Ko-Karatsu

古唐津

Home > Fine Arts > Japanese Antique (To the Artworks Information Page)

Ko-Karatsu

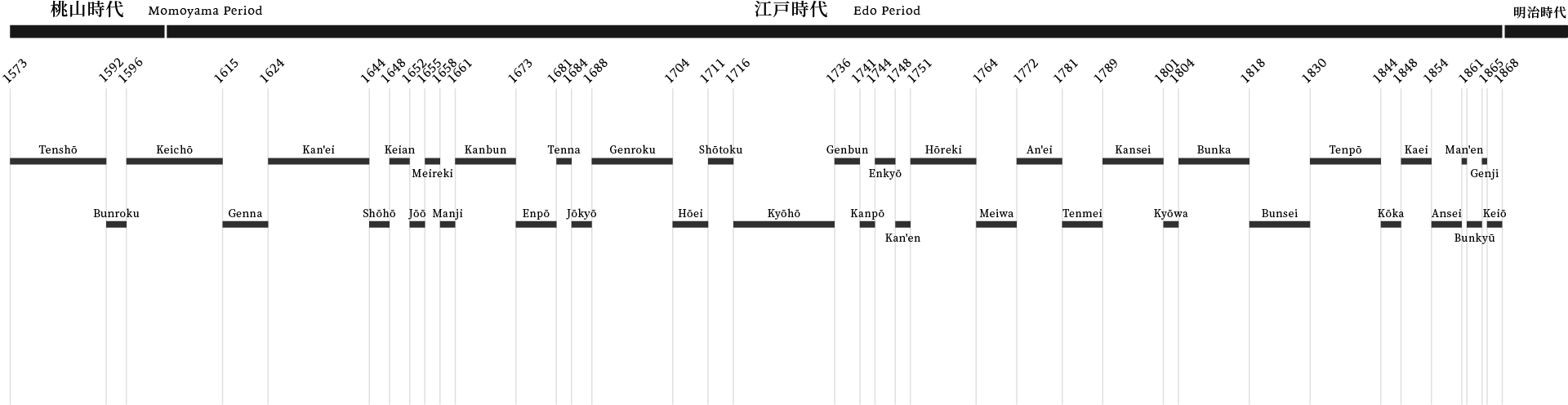

Karatsu ware refers to the pottery produced in the Hizen region, particularly within the Karatsu Domain of Hizen Province. Its name derives from the fact that these wares were shipped out from the port of Karatsu. Highly esteemed as tea ceramics, Karatsu ware has long been cherished by tea practitioners, to the extent that it is celebrated in the phrase, “First Raku, second Hagi, third Karatsu.” Its origins trace back to the late 16th century in the Kitahata area of Karatsu City in northern Saga Prefecture. It is said that Hata Chikashi, Mikawa-no-Kami, lord of Kishidake Castle, invited potters from the Korean Peninsula to establish kilns, and numerous early kiln sites from this formative period remain scattered around the castle town. When the Hata clan was dispossessed in 1593 (Bunroku 2) after incurring the displeasure of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the potters dispersed throughout Hizen—a historical event known as the “Kishidake Kuzure.” Shortly thereafter, Terasawa Hirotaka, Shima-no-Kami entered the domain, marking the establishment of the Karatsu Domain. This dispossession and the subsequent abandonment of the kilns serve as important evidence that Karatsu ware was already being produced before 1593, that is, during the Tensho era (1573–92). The techniques brought by Korean potters during the Bunroku–Keicho invasions (1592–98) further supported the flourishing of Karatsu ware from the Momoyama period into the early Edo period. During Hideyoshi’s encampment at Nagoya Castle, Furuta Oribe is said to have stayed in the region for about a year and a half from 1592 (Bunroku 1), providing guidance to the various Karatsu kilns. Moreover, the multi‑chamber climbing kiln (renbo‑shiki noborigama) was transmitted from Karatsu to Mino, where it was constructed at the Kujiri Motoyashiki site. The influence of Korean ceramic technology on Japanese kiln culture was profound and far‑reaching. The name “Karatsu ware” first appears in the Oribe Tea Gathering Records (Oribe chakai‑ki) of 1602 (Keicho 7) as “Karatsu‑yaki dish,” and it is frequently mentioned throughout the Keicho era (1596–1615). By the mid‑17th century, the term “Ko‑Karatsu” (“Old Karatsu”) also appears, indicating that its historical value was already recognized at that time. Although much of Karatsu ware was mass‑produced for everyday use, the popularity of tea preparation from the Momoyama to early Edo periods brought these wares to the attention of tea connoisseurs, who began to appreciate them as tea ceramics. Some pieces were even made to order for tea masters, and such works are highly valued today for their rarity. In the 17th century, the discovery of porcelain stone at Izumiyama by the immigrant potter Yi Sam‑pyeong (Japanese name: Kanagae Sanbei) and his success in porcelain production brought a major turning point to Karatsu ware. The rise of Imari ware led to the decline of Karatsu ware; although distinctive styles such as Mishima‑Karatsu and Nisai‑Karatsu emerged in the early Edo period, they could not rival the appeal of Ko‑Karatsu. Thereafter, only the official kilns (the “O‑chawan‑gama”) continued in limited operation. In the early Showa period, research by scholars such as Kanehara Tohen (1897–1951), Mizumachi Wasaburo (1890–1979), and Furutachi Kuichi (1874–1949) advanced significantly, and tens of thousands of ceramic shards were excavated from old kiln sites throughout the Hizen region. With its unadorned clay texture and warm, nostalgic hues, Karatsu ware embodies a sense of brightness and vitality. It stands as a true expression of the essence of Japanese ceramic art—an art born from the union of earth and flame.

