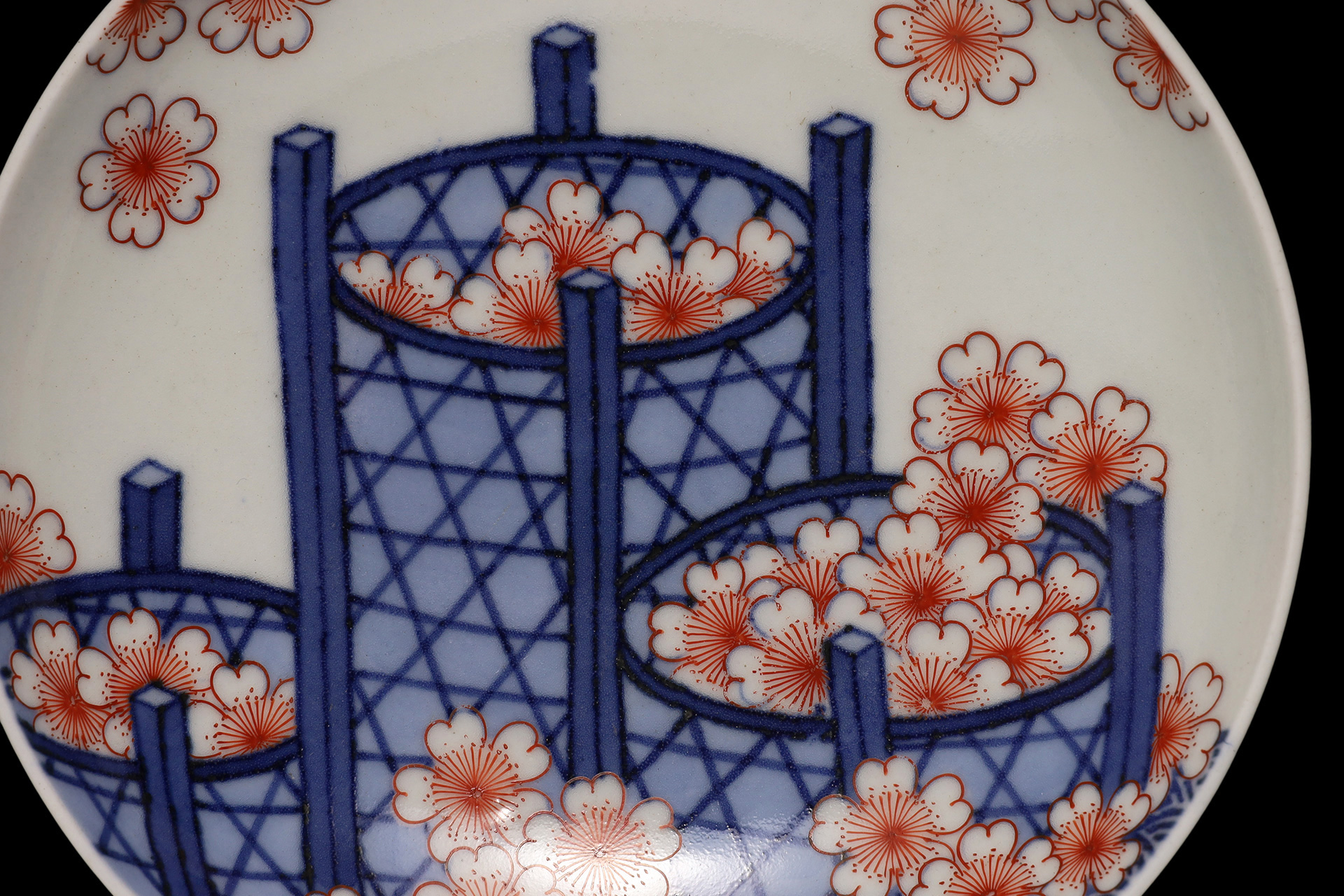

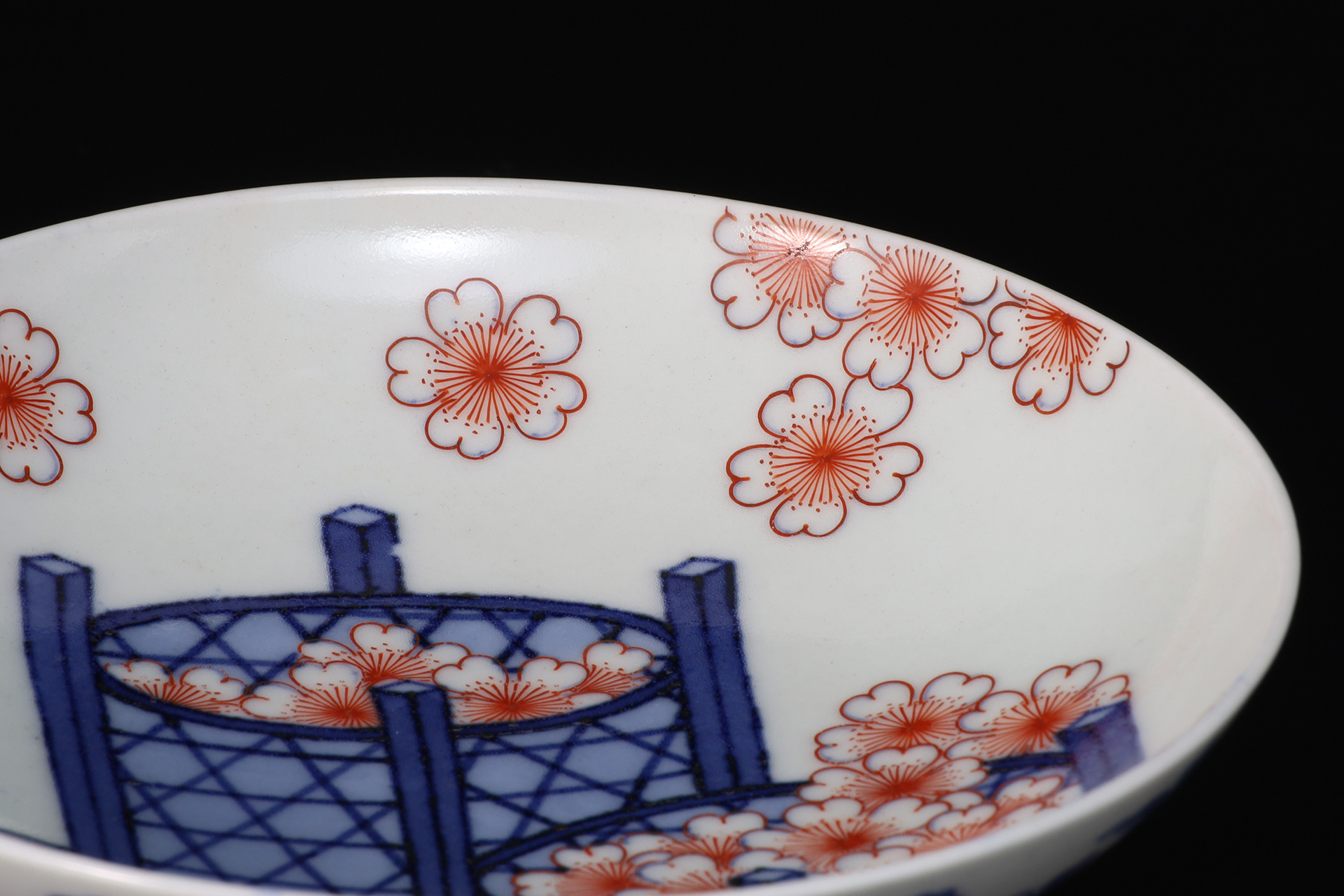

Nabeshima Small Dish with Cherry Blossoms and Flower Baskets Motif (Edo Period)

Sold Out

A distinguished example of Iro‑Nabeshima ware that reflects the splendor of the Genroku era (1688-1704). Centered on three flower baskets, the design of cherry blossoms dancing across the surface evokes the elegance and festive spirit of spring, imparting a refined sense of compositional beauty. The latticework of the baskets is rendered with masterful gradations of underglaze blue, while the wax‑resist seigaiha motif highlights the exceptional design sensibility characteristic of Nabeshima ware. On the reverse, a neatly executed karahana motif attests to the high quality of workmanship, embodying the clan kiln’s meticulous technique and aesthetic sophistication.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 250402-2

- Period

- Edo Period

End 17th Century - Early 18th Century

- Weight

- 206 g

- Mouth Diameter

- 15.0 cm

- Height

- 4.5 cm

- Base Diameter

- 8.1 cm

- Fittings

- Paulownia Box (Cloth‑Lined Type)

- Condition

- Intact

It fulfills the essential criteria of a first‑class work, with its refined form, beautiful glaze, and superb firing.

