Chinese Antique (Han-Song Dynasty)

中国古美術(漢-宋時代)

Chinese Antique (Han-Song Dynasty)

Home > Fine Arts > Chinese Antique (To the Artworks Information Page)

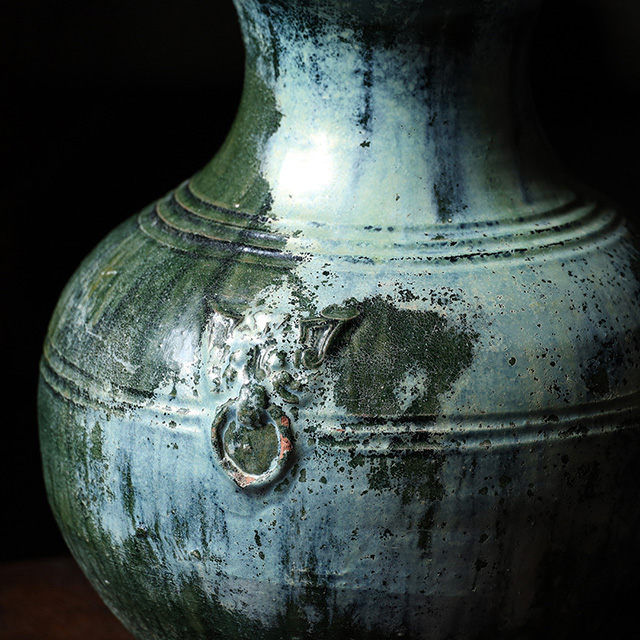

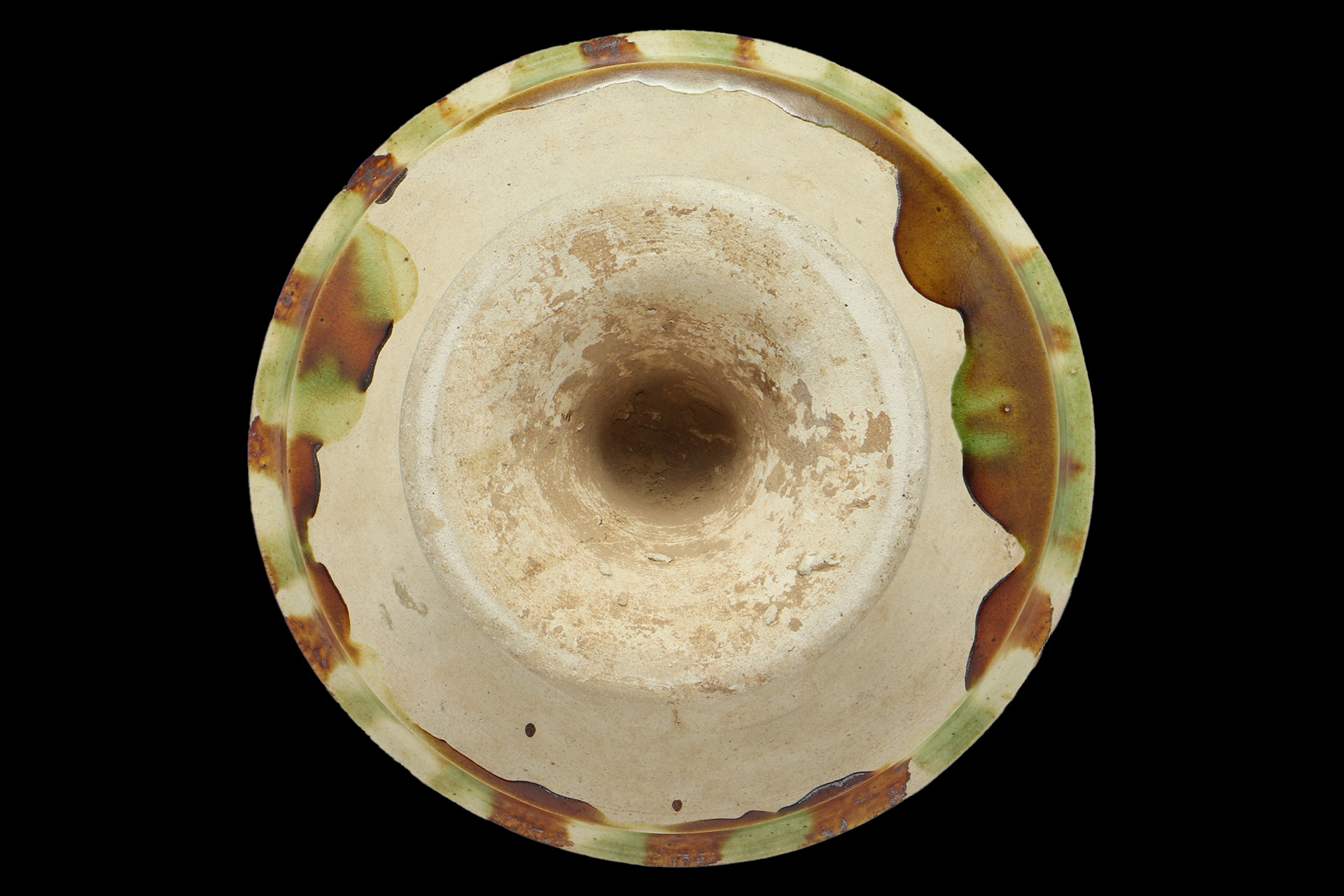

Han-Green-Glaze

Brightly colored lead glazed pottery is a type of burial accessory that represents prayers for the deceased, and was made in large quantities during the han dynasty. In ancient china, the afterlife was thought to be an extension of the present world, and so objects such as jar, tableware, animal, house, and well were created to enable people to live a rich life after death, just as they did in life. The base is fine and contains a lot of iron, and when copper oxide is used as a coloring agent on the lead glaze, the green color is obtained. Low temperature lead glaze evaporates when it reaches temperatures of over 1,000℃, so it was fired at a low temperature of 700 to 800℃. Green-glaze was popular in shaanxi and henan provinces around the 1-3th century of the later han dynasty, and the core workshops were located in the two capitals of chang’an and luoyang. This is because people of this class were concentrated in the suburbs of the capital, and it is inevitable that excavated examples would be concentrated in this area. Many of the green-glaze have a silvery, iridescent coating on their surfaces due to the chemical changes caused by lead in the soil over many years, and are praised for their mysterious beauty and are called “Silverization” or “Laster”. The brown-glaze(colored by iron oxide)that flourished during the western han dynasty faded into the shadow of the heyday of the green-glaze, and the