Damage / Restoration

傷 / 美術修復

Perspectives on Damage and Restoration in Works of Art

The term “artwork” encompasses an exceptionally broad range—from centuries‑old antiques to modern and contemporary crafts, including works by living artists. From the standpoint of asset value, damage or restoration is generally viewed unfavorably in the field of modern and contemporary craft. In the world of antiques, however, ceramics tend to be regarded with relative tolerance, whereas porcelain is more strictly subject to devaluation. That said, even porcelain may inevitably exhibit minor flaws when the piece is of great rarity. Naturally, nothing surpasses a first‑rate, completely intact example. Yet, as the saying “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” suggests, becoming overly sensitive to imperfections can narrow the scope of one’s collecting. Maintaining a broad perspective and choosing works that genuinely resonate with your own sensibilities is, I believe, the true foundation of a rich and fulfilling collection.

On Art Restoration

Anything with a physical form inevitably carries the risk of damage. The circumstances vary widely—from highly rare works of art, to objects imbued with family memories, to one‑of‑a‑kind pieces that exist nowhere else. In recent years, tomonaoshi (restoration that matches the original surface) has become so refined that it is nearly impossible to detect with the naked eye. Beyond this, there are many other restoration techniques employing gold, silver, maki‑e, lacquer, and more. Such restoration practices do more than simply return an object to its proper shape. They are meaningful acts that preserve the sentiments invested in the piece and carry them forward into the future.

Basic Terms for Describing the Condition of Artworks

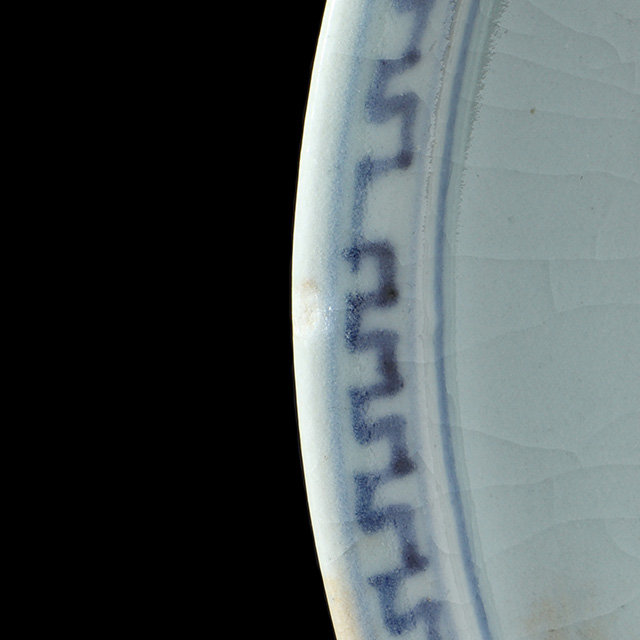

Crazing (Kannyu)

This term refers to the fine network of cracks that appears on a glazed surface. When the thermal expansion coefficient of the glaze is greater than that of the clay body, tensile stress develops in the glaze during the cooling stage after firing. When this stress exceeds the elastic limit, structural cracks—known as crazing—form on the surface. A key point is that crazing is distinguished from nyū, which refers to accidental cracks caused by external impact after completion. Crazing may sometimes be appreciated as part of a work’s character or as an expression of its age. In pieces fired at relatively low temperatures, where the body is not fully matured, crazing can cover the entire surface; such works are described as amate (“soft-fired”). When lightly tapped, these pieces produce a dull sound rather than a clear, resonant tone.

Crack (Nyu)

In porcelain—where perfection is expected—nyu is regarded as a flaw. In older ceramics, however, it is not considered as serious a defect and may even be appreciated as part of the piece’s natural character. Nyū refers to cracks that run from the rim toward the interior of a dish, bowl, or jar. Because they are caused by external impact, these cracks typically penetrate through both the glaze and the clay body, appearing on both the front and back surfaces. While nyu is treated as a defect in porcelain, in antique ceramics it can be accepted as one aspect of the work’s aesthetic landscape, and therefore cannot be dismissed outright.

