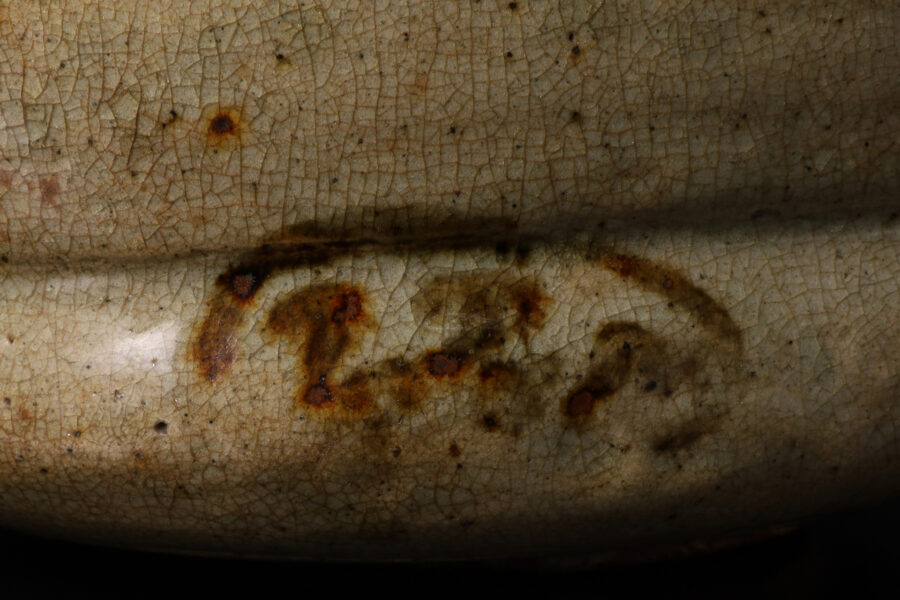

A kutsu-shaped E-Karatsu bowl that strongly reflects the influence of early Mino ware, known for its bold and vigorous spirit. The iron-painted motifs are rustic yet fluid, expressing the free and unrestrained aesthetic characteristic of Momoyama-period ceramics. The feldspar glaze applied from the interior to the outer surface has developed fine crazing, creating a surface that conveys the long passage of time through generations. The sharply carved, low-set foot and the iron-rich reddish-brown clay body further enhance its appeal. This piece was exhibited in the Gifu Prefecture Famous Treasures Exhibition, and it may be regarded as an excellent example of the artistic dialogue between Mino ware and old Karatsu across regional boundaries, revealing shared qualities in technique, form, and design.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 251213-1

