This ko-sometsuke gourd-shaped bottle is the magnificent work with brilliant blue-and-white(sometsuke). This shape is often found in fuyode, but the actual work is a popular subject for flower and bird design. This was a special order from a japanese tea master and has continued to fascinate many people for approximately 400 years. It can be enjoyed in a wide variety of ways, such as a flower vase or a slightly larger sake bottle.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 250402-3

- Period

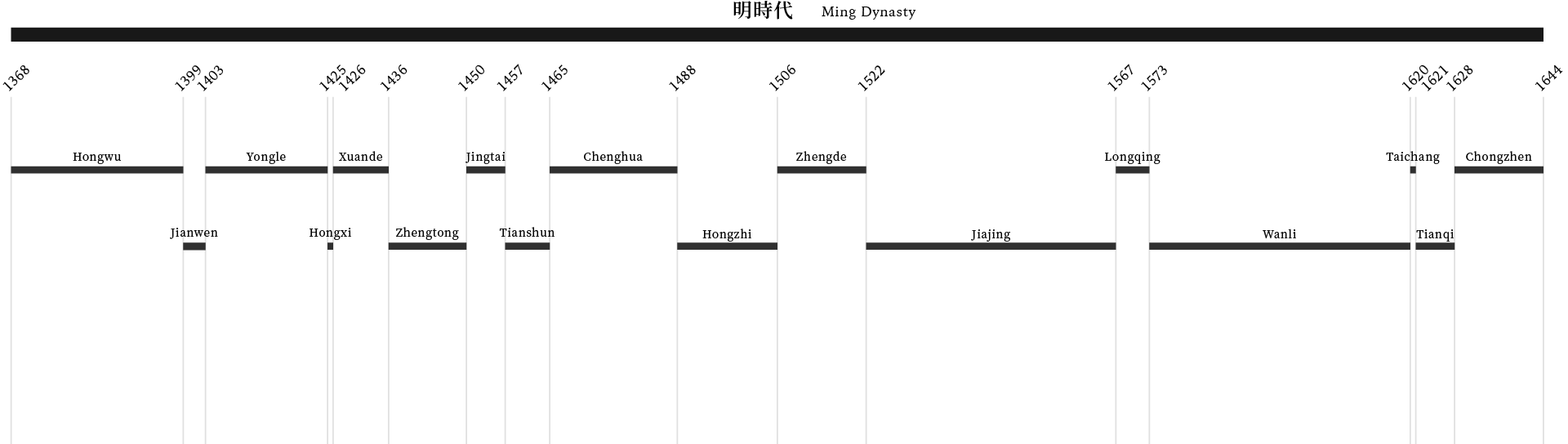

- Ming Dynasty

Early 17th century

- Weight

- 496g

- Body Diameter

- 10.4cm

- Top Diameter

- 2.8cm

- Height

- 22.0cm

- Bottom Diameter

- 6.8cm

- Description

- Paulownia Box

- Note

- The capacity is about 500ml for 80%

- Condition

- Excellent Condition(There is a mushikui at the edge)

It meets the requirements of the first class work with its strict shape, beautiful glaze, and good firing.

Ko-Sometsuke

Ko-Sometsuke refers to a distinctive group of blue-and-white porcelain fired at the Jingdezhen kiln during the late Ming Dynasty, particularly in the Tianqi Era(1621–27). A distinct group of blue-and-white porcelains, known as Ko-Sometsuke, is cherished as a category of its own, characterized by unique stylistic features. In contrast to the Qing Dynasty Shin-watari(New Imports), these works belong to the older tradition of Ko-watari(Old Imports), and many surviving examples were transmitted to Japan. Following the death of the Wanli Emperor, the Jingdezhen imperial kiln was shut down, and Jingdezhen private kiln assumed control over both production and distribution. Many potters who had once served in the Imperial kiln moved to Private kiln to sustain their livelihoods, leaving behind works that still reflect the refinement of official ware. A significant portion of these works are classified as Ko-Sometsuke and Shonzui. Ko-Sometsuke is broadly divided into two categories: tea pottery commissioned by Japanese tea masters, and everyday utensils for general use. As tea pottery, Ko-Sometsuke works were crafted in imitation of the thick-bodied forms favored by Japanese tastes, characterized by substantial walls and a bold, vigorous presence. In the late Ming Dynasty, Japanese tea masters actively commissioned the production of novel tea utensils, seeking works that reflected their individual aesthetic sensibilities. Many Ko-Sometsuke works exhibit a phenomenon in which the glaze flakes away due to differences in shrinkage between the base and the glaze, exposing the underlying base. This effect, resembling insect bites, is poetically referred to as “Mushikui”. This phenomenon is most commonly observed along the rim and at corner, where the glaze tends to be applied more thinly. Though typically regarded as a flaw in conventional ceramics, tea masters discerned in it a natural elegance, appreciating its rustic simplicity as a form of aesthetic expression.