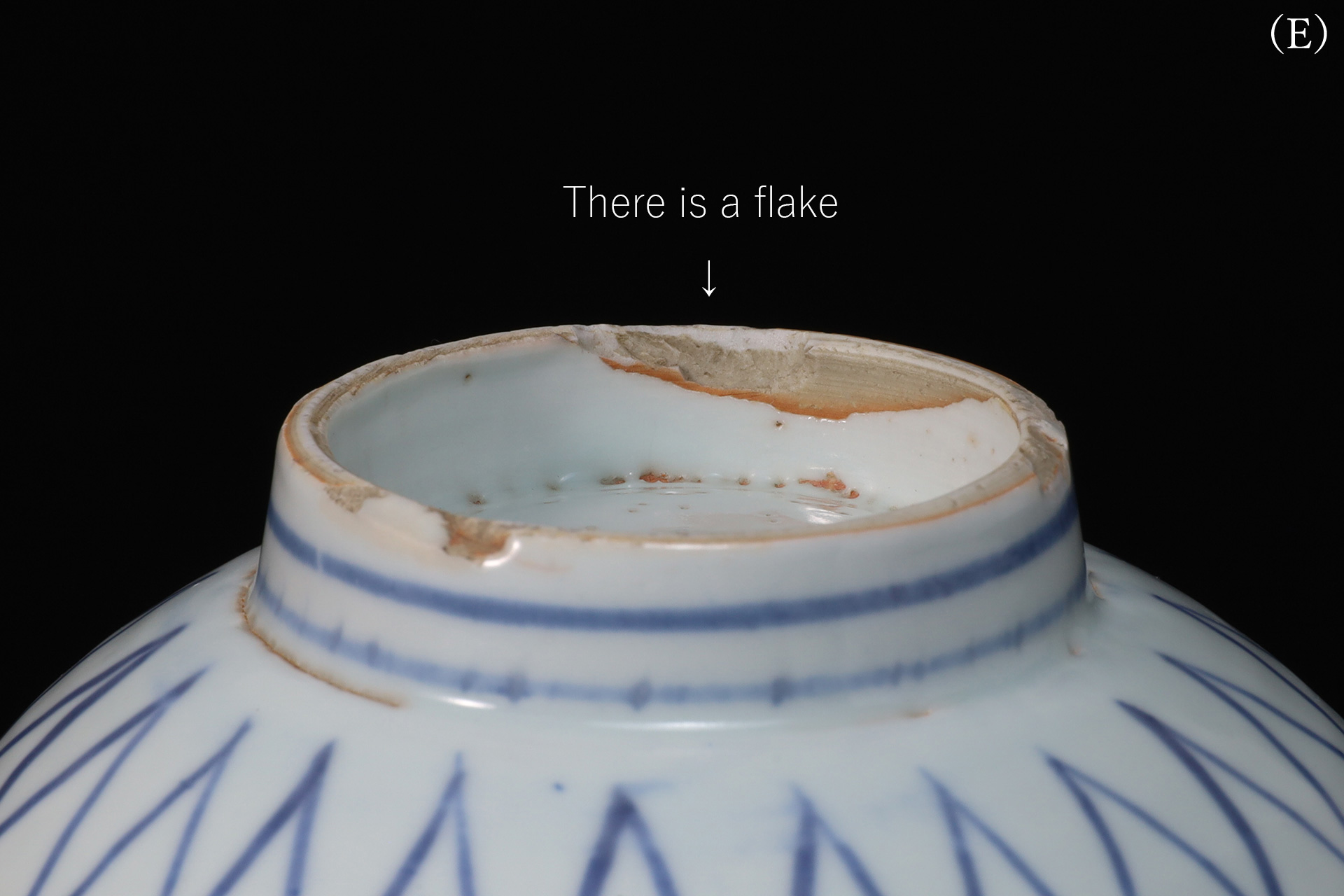

・1 bowl (D): There are three flakes on the base

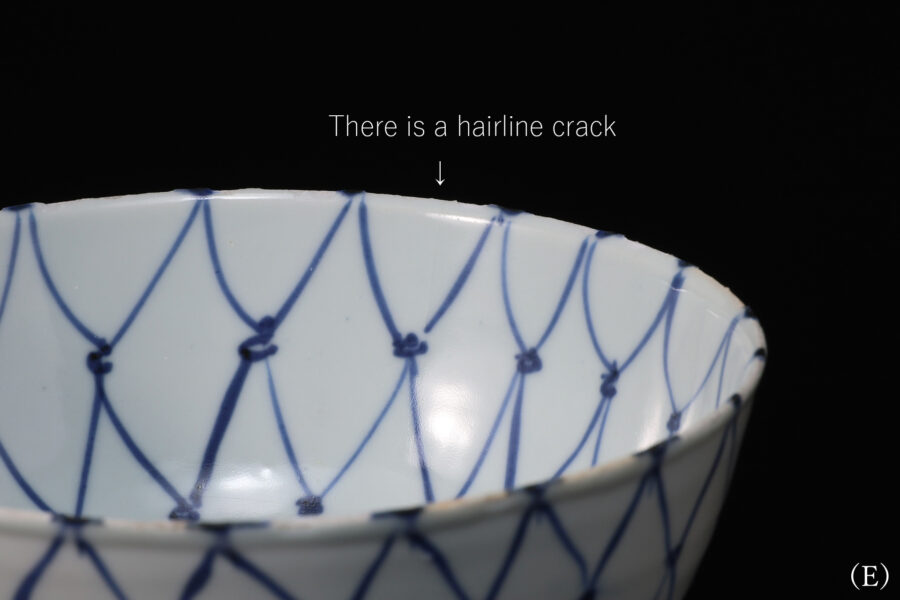

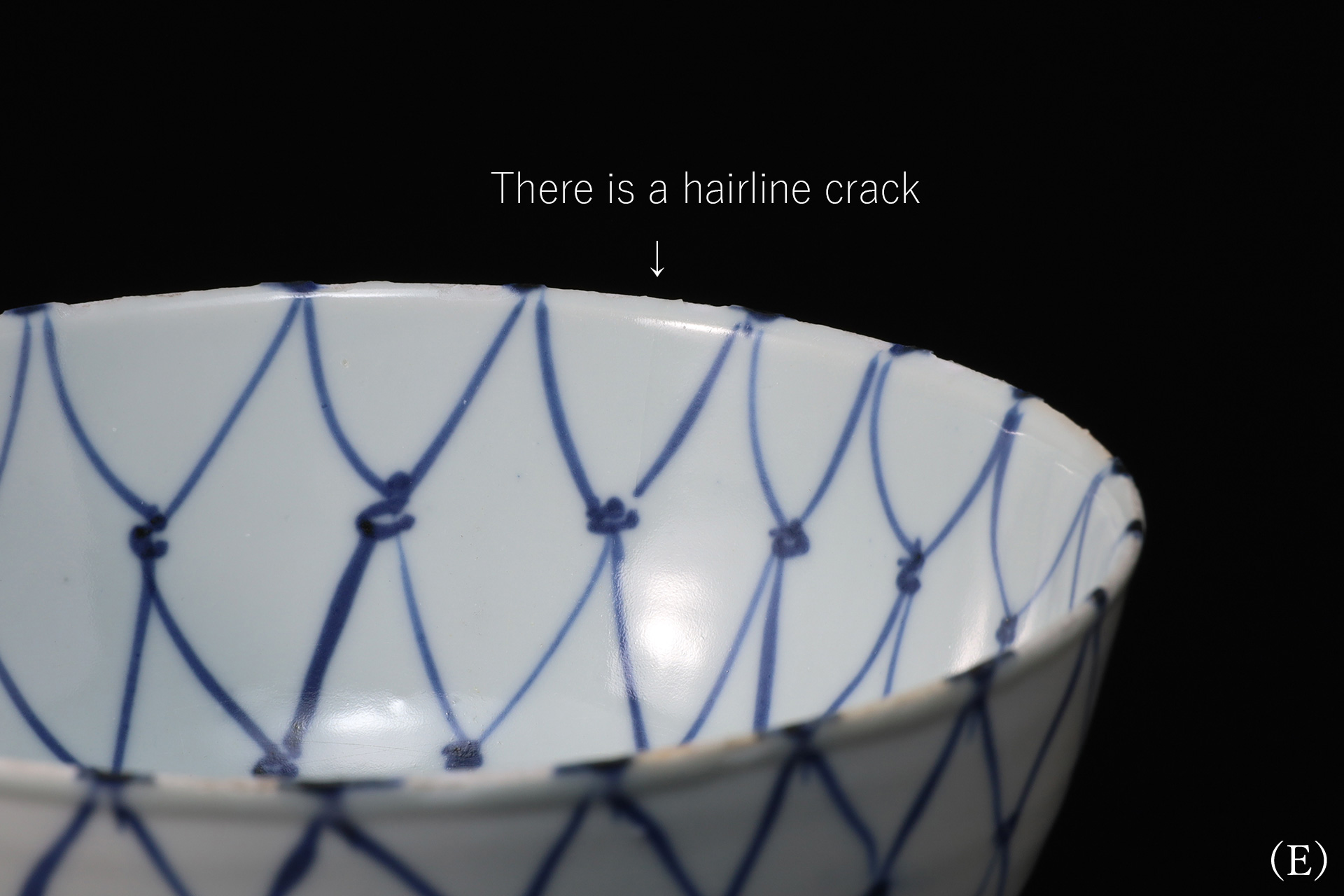

・1 bowl (E): There is a hairline crack on the rim and two flakes on the base

It possesses a beautiful surface, ideal cobalt-blue decoration, and an outstanding firing—fulfilling all the conditions of a superior work. There is a hairline crack on the rim, though it is scarcely visible to the naked eye. Slight flakes on the base is present, but it is unobtrusive and poses no concern.

Ko-Sometsuke

Ko-Sometsuke refers to a distinctive group of blue-and-white porcelain fired at the Jingdezhen kilns during the late Ming dynasty, particularly in the Tianqi era (1621–27). A distinct group of blue-and-white porcelains, known as Ko-Sometsuke, is cherished as a category of its