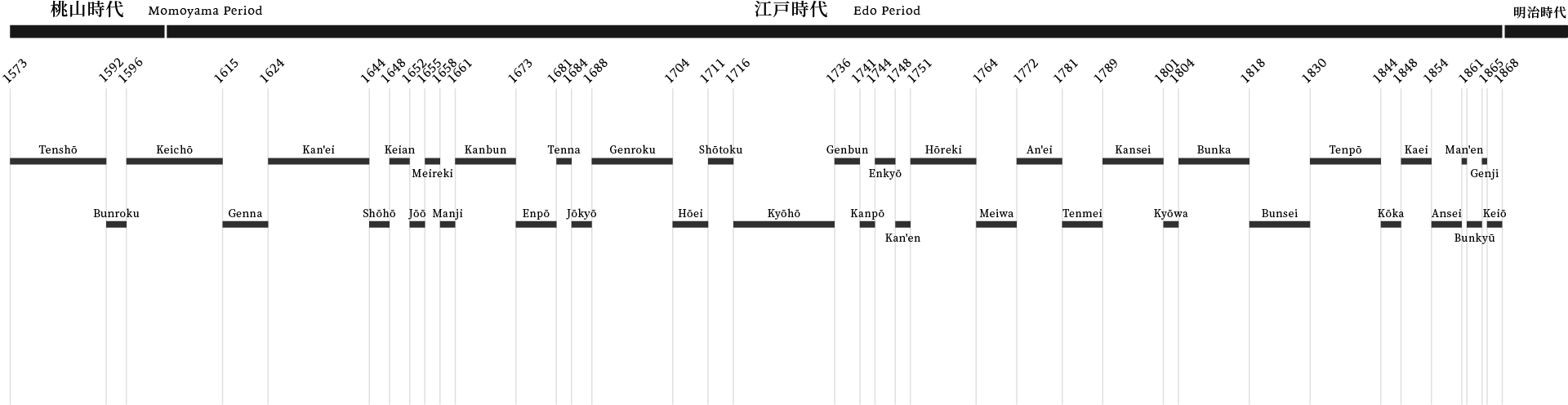

- Period

- Momoyama - Edo Period

End 16th Century - Early 17th Century

- Weight