Eighty Percent by the Artisan, Twenty Percent by the User

Karatsu ware gently absorbs tea stains and moisture over time, deepening its surface landscape and cultivating a quietly refined presence. As the saying goes, “Eighty percent by the artisan, twenty percent by the user,” these vessels mature through use, and sharing in that gradual evolution is one of their true pleasures. Pieces that are lightly fired, with glazes that have not fully melted, reveal this tendency even more distinctly, and features such as amamori—the subtle traces of seepage—grow into accents that heighten the vessel’s character.

斑唐津

斑唐津とは失透性の藁灰釉が施された唐津焼です。

白濁した釉薬が変化に富んだ斑状になり、

古唐津の中でも最も古い岸岳系の窯で多用された技法として知られています。

還元焼成では乳白色の中に青みが差した物も見られ、

酸化焼成では黄ばんだ風合いとなります。

酒を注ぐと見込みが美しく映え、

中でも「斑唐津の筒盃」は酒盃の王者に相応しい貫禄を示しています。

瀬戸唐津

瀬戸唐津とは長石釉が施された瀬戸風の古唐津です。

高麗茶碗の影響下に茶陶として生まれた事を示す雅味に富んだ作品が多く、「本手」と「皮鯨手」の二種に分類されます。

本手は砂気の多い白土に縮緬皺が出て、

灰白色や枇杷色を呈した長石釉に粗めの貫入が不規則に入り、豪快な梅花皮も見られます。

青井戸、蕎麦、熊川、呉器等の形があり、見込みの鏡に3~4つの目跡が残ります。

飯洞甕、帆柱、道納屋谷窯等から類似した陶片が出土しており、

阿房谷、道園、椎の峰窯等においても焼成されたと推測されています。

抹茶碗だけでなく、長崎県各所の消費地から瀬戸唐津の陶片が確認されており、

小碗、小鉢、皿等もあり、黒い油染みが残った灯明皿として使用された作例もあります。

皮鯨手は蕎麦形の本手瀬戸唐津を写したとされる平茶碗で、

鉄釉が施された口縁が鯨の皮身のように見える事によります。

見込みの鏡に3つの目跡が残り、高台内に兜布が見られます。

圧倒的に数が少ない事からも茶陶としての小規模生産だったと推測されます。

この二種は窯も時代も異なるものと推定され、茶家の間では本手の方が古いと伝えられます。

Ko-Karatsu and Mino Ware

Many similarities in vessel forms and decorative styles can be observed between Ko‑Karatsu ware and Mino ware. During the Bunroku campaign, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi encamped at Nagoya Castle, Furuta Oribe is said to have stayed in the region for about a year and a half from 1592 (Bunroku 1). After the fall of the Hata clan, Terasawa Hirotaka, Shima‑no‑Kami, became the lord of the newly established Karatsu Domain. As he was both a fellow disciple of Oribe in the tea tradition and originally from Mino, their relationship is believed to have been particularly close. Against this background, some scholars have suggested that Oribe may have provided guidance to the kilns in the Karatsu region. However, it is more plausible that the influence stemmed not from Oribe’s direct instruction but rather from the broader impact of Mino ceramic traditions. Among the kilns known for producing kutsu‑chawan (distorted tea bowl) in Karatsu are the Kameya-no-Tani kiln (Matsuura‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Okawabaru kiln (Matsuura‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Koraidani kiln (Taku‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Uchida-Saraya kiln (Takeo‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Ushiishi kiln (Hirado‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Shokodani kiln (Hirado‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), and