Old Imari

古伊万里

Home > Fine Arts > Japanese Antique (To the Artworks Information Page)

Old Imari

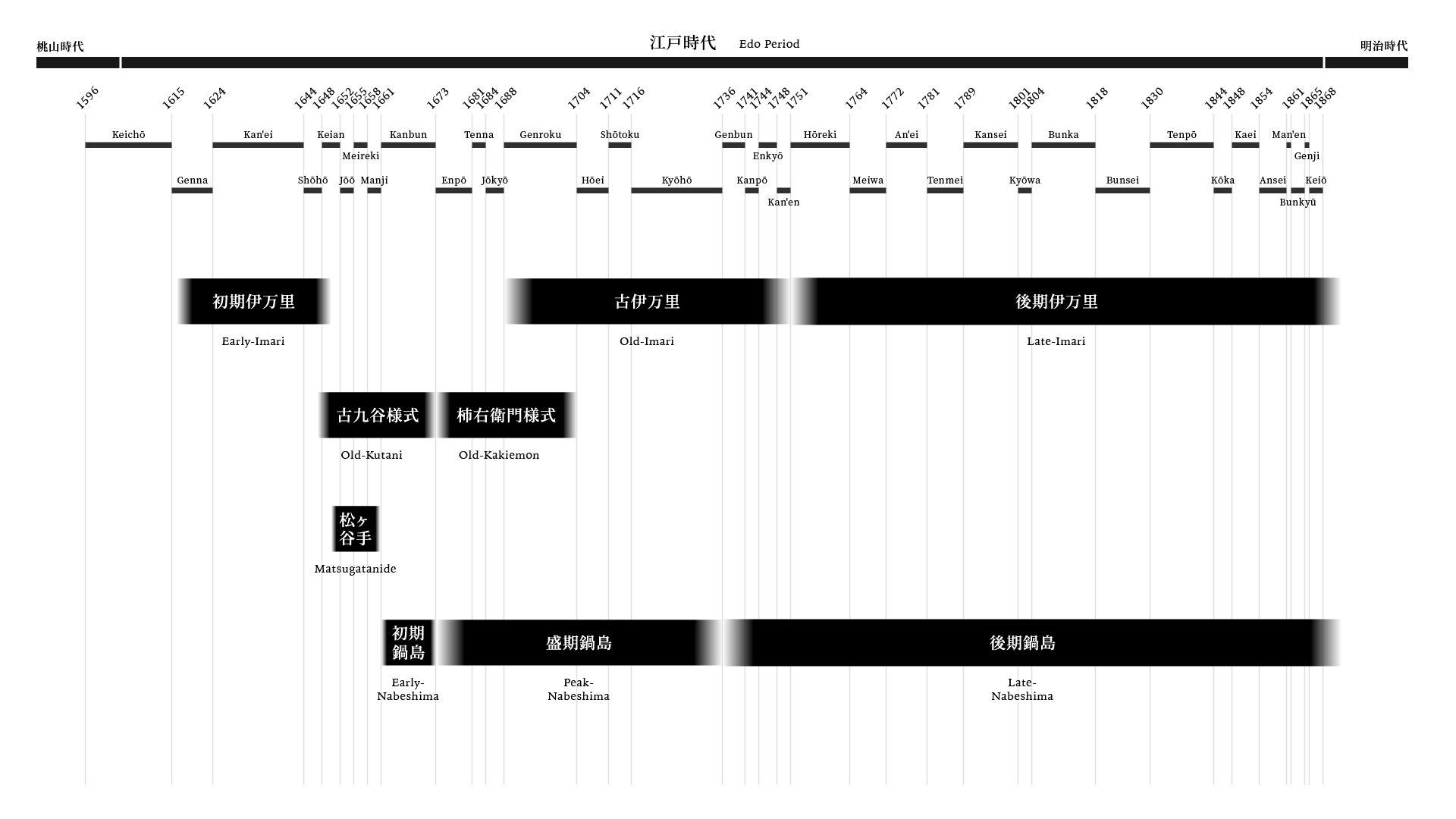

Old Imari is a collective term for porcelain fired in Arita, Hizen Province, during the mid-Edo period. While the domestic market favored dignified and well-balanced works—exemplified by Katamono (“masterwork that fits the mold of excellence”)—the core of production lay in export pieces, distinguished by elaborate designs that evoked exotic sensibilities. As Hizen porcelain came to be embraced by global markets as the finest alternative to Jingdezhen ware, a sophisticated division of labor among skilled artisans was established, enabling the high-quality mass production of ceramics. Among these, the opulent Kinrande style—featuring underglaze blue (sometsuke) layered with overglaze enamels and gilding—became emblematic of Old Imari, unfolding a world of elegant splendor that reflected the prosperity of the Genroku era (1688–1704). This decorative technique was perfected at the Jingdezhen kilns during the Jiajing reign of the Ming dynasty (1522–66), where gold leaf was fired onto porcelain surfaces to evoke a sense of opulence and refinement. In Europe, a vogue emerged among royalty and aristocrats for adorning palace interiors with porcelain, giving rise to the celebrated “Porcelain Rooms.” Porcelain came to be revered as a symbol of wealth and power. Old Imari wares that reached Europe were displayed not only as art objects on shelves and walls, but also served as elegant furnishings in reception spaces. As a result, many surviving pieces exhibit signs of age, such as wear to the overglaze enamels and gilding. Names such as “Old Imari,” “Old Japan,” and “Imari-yaki” remain beloved among collectors and connoisseurs both in Japan and abroad, attesting to the enduring reverence for Hizen porcelain.

Katamono

“Katamono” refers to a distinguished group of Old Imari made for domestic use, characterized by rich coloration and Kinrande-style decoration. The term implies a “masterwork that fits the mold of excellence,” and pieces of comparable quality are sometimes referred to as jun-gata (“semi-katamono”). Notably, the term “Katamono” does not appear in Edo period documents and is believed to have become established in the Meiji period. Katamono stands apart from the mass-produced export Imari ware made for European markets. Instead, it fulfilled the refined demands of feudal lords and wealthy merchants, representing the highest echelon of Old Imari enamel decoration. Although