own, characterized by unique stylistic features. In contrast to the Qing dynasty Shin-watari (New Imports), these works belong to the older tradition of Ko-watari (Old Imports), and many surviving examples were transmitted to Japan. Following the death of the Wanli Emperor, the Jingdezhen imperial kilns were shut down, and Jingdezhen private kilns assumed control over both production and distribution. Many potters who had once served in the imperial kilns moved to private kilns to sustain their livelihoods, leaving behind works that still reflect the refinement of official ware. A significant portion of these works are classified as Ko-Sometsuke and Shonzui. Ko-Sometsuke is broadly divided into two categories: tea pottery commissioned by Japanese tea masters, and everyday utensils for general use. As tea pottery, Ko-Sometsuke works were crafted in imitation of the thick-bodied forms favored by Japanese tastes, characterized by substantial walls and a bold, vigorous presence. In the late Ming dynasty, Japanese tea masters actively commissioned the production of novel tea utensils, seeking works that reflected their individual aesthetic sensibilities. Many Ko-Sometsuke works exhibit a phenomenon in which the glaze flakes away due to differences in shrinkage between the base and the glaze, exposing the underlying base. This effect, resembling insect bites, is poetically referred to as “Mushikui”. This phenomenon is most commonly observed along the rim and at the corner, where the glaze tends to be applied more thinly. Though typically regarded as a flaw in conventional ceramics, tea masters discerned in it a natural elegance, appreciating its rustic simplicity as a form of aesthetic expression.