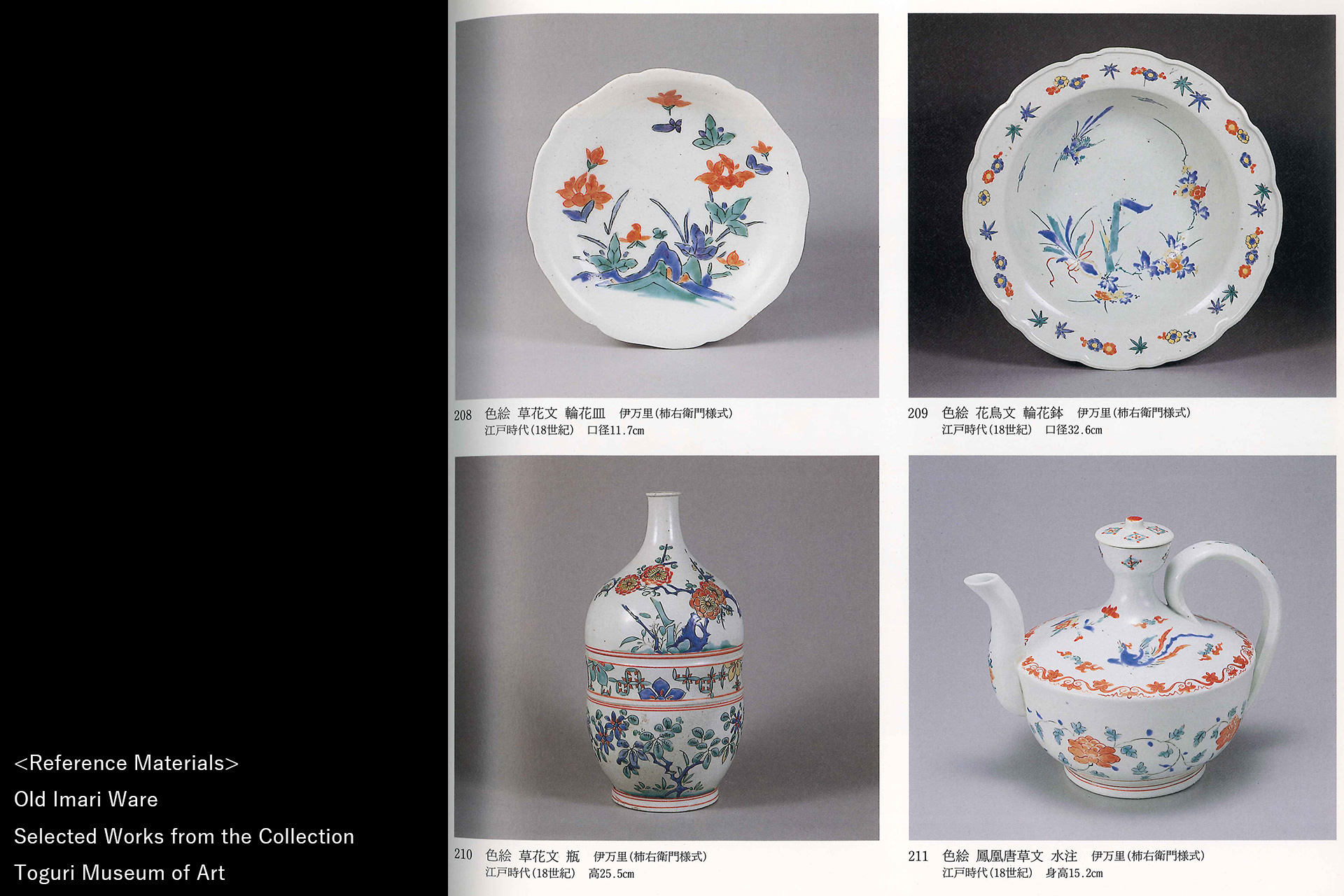

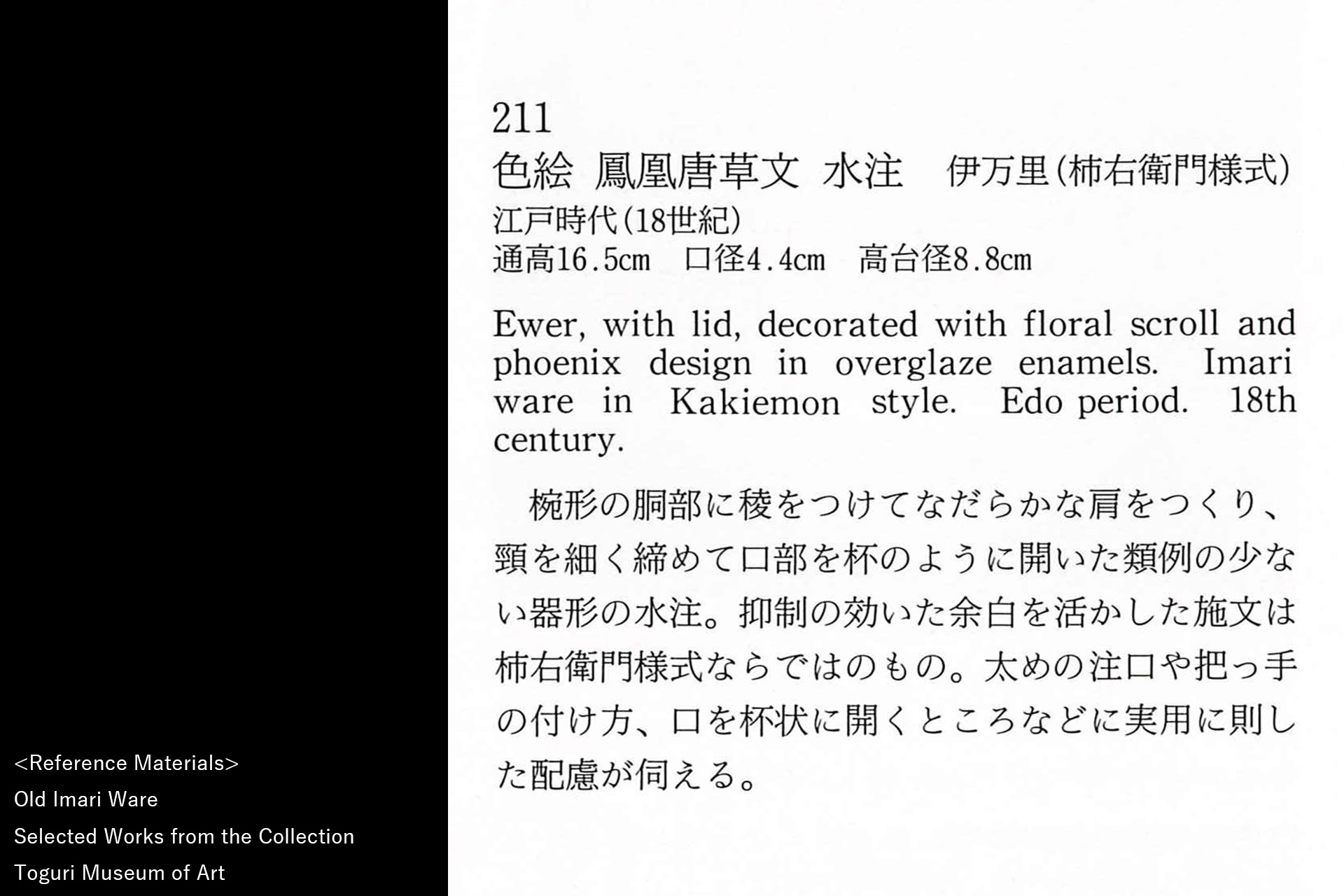

Kakiemon-Style Polychrome Ewer with Phoenix and Arabesque Motif (Edo Period)