- 797 g

- Width × Depth

- 16.9 × 13.8 cm

- Height

- 8.1 cm

- Base Diameter

- 7.0 cm

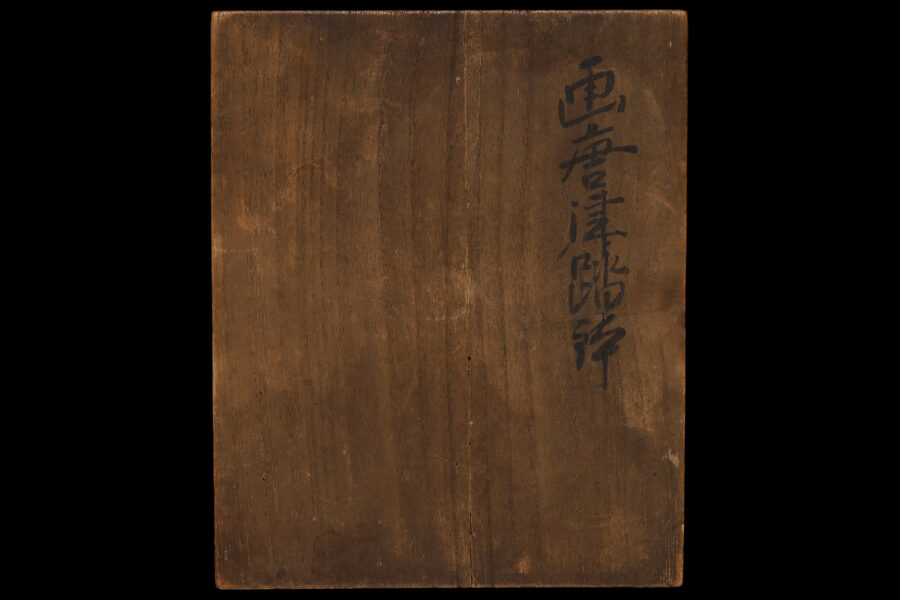