production volume of the later developed green-glaze is overwhelmingly large. Although the glaze is thick and generous, the inside of the jar or bottle is unglazed, and since it was a burial accessory and not a practical item, there would have been no problem as long as the glaze was applied only to the visible parts on the outside. Green and brown glazes are mostly used alone, but occasionally both glazes are used together on the same work of pottery. After applying a brown-glaze over the entire surface, green-glaze is added in some areas or colored with green-glaze. Conversely, there are no known cases of adding brown-glaze to the green-glaze. When these two glazes are used together, the green-glaze becomes unstable and peels off, and there are very few examples of beautiful two colored glazed. Because the firing method used was to overlap the mouths of the jars, the glaze on the rim of the mouth has peeled off, and when the jars were filled upside down in the kiln, the glaze flowed from the neck toward the mouth, causing glaze pooling. Han green-glaze was considered out of reach until around the 1970s, but with china’s reforms and infrastructure development, tombs from the han and tang dynasties were discovered in the 1980s, and large quantities of han green-glaze and tang-sancai ware were brought to japan, upsetting the supply and demand balance. The works that have been treated as masterpieces are different from the large number of excavated artifacts, and are not works that are considered to be all the same. The works, which have been treated as masterpieces, continue to fascinate people with their fresh green-glazed and beautiful silverization.