Sold Out

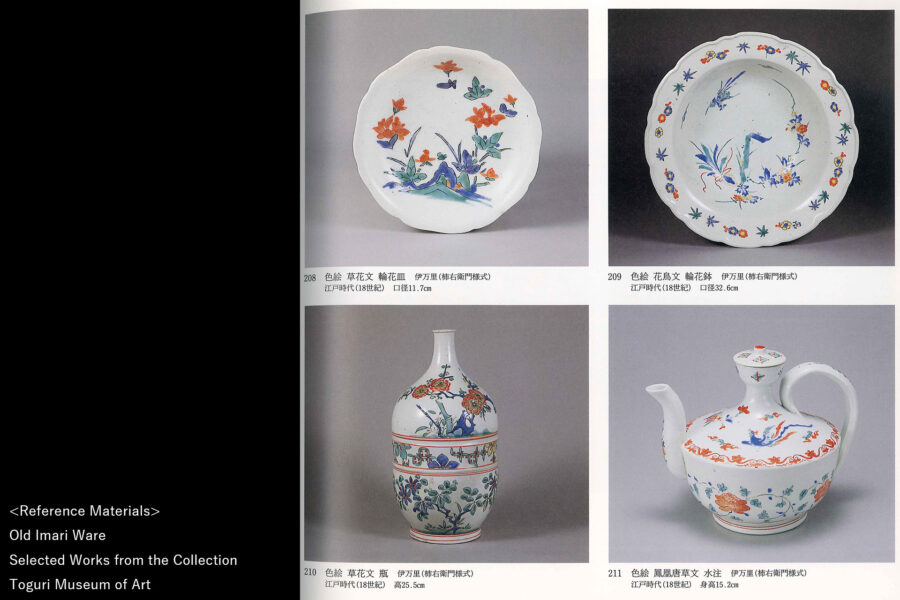

This piece is counted among the finest examples of Kakiemon-style porcelain, a category that once catered to the tastes of Europe’s royal and aristocratic courts. The gently swelling body rises into a slender neck, while the gracefully formed spout and handle achieve a sophisticated balance between functionality and ornamentation. The milky-white porcelain surface provides a luminous ground for the finely executed and vibrant overglaze enamels: a phoenix—an auspicious symbol—soars across the front, while the reverse is adorned with a pomegranate motif representing abundance and the prosperity of future generations. Three-dimensional works of this type were notoriously difficult to fire successfully, resulting in a very low yield and making surviving examples exceedingly rare. Many extant pieces show damage or restorations to the handle or spout, yet this ewer remains in remarkably fine condition, far better than one could reasonably expect. Although the original matching lid has been lost, the rim is glazed, allowing the vessel to present a natural and harmonious appearance even without it. A comparable example is preserved in the Toguri Museum of Art.

-------------------------------------------------------

⇒ Collection of the Toguri Museum of Art (External Site)

-------------------------------------------------------

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 260115-1

- Period

- Edo Period

Late 17th Century

- Weight

- 662 g

- Width × Depth

- 18.5 × 14.5 cm

- Height

- 16.0 cm

- Base Diameter

- 9.4 cm

- Fittings

- Paulownia Box (Cloth‑Lined Type)