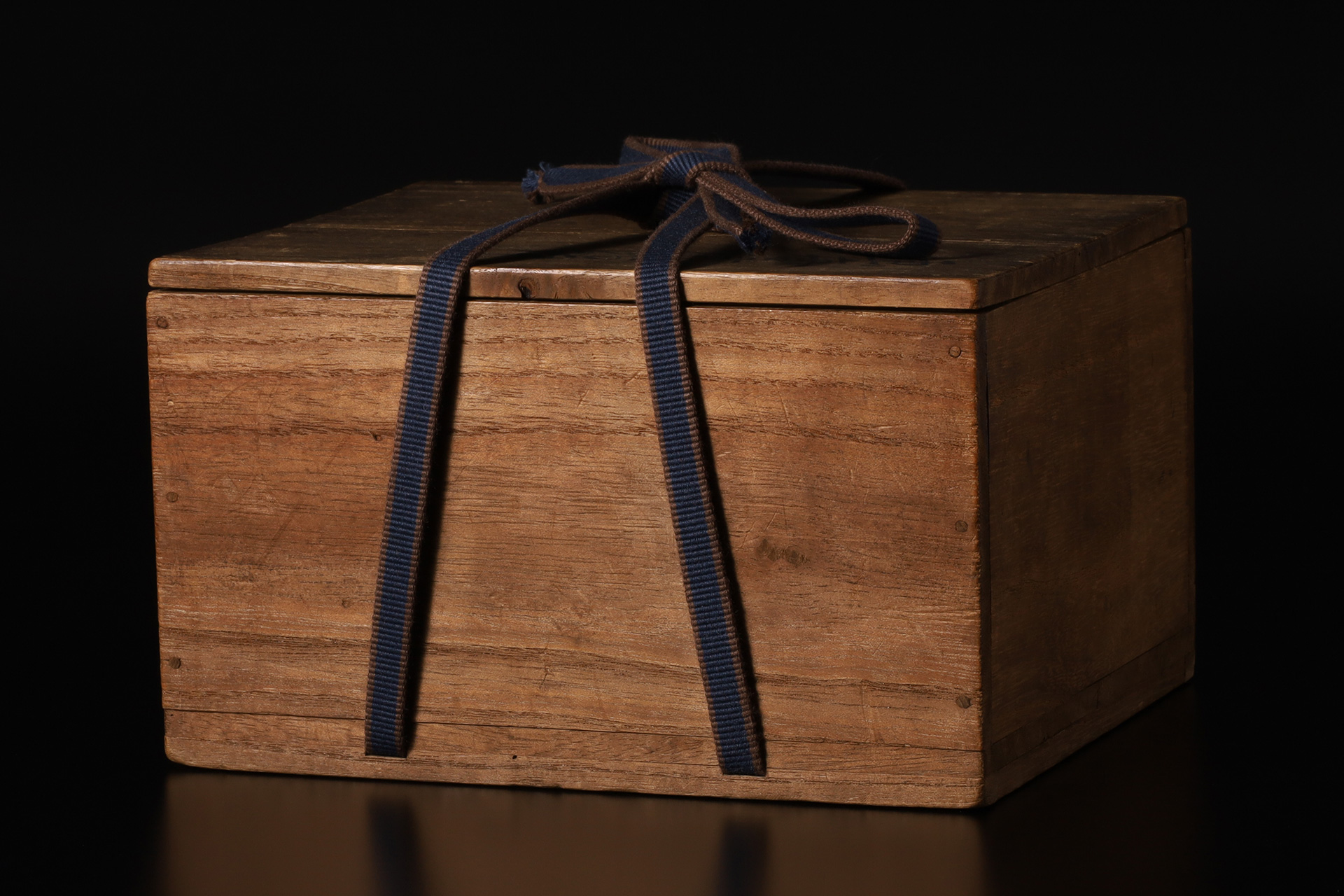

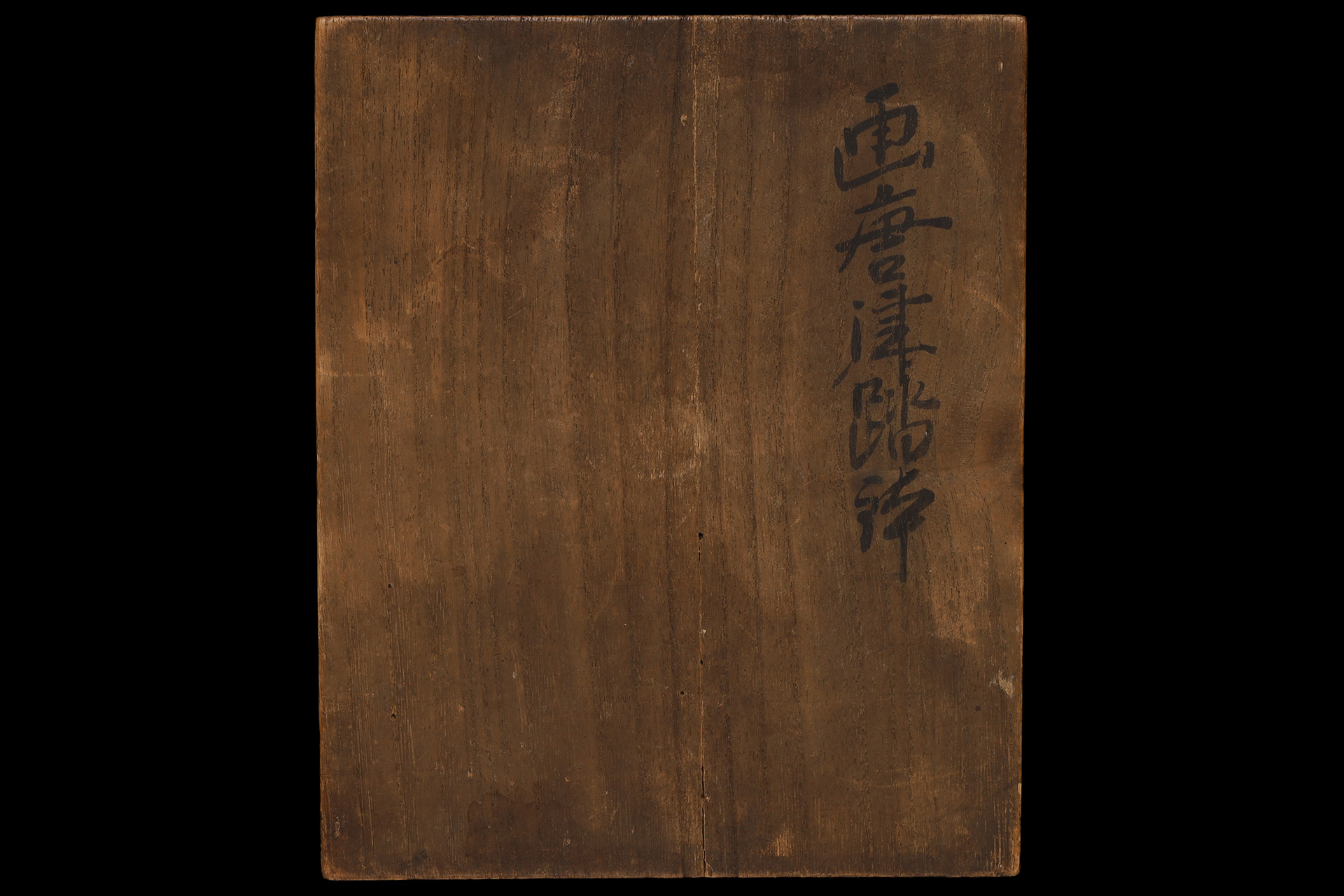

- Fittings

- Antique Box (Paulownia Box)