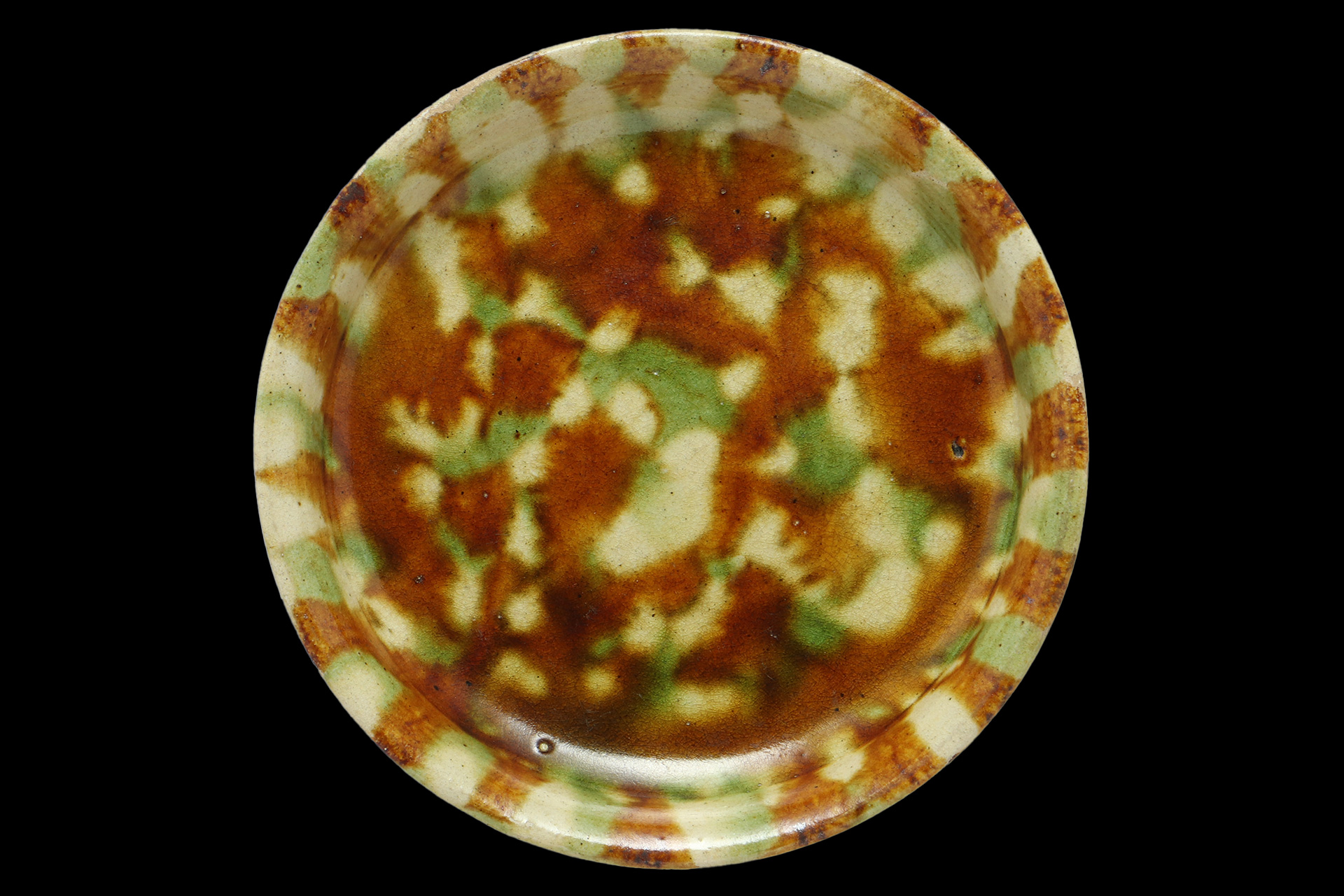

Tang Sancai

Tang sancai refers to tri‑colored lead‑glazed wares produced primarily at kilns in and around Xi’an (formerly Chang’an) and Luoyang during the Tang dynasty. These objects were originally created as mingqi (tomb furnishings) rather than for daily use. They adorned the tombs of aristocrats and high officials with brilliant splendor and stand today as masterpieces symbolizing the cultural exchange between East and West along the Silk Road. In 1905 (Guangxu 31), a large quantity of Tang sancai was unearthed during construction of the Bianluo Railway linking Kaifeng (Bianjing) and Luoyang. The discovery of these vividly colored mingqi, which had been almost unknown until then, astonished the world, and Western collectors eagerly sought them. In this way, Tang sancai rapidly established an international reputation as a quintessential expression of Chinese ceramics. In Japan, mingqi had long been regarded with a degree of aversion, yet collectors captivated by the beauty of Tang sancai gradually emerged. Their appreciation fostered a new collecting ethos—kansho toji, the connoisseurship of ceramics for their pure aesthetic qualities. Among the leading collectors were Moritatsu Hosokawa (Eisei Bunko Museum), Koyata Iwasaki (Seikado Bunko Art Museum), Tamisuke Yokogawa (Tokyo National Museum collection), and Sazo Idemitsu (Idemitsu Museum of Arts). Most excavated examples come overwhelmingly from Xi’an in Shaanxi Province and Luoyang in Henan Province, the political centers of aristocrats and high-ranking officials, followed by Yangzhou in Jiangsu Province, which flourished as a major port of trade. Recent archaeological investigations have revealed that their distribution extended widely across China—including Liaoning, Hebei, Shanxi, Shandong, Gansu, Hubei, Anhui, and Jiangxi Provinces—demonstrating an exceptionally broad geographical spread. The production process involved shaping a soft, highly plastic clay body, bisque‑firing it at around 1,200°C, cooling it, applying a base transparent glaze, and then adding green, brown, and other lead glazes before low‑temperature firing at approximately 800–900°C. During firing, the base glaze melted to form the ground layer, allowing the colored glazes to flow and permeate. Where the glazes met, they fused naturally, creating vivid and richly varied patterns. Although the standard palette consists of white, green, and brown, works incorporating cobalt blue (lancai) or employing only two colors are also collectively referred to as Tang sancai. The influence of Tang sancai was far‑reaching. It significantly shaped the ceramic traditions of neighboring regions, including contemporaneous “Liao sancai,” Japan’s “Nara sancai,” as well as “Silla sancai” and “Bohai sancai.”