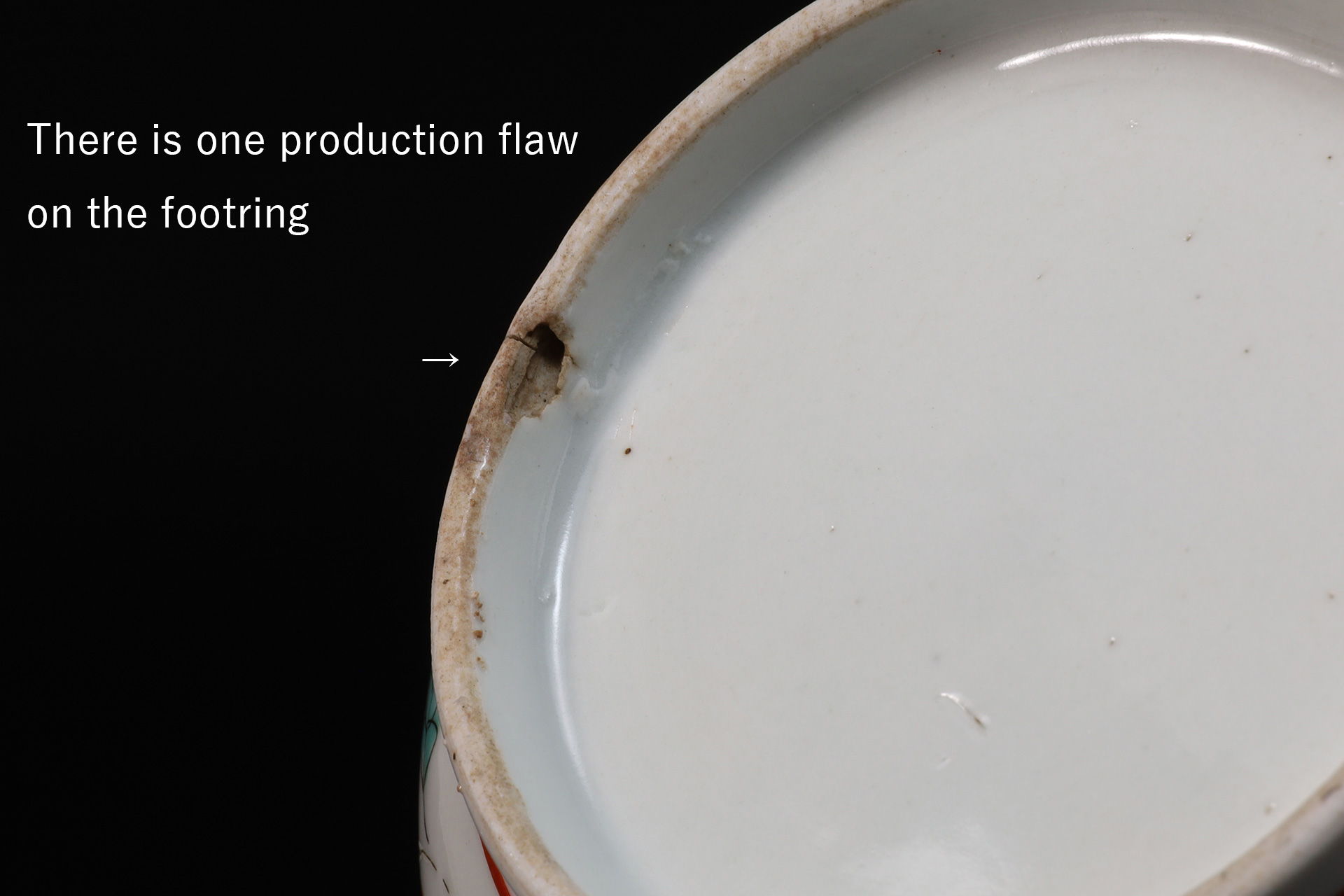

- Condition

- - Perfect Condition

- It is overall in good condition

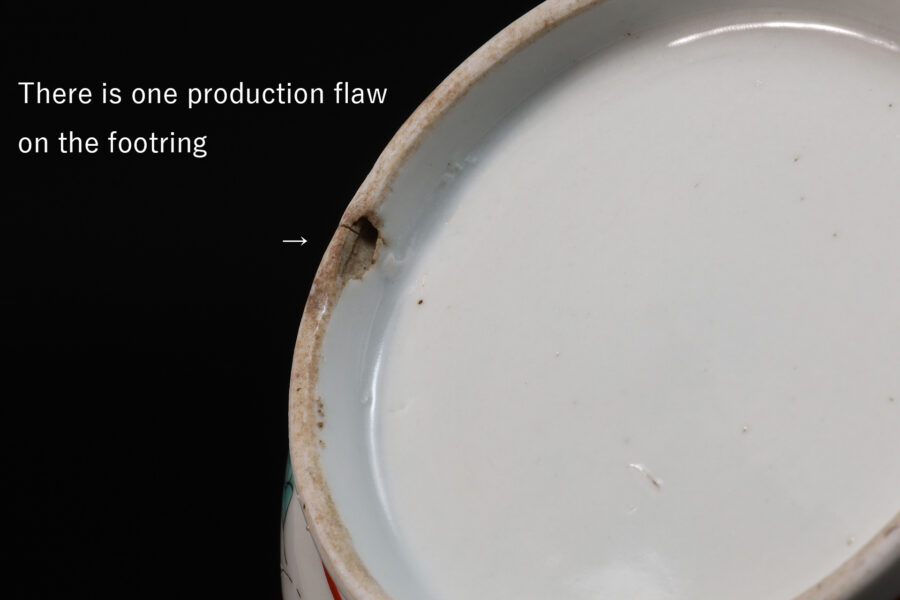

- Production Flaw

- - There is one production flaw on the footring (Refer to the image)