Tori‑ashi (“Bird’s‑Foot” Crack)

This term refers to cracks that radiate outward across the interior well or the underside of a dish or jar. They are typically caused by external impact. The name tori‑ashi derives from their resemblance to the footprint of a bird.

Production Flaw

Production flaws refer to imperfections that occur during the manufacturing process. Even when they appear as chips or cracks, they remain beneath the glaze, which is a defining characteristic. Such flaws are known as yama-kizu or simply yama. Unlike damage caused by external impact after completion, these flaws are regarded as inherent features of the piece and may even be appreciated as part of its character.

Chip

These terms refer to damage caused when a portion of the rim or foot has broken away. Small areas of loss are called nomi-hotsu or ko-hotsu, while larger losses are distinguished as soge or kake.

Production Flaw (Kiln Adhesion Mark)

This term refers to a kiln flaw caused by foreign matter adhering to the surface of the piece during firing.

Yu-kire (Failed to Cover)

“Yu-kire” refers to a condition in which the glaze has not fully covered the surface, leaving part of the clay body exposed. It is also known as “yu-nuke.”

Yu-hage (Flaked Off)

“Yu-hage” refers to a condition in which only the glaze layer has flaked off, while the clay body remains intact.

Pitting (Mushikui)

“Pitting” refers to small areas where the glaze has fallen away due to differences in the shrinkage rates between the clay body and the glaze, leaving the underlying clay exposed. The term “mushikui” (“insect-eaten”) comes from its resemblance to tiny bite marks. It commonly appears on rims and edges where the glaze tends to be thinner. Although originally regarded as a flaw, tea connoisseurs came to appreciate its natural expression, valuing it as a rustic and aesthetically pleasing feature.

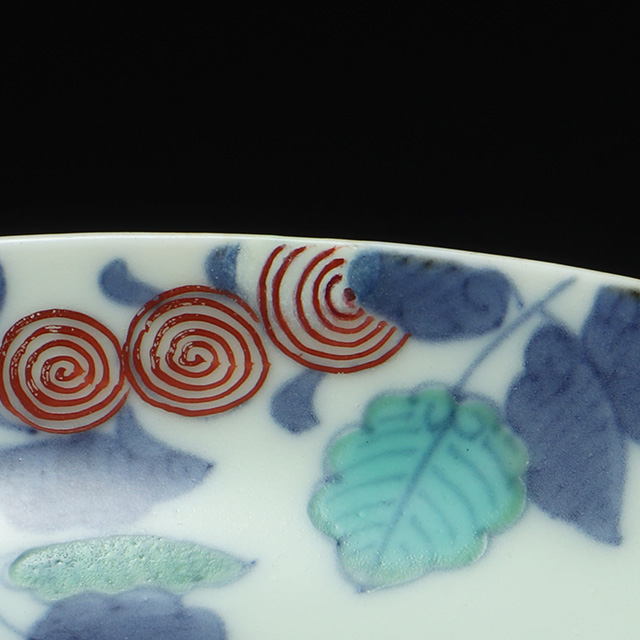

Gold Repair / Silver Repair / Maki-e Repair

The technique known as naoshi (restorative repair) serves both to reinforce a flaw and to refine the appearance of the piece. Repairs executed with gold or silver are the most common, and their finishes often possess an aesthetic quality in their own right. In some cases, repairs embellished with maki‑e decoration transcend mere restoration and rise to the level of artistic expression.

Tomo‑naoshi (repair)

“Tomo‑naoshi” refers to a type of restoration in which the traces of damage are carefully concealed by matching the surrounding color tones, patterns, and surface textures. In many cases, the restored areas can be identified under ultraviolet light, though in recent years highly sophisticated tomo‑naoshi that show no such reaction have also become more common.

Yobitsugi (Patch-Inlay Repair)

Yobitsugi is a restoration method in which a fragment—either from the same type of vessel or one that harmonizes aesthetically—is “called in” to fill a missing section. This technique carries a uniquely ceramic sensibility, and the supplemented area is sometimes appreciated as a scenic element in its own right.