not originally intended as offerings to the shogunate or regional domains, their exceptional quality earned them the honorary title kenjō-de (“presentation-grade pieces”). The designs are meticulously rendered and imbued with auspicious and narrative motifs, including red roundels with dragons, stormy seas (araiso), the immortal Kinkō riding a carp, five sailing ships, the character for longevity (kotobuki), treasure motifs (takara-zukushi), princess dishes (hime-zara), and ceremonial arrows (yumi-hama). The forms are equally diverse, encompassing round bowls, helmet-shaped bowls (kabuto-bachi), spinning-top-shaped bowls (koma-gata bachi), and flat bowls. Katamono pieces were treasured as confectionery bowls for tea gatherings, celebratory gifts, and vessels for formal banquets. Even after reaching their peak during the Genroku era (1688–1704), they continued to be produced as a major category of Imari ware. However, their quality gradually declined with the passage of time.

Fuyode

Fuyode is a style of blue and white porcelain developed in the jingdezhen kiln in china during the Wanli era(1573-1620). The name “Fuyode” is said to come from the fact that the large circular opening in the center of the porcelain vessel, surrounded by petal like sections, is reminiscent of the petals of a cotton rose hibiscus. The fuyode is a representative design of chinese porcelain made in response to the demands of southeast asia, the orient, and europe, and was produced mainly during the tianqi and the Chongzhen era(1621-44)in the late ming dynasty. Fuyode is mainly in the shape of dish vessels, but some have kundika and bottle like forms. Civil unrest and restrictive policies on overseas trade following the change of the ming dynasty to the qing dynasty in the 1640s resulted in a decline in the quality of jingdezhen kiln and other porcelain kilns, making it almost impossible to purchase porcelain from china. As a result, a stable supply of japanese porcelain became the alternative, and japan entered the era of a glamorous export industry. Chinese porcelain samples, in possession of the director of the dutch trading house, accompanied each order. The potters in hizen are thought to have faithfully reproduced the samples. Fuyode led to a significant stylistic shift in imari ware and took a prominent position in blue and white porcelain for export. The fuyode dish with the dutch east india company’s VOC emblem was called the “Company Plate” and was personally used by the governor of batavia as well as by various trading houses.