Kakiemon-Style

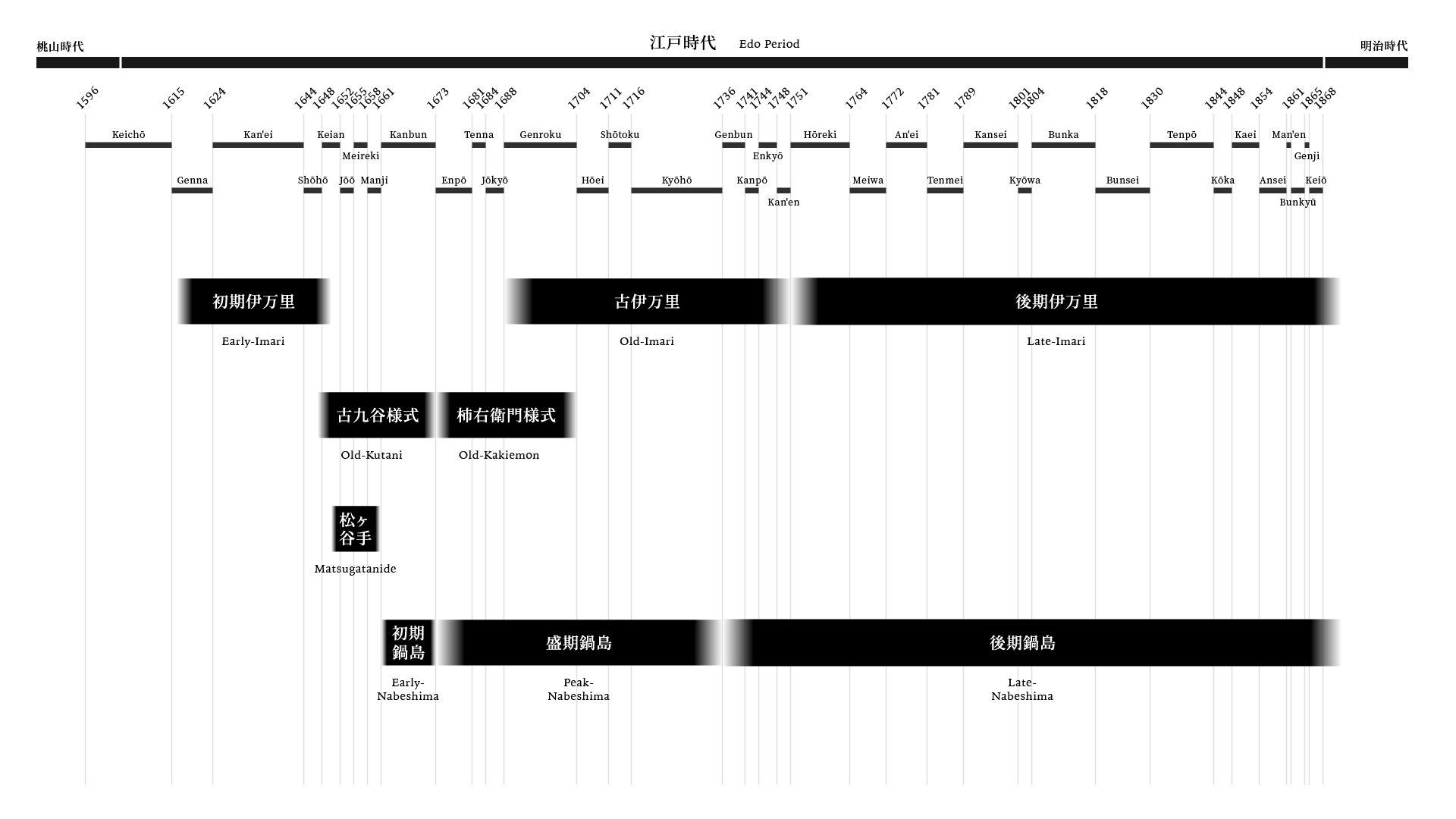

Kakiemon-style refers to a distinctive category of Imari ware primarily fired during the Enpō era (1673–81). These works were not exclusively produced by the Kakiemon family; rather, they emerged as a collective response to large-scale export orders from the Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.), and were completed across various kilns in Hizen Arita. The term “style” thus denotes a broader aesthetic, now widely recognized as “Kakiemon” in its extended sense. Characterized by refined compositions that embrace negative space and delicate brushwork by skilled painters, these porcelains possess an elegant and noble beauty. Their exquisite craftsmanship captivated European royalty and aristocracy, earning enduring popularity among the V.O.C.’s cargo offerings. Among the most celebrated features is the nigoshide body – a soft, milky-white porcelain base that heightens the brilliance of overglaze enamels. This innovation profoundly influenced the development of European porcelain, notably at Meissen and Chantilly. Signatures often include the stylized “uzu-fuku (spiral-fuku)” mark, where the character for “fortune” is rendered in a swirling motif. Other marks such as “kin (gold)” and “inishiebito (ancient person)” appear on particularly fine examples. While exported Ko-Imari ware from the Edo period also displayed opulent beauty, it was the Kakiemon-style that drew the greatest admiration. After World War II, many works that had journeyed to Europe were repatriated in large numbers. The sheer volume of exported works far exceeds the domestic legacy, underscoring the style’s original purpose as an export commodity. Notably, works that blur the distinction between Ko-Imari and Kakiemon-styles are often referred to as Kakiemon-de. In recent years, the term “Kakiemon” has come to be applied more broadly – even to later works of lesser refinement – reflecting evolving perceptions of the style.

The Era Establishing the Export Industry Between the VOC and Japan

The east india companies were chartered companies established by european countries in the 17th century(the british in 1600, the dutch in 1602, and the french in 1604)for trade with the orient. The dutch east india company’s monogram, consisting of the initials “VOC”(Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie), was its emblem, was put on warehouses, coins, cannons, flags, ceramics, etc, to indicate the company’s ownership of products. In addition to spices, its original product