Mirror with Grape and Beast Design

This mirror, a representative example of the cosmopolitan bronze mirrors of the Tang dynasty, features on its reverse a “sea beast”—a lion symbolizing creatures from distant lands—together with grape‑vine scrolls of Western origin that signify fertility and abundance, all rendered with remarkable precision. Many such mirrors were brought to Japan from the Asuka through the Nara periods, and examples have been recovered from the Shosoin Repository, the Five‑story Pagoda of Horyu‑ji, and the Takamatsuzuka Tomb. Their influence extended to domestic production as well, inspiring the widespread casting of locally made mirrors modeled after Tang prototypes.

Qingbai Ware

The blue color of qingbai ware comes from the reduction firing of trace amounts of iron contained in the glaze. Starting with the jingdezhen kiln in jiangxi province, it was also fired in guangdong, fujian, zhejiang, anhui, and henan provinces.

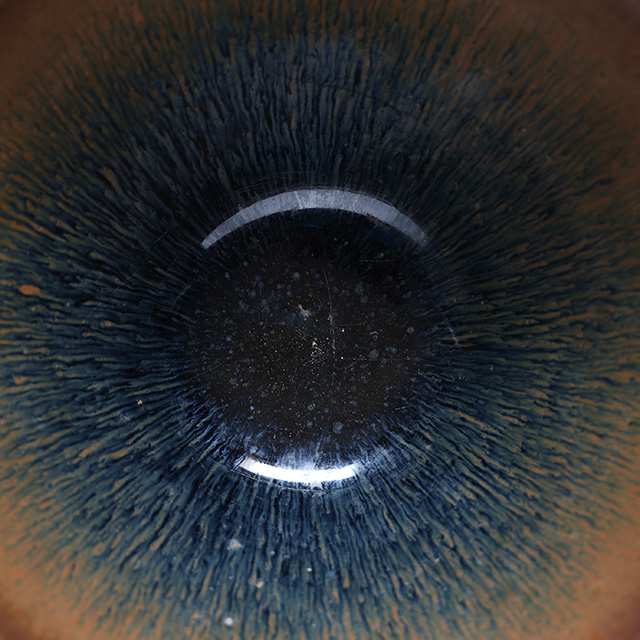

Tenmoku Tea Bowl

Tenmoku tea bowl is a type of bowl used for drinking powdered green tea (matcha). At Mount Tianmu, a renowned Zen Buddhist site located on the border between Zhejiang and Anhui Provinces in China, many Japanese monks gathered during the Kamakura period to pursue their studies. These monks brought back to Japan the black‑glazed bowls that were used daily in the monastery, and the name tenmoku is said to derive from this origin. Tenmoku tea bowls possess distinctive formal characteristics: a low, compact foot; a waist that flares in a funnel-like shape; a slightly constricted interior that then turns outward to form a beaked rim; and an unglazed area around the foot. Among the principal types are yohen tenmoku, yuteki tenmoku, nogime tenmoku (hare’s‑fur tenmoku), tortoiseshell tenmoku, and haikatsugi tenmoku (ash‑covered tenmoku). Many examples feature gold or silver mounts on the rim, an embellishment intended to soften the unpleasant mouthfeel caused by the roughness of the clay body. From the latter half of the Tensho era (1573–92), the central role of the tea bowl gradually shifted to Korean bowls such as korai chawan. Tenmoku bowls came to be used primarily for ceremonial purposes, and the practice of pairing them with a special tenmoku-dai stand became established. Today, eight tea bowls are designated as National Treasures in Japan, and nearly half of them are tenmoku bowls. These include the three Chinese yohen tenmoku tea bowls (held by the Seikado Bunko Art Museum, the Fujita Museum, and Ryokoin of Daitoku-ji), one yuteki tenmoku tea bowl (The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka), and one tortoiseshell tenmoku tea bowl (Shokoku-ji Jotenkaku Museum). The remaining three are the Korean oido tea bowl known as “Kizaemon” (Kohoan, Daitokuji), the Japanese e-Shino tea bowl “Unohanagaki” (Mitsui Memorial Museum), and Fujisan, a work by Hon’ami Koetsu (Sunritz Hattori Museum of Arts). This grouping clearly illustrates the exceptional esteem in which tenmoku tea bowls have long been held as the highest rank among tea bowls.

We sell and purchase Chinese Antique (Han-Song Dynasty)

We have a physical shop in Hakata-ku, Fukuoka City, where we sell and purchase "Chinese Antique (Han-Song Dynasty)" works. Drawing on a long career and rich experience in dealing, we promise to provide the finest service in the best interests of our customers. With the main goal of pleasing our customers, we will serve you with the utmost sincerity and responsibility until we close the deal.