Rishokoba kiln (Hirado‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu). It is believed that Kato Kagenobu visited many of these principal kilns. It is also noteworthy that the multi‑chamber climbing kiln (renbo‑shiki noborigama) was transmitted from Karatsu to Mino, where it was constructed at the Kujiri Motoyashiki site. The influence of Korean ceramic technology introduced to Japan during this period was profound and transformative for the development of Japanese kiln culture.

奥高麗

奥高麗は古唐津の一種で最も声価が高い大振りの茶碗であり、

井戸茶碗に並ぶとまで評されています。

高麗(朝鮮半島)の奥で焼成された物、高麗の奥から渡ってきた陶工が焼成した物等、

名称については様々な諸説がありますが、

高麗茶碗に似たところから名付けられたとするのが穏当です。

「奥高麗」という名称は江戸中期以前の茶会記には確認する事ができません。

雑器からの転用とは考え難いという見解もあり、

熊川や井戸等の高麗茶碗を手本に茶碗として焼成された物と推測されています。

市ノ瀬高麗神窯、甕屋の谷窯、道園窯、藤の川内窯、阿房谷窯、焼山窯、椎の峰窯、

川古窯の谷新窯、大草野窯、葭の元窯等で焼成されたと考えられています。

Chosen-Garatsu

Chosen-garatsu is a type of karatsu ware that combines an iron glaze with a devitrifying straw ash glaze. The area where the iron glaze and straw ash glaze blend together creates an exquisite sea cucumber glaze, which continues to fascinate many collectors and japanese tea masters. Due to the clay’s high iron content, the base takes on a deep reddish brown color when fired in an oxidizing flame. Generally, three dimensional objects are made by placing a disk of clay as the base and then forming clay strings into rings(coils) and stacking them on top of each other in layers. Once it has reached the appropriate height, a backing board is placed inside and the outside is evenly struck up and down, left and right with a racket shaped hammer, stretching it out. This causes the rings to adhere tightly to each other, making the vessel wall thin and bulging, resulting in a light and strong vessel. The engravings, such as diagonal line design, lattice design, and blue ocean wave design, are a device to prevent the board from sticking to the base, and while they shape the vessel, they also create a kind of secondary decoration inside. Finally, the edge is smoothed on a potter’s wheel and the bottom is carved to finish it off. Some works are made without hammering, simply smoothing the surface on a potter’s wheel, but these works are heavy. The bottom is marked with shell marks or covered with rice husks to prevent sticking. The matsuura style old-karatsu fujinokawachi kiln(kayanotani kiln) is known as the most famous kiln.

We sell and purchase Ko-Karatsu

We have a physical shop in Hakata-ku, Fukuoka City, where we sell and purchase "Ko-Karatsu" works. Drawing on a long career and rich experience in dealing, we promise to provide the finest service in the best interests of our customers. With the main goal of pleasing our customers, we will serve you with the utmost sincerity and responsibility until we close the deal.