of interest, the company also sought porcelain that could not be produced in europe and traded with china. The hard porcelain imported from china was called “White Gold” and was traded as a valuable item, rivaling gold in value. Once vast quantities of porcelain, a luxury item and symbol of wealth, were brought to europe, its beauty deeply impressed europeans, encouraging china to produce even more products. However, due to the civil war following the change between the ming and qing dynasties in the 1640s and policies restricting overseas trade, the quality of porcelain fired in the jingdezhen kiln and other porcelain kilns became inferior, making it almost impossible to buy porcelain products. As a result, the company sought japanese porcelain, which could be produced without interruption, as an alternative. In 1653, japan entered into an export deal with the dutch east india company(VOC)for imari ware. In 1659, japan received a massive order of about 56,700 pieces, ushering in a glamorous era for the export industry in japan. The new feudal system of the tokugawa government beginning to take shape, imari ware was thrust into the limelight of the international market as a product of the nabeshima clan of the saga domain. Because europe demanded identical replacements for chinese porcelain, many early pieces exported imitated the fuyode style and other styles from the late ming dynasty. The large volume of orders from the VOC led to significant technical advances at the hizen arita kilns, and the expanded capacity of these kilns made it possible to produce many jinko tsubo(agarwood jar). The exported porcelains varied widely in shape. Even considering this, it is clear that the expansion of trade with the VOC contributed to the significant flourishing of imari ware. When the qing dynasty lifted the qian-jie-ling(order blocking maritime traffic and trade)in 1684, exports of chinese porcelain resumed, and from around 1712, exports boomed. Chinese porcelain once again regained its dominant position in the market. As a result, imari ware lost out in market competition with chinese porcelain, which boasted quality, quantity, and low prices. China overwhelmingly outnumbered japan in the total number of porcelain exported through trade with the VOC. The establishment of meissen, the first porcelain kiln in europe, in 1710 contributed to the gradual decline of porcelain exports from asia. The official japanese porcelain trade ended in 1757 with a mere 300 pieces and then was left to private trade by the trading houses.