Agarwood Jar

The term “Jinko Tsubo(Agarwood Jar)” mainly refers to imari ware jar with wide mouthed lid. Originally the name of jar for storing jinko(agarwood), a type of aromatic wood, jinko tsubo now refers simply to the shape of the vessel. In china, the shape is said to have been developed in jingdezhen kiln of the yuan dynasty. It became a standard form of jar throughout the ming and qing dynasties. Following the chinese models, hizen arita also mass produced them as the highlight of exported classic imari ware, gaining high popularity in europe. Some of these works had metalworking done in europe and were used as lamps.

Shaving Basin

The higezara(shaving basin)was a dish used for shaving and washing one’s beard, with part of the wide mouth rim cut off in a semi circle shape. Shaving basin were also popular as decorative wall dishes, with strings threaded through the two small holes in the top. It was highly popular as typical exported old-imari ware because of its unique vessel shape and diverse designs.

The Era Establishing the Export Industry Between the VOC and Japan

The east india companies were chartered companies established by european countries in the 17th century(the british in 1600, the dutch in 1602, and the french in 1604)for trade with the orient. The dutch east india company’s monogram, consisting of the initials “VOC”(Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie), was its emblem, was put on warehouses, coins, cannons, flags, ceramics, etc, to indicate the company’s ownership of products. In addition to spices, its original product of interest, the company also sought porcelain that could not be produced in europe and traded with china. The hard porcelain imported from china was called “White Gold” and was traded as a valuable item, rivaling gold in value. Once vast quantities of porcelain, a luxury item and symbol of wealth, were brought to europe, its beauty deeply impressed europeans, encouraging china to produce even more products. However, due to the civil war following the change between the ming and qing dynasties in the 1640s and policies restricting overseas trade, the quality of porcelain fired in the jingdezhen kiln and other porcelain kilns became inferior, making it almost impossible to buy porcelain products. As a result, the company sought japanese porcelain, which could be produced without interruption, as an alternative. In 1653, japan entered into an export deal with the dutch east india company(VOC)for imari ware. In 1659, japan received a massive order of about 56,700 pieces, ushering in a glamorous era for the export industry in japan. The new feudal system of the tokugawa government beginning to take shape, imari ware was thrust into the limelight of the international market as a product of the nabeshima clan of the saga domain. Because europe demanded identical replacements for chinese porcelain, many early pieces exported imitated the fuyode style and other styles from the late ming dynasty. The large volume of orders from the VOC led to significant technical advances at the hizen arita kilns, and the expanded capacity of these kilns made it possible to produce many jinko tsubo(agarwood jar). The exported porcelains varied widely in shape. Even considering this, it is clear that the expansion of trade with the VOC contributed to the significant flourishing of imari ware. When the qing dynasty lifted the qian-jie-ling(order blocking maritime traffic and trade)in 1684, exports of chinese porcelain resumed, and from around 1712, exports boomed. Chinese porcelain once again regained its dominant position in the market. As a result, imari ware lost out in market competition with chinese porcelain, which boasted quality, quantity, and low prices. China overwhelmingly outnumbered japan in the total number of porcelain exported through trade with the VOC. The establishment of meissen, the first porcelain kiln in europe, in 1710 contributed to the gradual decline of porcelain exports from asia. The official japanese porcelain trade ended in 1757 with a mere 300 pieces and then was left to private trade by the trading houses.