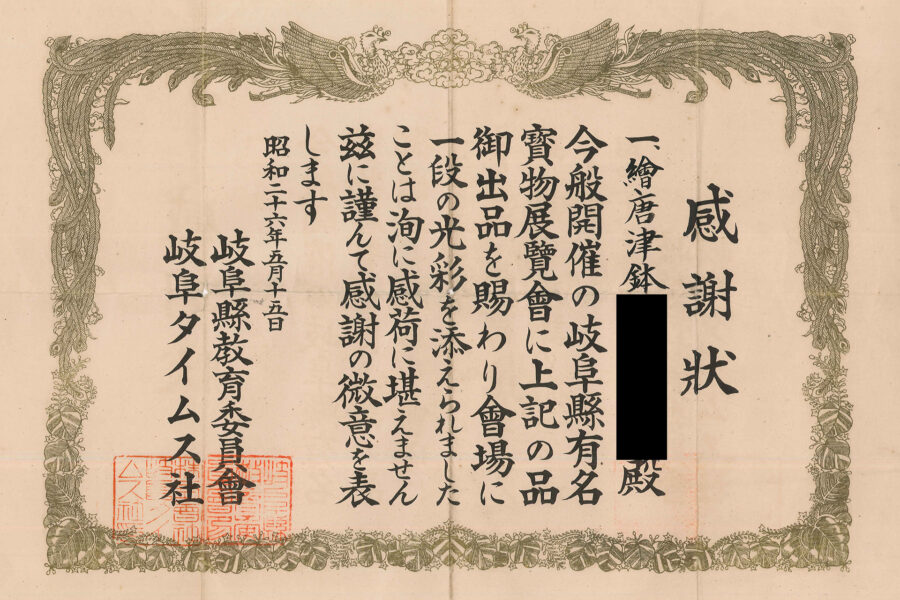

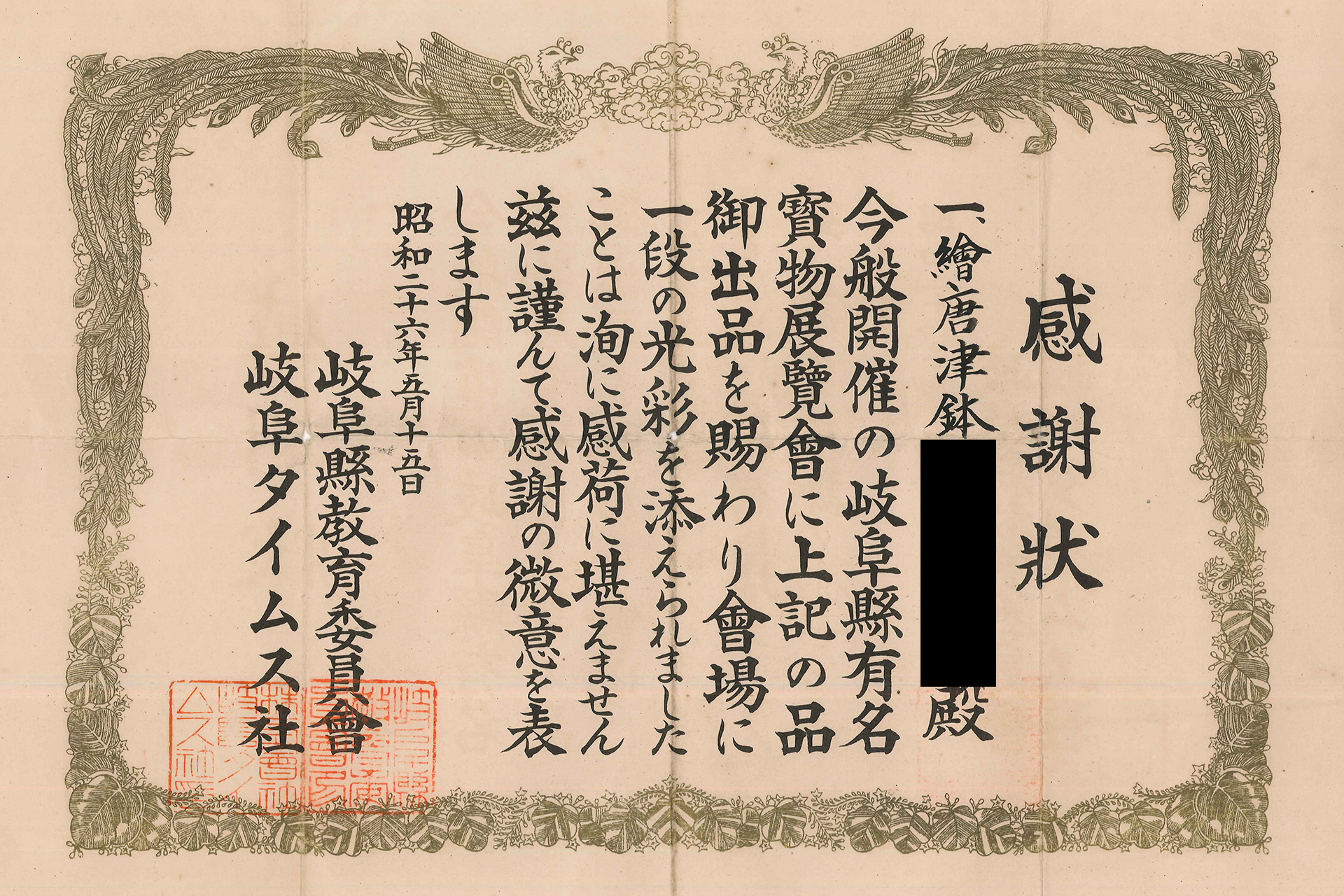

- Provenance

- Exhibited Work from the Gifu Prefecture Famous Treasures Exhibition

- Condition

- - Perfect Condition

- It is overall in good condition

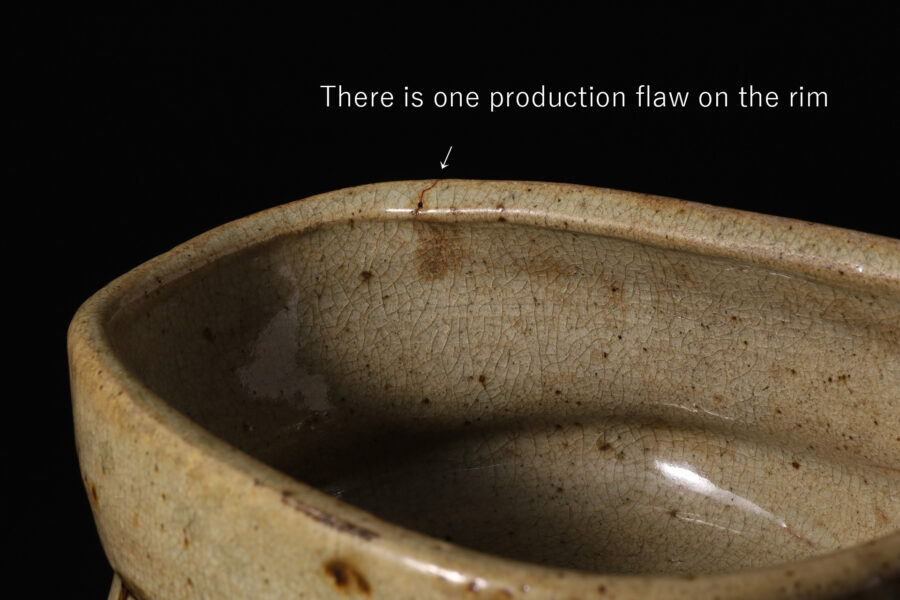

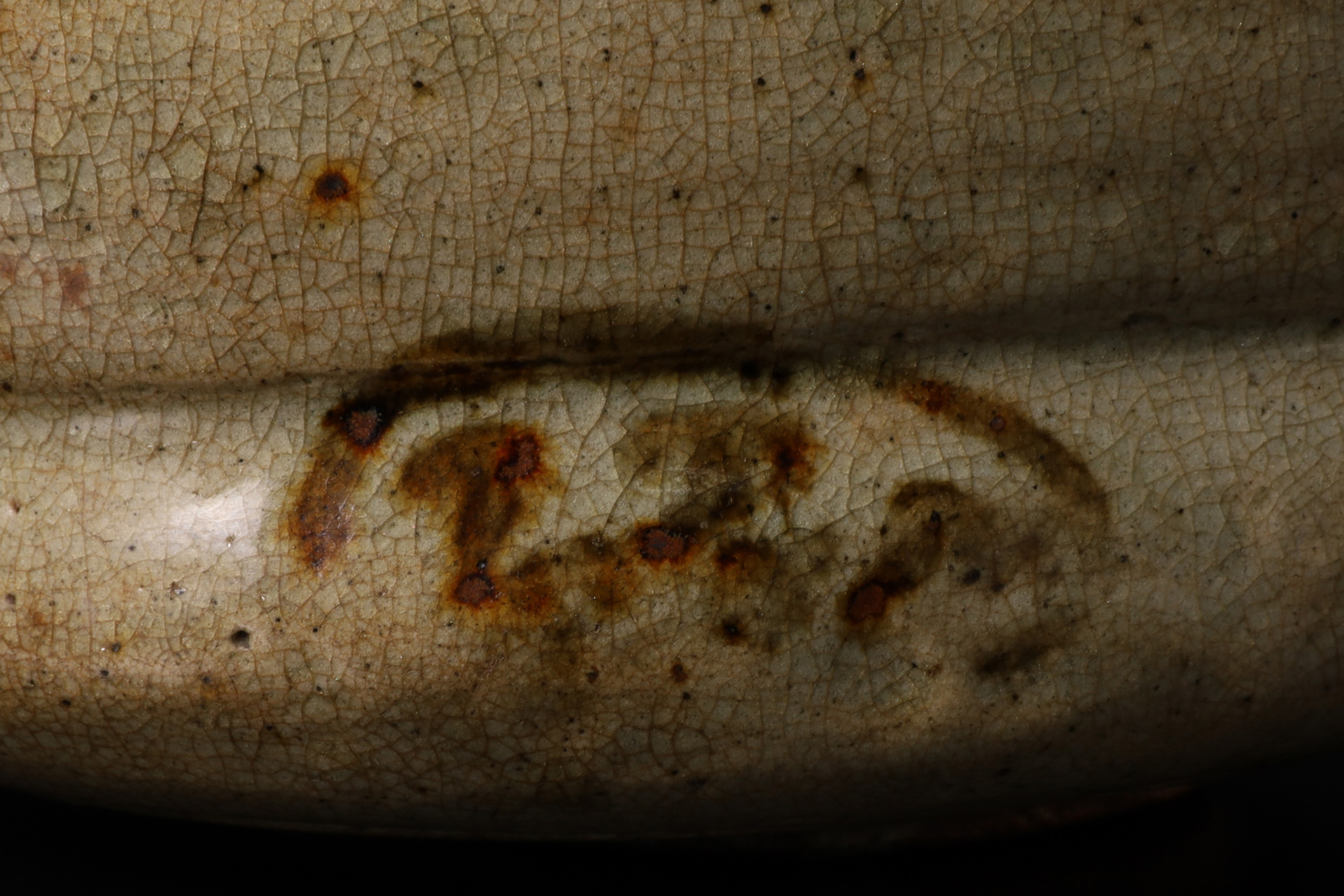

- Production Flaw

- - There is one production flaw on the rim (Refer to the image)

Ko-Karatsu

Karatsu ware refers to the pottery produced in the Hizen region, particularly within the Karatsu Domain of Hizen Province. Its name derives from the fact that these wares were shipped out from the port of Karatsu. Highly esteemed as tea ceramics, Karatsu ware has long been cherished by tea practitioners, to the extent that it is celebrated in the phrase, “First Raku, second Hagi, third Karatsu.” Its origins trace back to the late 16th century in the Kitahata area of Karatsu City in northern Saga Prefecture. It is said that Hata Chikashi, Mikawa-no-Kami, lord of Kishidake Castle, invited potters from the Korean Peninsula to establish kilns, and numerous early kiln sites from this formative