This is a Tang sancai figurine of a court lady, embodying the splendor and refinement of the flourishing Tang dynasty culture. With both hands gently placed before her and a serene expression upon her face, her graceful figure evokes the refined presence of a court lady. In ancient China, the afterlife was regarded as a continuation of the earthly world, and such tomb figurines were placed to attend to their masters in the next life as well. The prayers and longing for beauty entrusted to these figures continue to resonate across a millennium, stirring the hearts of viewers and conveying the enduring breath of an ancient civilization.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 260108-2

- Period

- Tang Dynasty

8th Century

- Weight

- 468 g

- Width × Depth

- 7.5 × 7.5 cm

- Height

- 25.6 cm

- Fittings

- Display Stand

Paulownia Box (Cloth‑Lined Type)

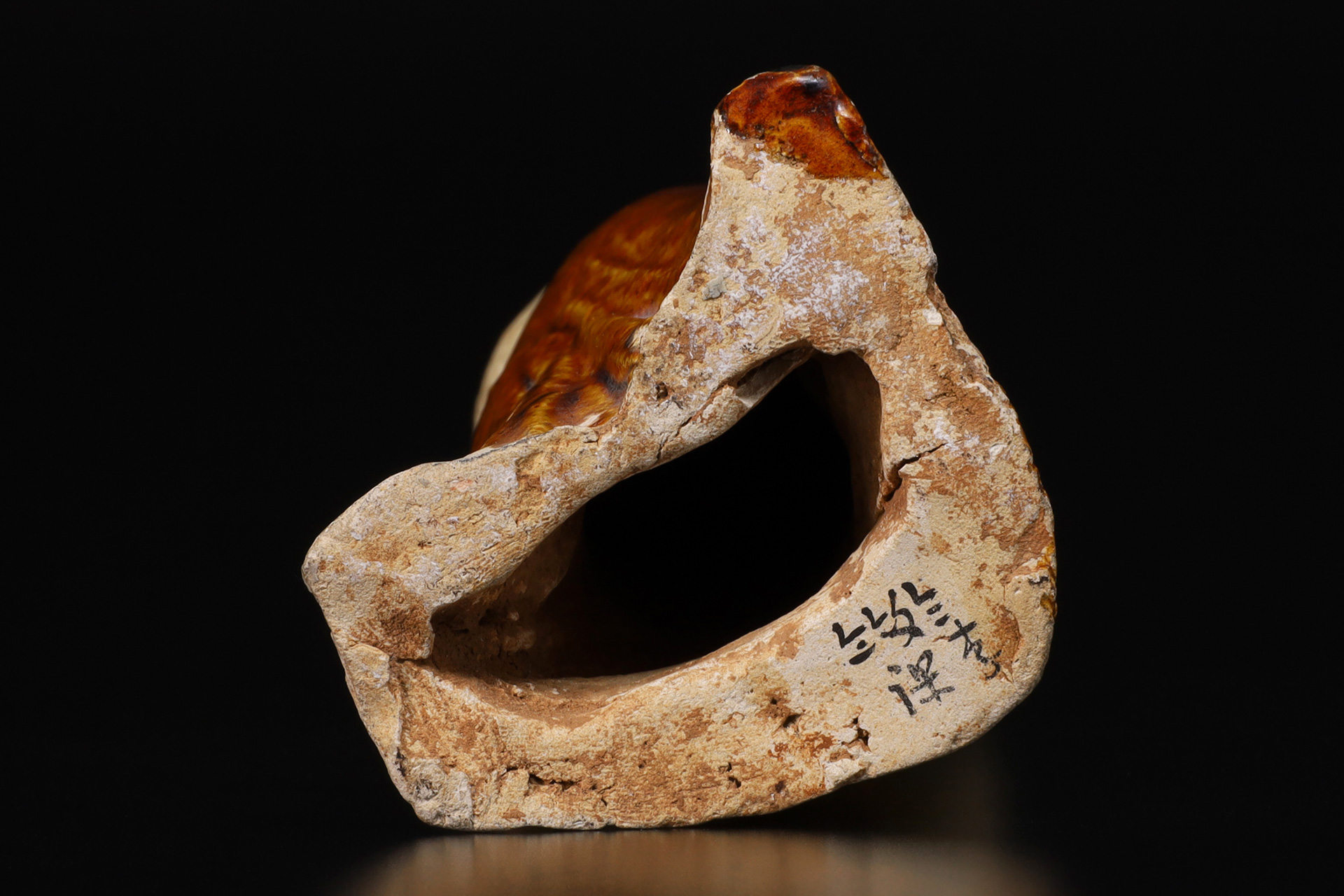

- Condition

- Good

The lustrous, vibrant glazes are beautifully preserved, with no conspicuous repairs or other significant damage, and the piece remains in excellent condition.

Tang Sancai

Tang sancai refers to tri‑colored lead‑glazed wares produced primarily at kilns in and around Xi’an (formerly Chang’an) and Luoyang during the Tang dynasty. These objects were originally created as mingqi (tomb furnishings) rather than for daily use. They adorned the tombs of aristocrats and high officials with brilliant splendor and stand today as masterpieces symbolizing the cultural exchange between East and West along the Silk Road. In 1905 (Guangxu 31), a large quantity of Tang sancai was unearthed during construction of the Bianluo Railway linking Kaifeng (Bianjing) and Luoyang. The discovery of these vividly colored mingqi, which had been almost unknown until then, astonished the world, and Western collectors eagerly sought them. In this way, Tang sancai rapidly established an international reputation as a quintessential expression of Chinese ceramics. In Japan, mingqi had long been regarded with a degree of aversion, yet collectors captivated by the beauty of Tang sancai gradually emerged. Their appreciation fostered a new collecting ethos—kansho toji, the connoisseurship of ceramics for their pure aesthetic qualities. Among the leading collectors were Moritatsu Hosokawa (Eisei Bunko Museum), Koyata Iwasaki (Seikado Bunko Art Museum), Tamisuke Yokogawa (Tokyo National Museum collection), and Sazo Idemitsu (Idemitsu Museum of Arts). Most excavated examples come overwhelmingly from Xi’an in Shaanxi Province and Luoyang in Henan Province, the political centers of aristocrats and high-ranking officials, followed by Yangzhou in Jiangsu Province, which flourished as a major port of trade. Recent archaeological investigations have revealed that their distribution extended widely across China—including Liaoning, Hebei, Shanxi, Shandong, Gansu, Hubei, Anhui, and Jiangxi Provinces—demonstrating an exceptionally broad geographical spread. The production process involved shaping a soft, highly plastic clay body, bisque‑firing it at around 1,200°C, cooling it, applying a base transparent glaze, and then adding green, brown, and other lead glazes before low‑temperature firing at approximately 800–900°C. During firing, the base glaze melted to form the ground layer, allowing the colored glazes to flow and permeate. Where the glazes met, they fused naturally, creating vivid and richly varied patterns. Although the standard palette consists of white, green, and brown, works incorporating cobalt blue (lancai) or employing only two colors are also collectively referred to as Tang sancai. The influence of Tang sancai was far‑reaching. It significantly shaped the ceramic traditions of neighboring regions, including contemporaneous “Liao sancai,” Japan’s “Nara sancai,” as well as “Silla sancai” and “Bohai sancai.”