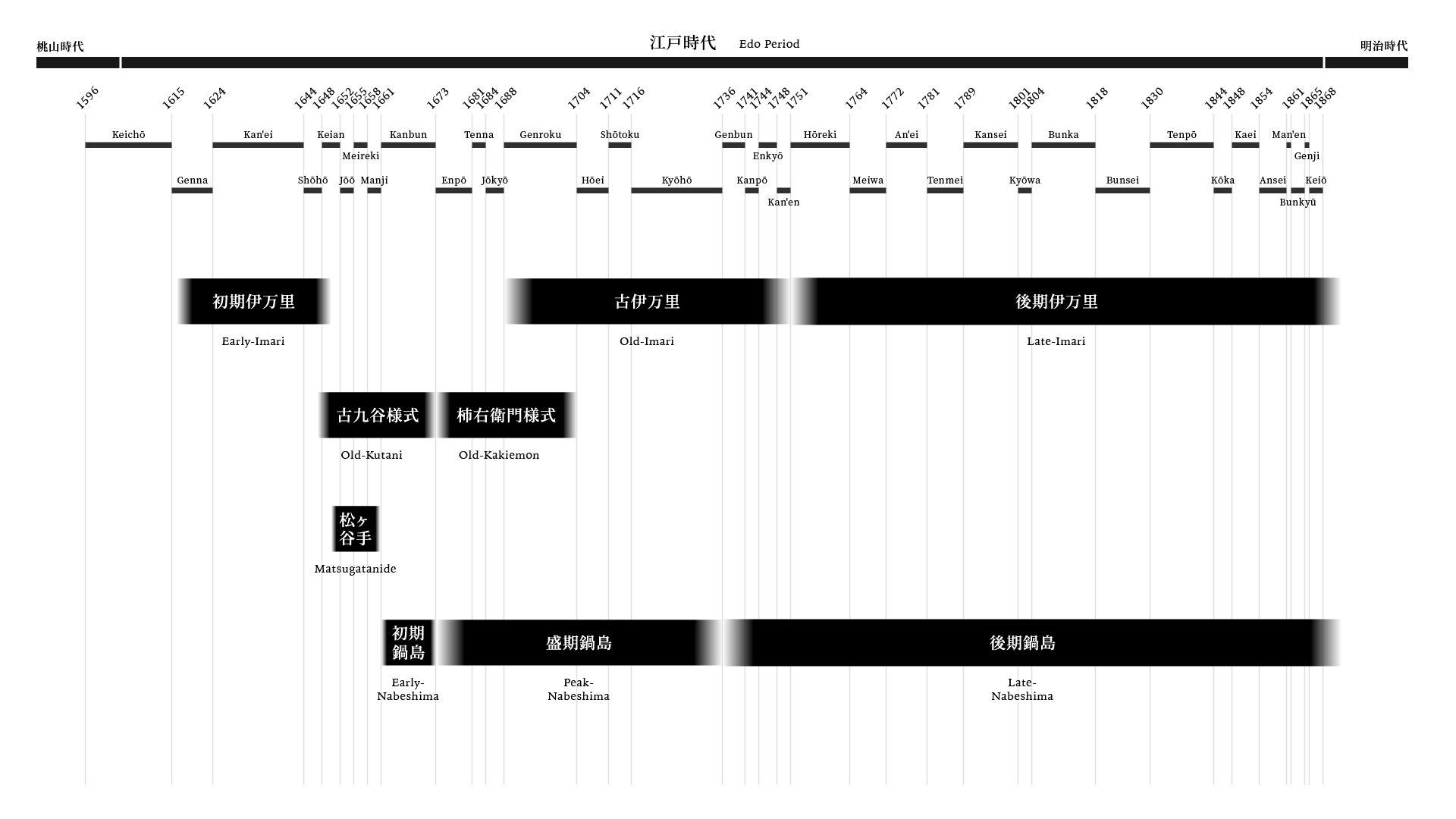

Nabeshima Ware

Nabeshima ware is a finely crafted and highly dignified porcelain specially commissioned and fired at the Nabeshima domain kilns in Okawachiyama, Matsuura District, under the patronage of the Nabeshima clan of the Saga Domain in Hizen Province. It is the only porcelain in Japan to possess the characteristics of an official kiln, and it stands as a world‑class masterpiece. Its technical refinement surpasses even the Kakiemon style, establishing an unparalleled reputation. The finest examples are often said to rival the imperial wares produced at China’s official kilns, a comparison that is by no means an exaggeration. Created as offerings to the shogunate—serving as proof of loyalty to the central authority of the bakuhan system—and presented to other feudal lords as symbols of amity, Nabeshima ware was never intended for commercial sale. Because production disregarded profitability entirely, these works were not distributed among the general public. The fundamental orientation of the domain kilns did not lie in tea ceramics but in practical vessels, especially dishes. In the Hizen region, ceramic‑producing areas were referred to as “yama,” and within the Nabeshima domain, the kiln dedicated to producing official wares was called the “Odogu-yama.” Selected master potters from various Hizen kilns were summoned to the Nabeshima kiln, where, in an isolated environment and under a strict organizational structure, a distinctive style was established. Records from the late Edo period note that 31 potters were employed, producing 5,031 pieces annually. A checkpoint was installed at the entrance to the kiln site, and passage by unauthorized individuals was strictly prohibited to prevent the leakage of secret techniques. Artisans working there were permitted to bear surnames and swords and were exempted from certain taxes. Production followed a division‑of‑labor system modeled after China’s official kilns, and even a single dish passed through the hands of numerous craftsmen. Offerings to the shogunate were produced with extras to account for breakage, and it is said that they were typically presented in sets of twenty. The early and mature periods saw the culmination of supreme techniques supported by exceptional craftsmanship. While works in underglaze blue and celadon exist, the most representative pieces are the “Iro‑Nabeshima” wares. Their method—drawing outlines in underglaze blue and applying overglaze enamels in red, green, and yellow—is considered to follow the “doucai” technique of the Chenghua era (1465–87) of the Ming dynasty, a level of refinement achievable only because the kiln operated without regard for cost. The designs shed Chinese and Korean influences, embodying instead a uniquely Japanese elegance. Motifs centered on plants of the natural world, along with landscapes, Noh costumes, and patterns drawn from Momoyama and Edo period painting manuals, crystallizing a beauty both graceful and noble. A representative vessel shape is the tall‑footed dish known as “wooden-cup form,” formed on the potter’s wheel. Compared with ordinary Arita folk kilns, the unusually tall foot is thought to have been intended to impart a sense of formality. Around the exterior of the