Events Related to the VOC

- 1602(Keicho7):Establishment of the dutch east india company(VOC).

- 1609(Keicho14):Establishment of the dutch trading post in hirado.

- 1641(Kanei18):Relocation of the dutch trading post to dejima, nagasaki.

- 1644(Kanei21):End of porcelain exports from china to the VOC, following a decline in porcelain exports beginning in about 1640.

- 1650(Keian3):Beginning of export of porcelain from japan as a replacement for chinese porcelain.

- 1651(Keian4):Beginning of exports to chinese merchants in addition to dutch merchants, where imari ware was acquired by the dutch and chinese alike.

- 1653(Shoo2):Signing of export agreement with VOC for imari ware, beginning their export. Records remain of these trades.

- 1659(Manji2):Beginning of full scale export of blue and white porcelains, including fuyoude, etc., after receiving a large order(approx. 56,700 pieces)of imari ware from the VOC.

- 1661(Kanbun1):Prohibition of chinese porcelain exports in the qing dynasty following the qian-jie-ling proclamation.

- 1684(Jokyo1):Resumption of exports of chinese porcelain after the lifting of the qian-jie-ling proclamation.

- 1710(Hoei7):Establishment of a porcelain factory in meissen, germany.

- The Shotoku era(1711-16):Tightening of restrictions on foreign trade, leading to a halving of the number of dutch and chinese ships arriving at dejima. Thus, porcelain exports also began to decline.

- 1725(Kyoho10):Stagnation of trade between japan and the VOC.

- 1757(Horeki7):End of official porcelain trade after only 300 pieces according to the VOC records, thereafter relegated to private trade by the trading houses.

- 1799(Kansei10):Dissolution of the VOC.

Shift to Meet Domestic Demand Late-Imari

Imari ware was widely shipped to various regions in japan to meet demand, in addition to overseas trade. Domestic demand grew because wealthy merchants began to decorate their homes not only with makie and other lacquerware but also with imari ware. After the official porcelain trade with the dutch east india company(VOC)ended in 1757, imari ware became more of a general furnishing(tableware)than a decorative piece of fine art and gradually became popular among the middle class, including the townspeople. With techniques to divide labor already in place, porcelain production inevitably moved toward mass production for the domestic market. As a result, shapes became crude and lost their elegance. Furthermore, a typhoon in august 1828 caused a major fire in hizen arita. Production and product quality declined significantly, leading some craftsmen to move to other ceramic production areas or even change occupations. Combined with the rapid development of porcelain production in various regions, especially in the seto region, the imari ware production suffered a fatal blow from internal factors such as its weakening infrastructure and external factors such as fierce competition. In 1841, with permission from the head of the saga clan to revitalize the area, Mr. Yojibee Hisatomi, a wealthy arita merchant, resumed trade with the netherlands under the brand “Zoshuntei”. In the breath of the new era at the end of the edo period, the lives and culture of ordinary people became vibrant, and spring and autumn festivals, fairs, weddings, funerals, and ceremonies at shrines and temples were very much in vogue. Records tell us that drinking and feasting at festivals were incredibly extravagant. Because festivals attracted large numbers of ordinary people, there was an increased need for larger dishes to serve sake and snacks. As a result, orders for larger dishes increased on a national scale. Local cuisine sawachi cuisine, representative of tosa province(now kochi prefecture), is a typical example of dishes that use larger dish. Among these late-imari works, which mainly focus on everyday items, the remarkable pieces featuring exotic dutch people, sumo wrestlers, the fifty three stations of the tokaido, and maps of japan have received high praise for their fascinating design compositions.

We sell and purchase Old Imari

We have a physical shop in Hakata-ku, Fukuoka City, where we sell and purchase "Old Imari" works. Drawing on a long career and rich experience in dealing, we promise to provide the finest service in the best interests of our customers. With the main goal of pleasing our customers, we will serve you with the utmost sincerity and responsibility until we close the deal.