foot, many works feature a distinctive underglaze blue pattern known as “comb-tooth pattern,” a technique permitted exclusively at the Nabeshima domain kilns and strictly forbidden elsewhere. Mature period works employ a meticulous method of shading (dami) within the underglaze blue outlines, but as time progressed, the lines gradually became less precise, eventually declining into simplified single‑line outlines. All products underwent rigorous inspection by multiple examiners, and only those that passed were delivered to the domain. Any defective pieces were completely destroyed. With the abolition of the feudal domains in 1871 (Meiji 4), the Nabeshima domain kilns were closed, bringing their distinguished history to an end.

https://tenpyodo.com/en/dictionaries/nabeshima/

Mature Period Nabeshima

The Mature Period Nabeshima refers to the porcelain produced at the Nabeshima domain kilns between the 1670s and the 1730s. In 1693 (Genroku 6), an official directive issued in the name of the second lord, Nabeshima Mitsushige, to the Arita Sarayama magistrate set forth a series of bold reforms. These included strict control over tribute wares and adherence to delivery deadlines; the creation of innovative porcelain by avoiding reliance on fixed, repetitive designs and by incorporating superior motifs from the private kilns of Wakiyama (Arita folk kilns); the prohibition of craftsmen from Wakiyama entering the domain kilns to prevent leakage of technical knowledge; the destruction of defective pieces within the kiln precincts; and the recruitment of highly skilled artisans from Wakiyama while dismissing those deemed incompetent. These measures triggered a major transformation in style. A close examination of the decorative motifs reveals many precedents in the Arita folk kilns. The comb‑tooth pattern with a fully painted footring can be traced to the Sarugawa kiln of the 1640s–50s, and the technique of bokashi‑dami (shaded overglaze coloring), perfected at the Kakiemon kiln and the Nangawarakamanotsuji kiln, appears in an even more refined form in Mature Period Nabeshima. Painting became increasingly pictorial in style, and techniques such as the introduction of the central negative‑reserve method were executed with remarkable precision. The period thus reached a pinnacle worthy of being called the apex of Japanese porcelain, distinguished by unparalleled technical mastery. Most of the representative iro‑Nabeshima pieces were produced during this era, and many large dishes—technically difficult to fire—were successfully made. The curves of the dishes maintain a beautifully balanced symmetry, while the reverse side typically features the prevailing combination of a comb‑tooth–patterned footring and a shippo‑musubi (linked seven‑treasures) design. In rare cases, gold decoration is also observed. According to records from the Kyoho era (1716–36), a total of eighty‑two items in five categories—large bowls (30.0 cm), large dishes (21.0 cm), medium dishes (15.0 cm), small dishes (9.0 cm), and choko cups—were presented to the shogunal household. The same number was delivered to the succeeding dainagon, and when combined with gifts to 35–41 senior officials of the shogunate, the total is said to have reached approximately 2,000 pieces.