period remain scattered around the castle town. When the Hata clan was dispossessed in 1593 (Bunroku 2) after incurring the displeasure of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the potters dispersed throughout Hizen—a historical event known as the “Kishidake Kuzure.” Shortly thereafter, Terasawa Hirotaka, Shima-no-Kami entered the domain, marking the establishment of the Karatsu Domain. This dispossession and the subsequent abandonment of the kilns serve as important evidence that Karatsu ware was already being produced before 1593, that is, during the Tensho era (1573–92). The techniques brought by Korean potters during the Bunroku–Keicho invasions (1592–98) further supported the flourishing of Karatsu ware from the Momoyama period into the early Edo period. During Hideyoshi’s encampment at Nagoya Castle, Furuta Oribe is said to have stayed in the region for about a year and a half from 1592 (Bunroku 1), providing guidance to the various Karatsu kilns. Moreover, the multi‑chamber climbing kiln (renbo‑shiki noborigama) was transmitted from Karatsu to Mino, where it was constructed at the Kujiri Motoyashiki site. The influence of Korean ceramic technology on Japanese kiln culture was profound and far‑reaching. The name “Karatsu ware” first appears in the Oribe Tea Gathering Records (Oribe chakai‑ki) of 1602 (Keicho 7) as “Karatsu‑yaki dish,” and it is frequently mentioned throughout the Keicho era (1596–1615). By the mid‑17th century, the term “Ko‑Karatsu” (“Old Karatsu”) also appears, indicating that its historical value was already recognized at that time. Although much of Karatsu ware was mass‑produced for everyday use, the popularity of tea preparation from the Momoyama to early Edo periods brought these wares to the attention of tea connoisseurs, who began to appreciate them as tea ceramics. Some pieces were even made to order for tea masters, and such works are highly valued today for their rarity. In the 17th century, the discovery of porcelain stone at Izumiyama by the immigrant potter Yi Sam‑pyeong (Japanese name: Kanagae Sanbei) and his success in porcelain production brought a major turning point to Karatsu ware. The rise of Imari ware led to the decline of Karatsu ware; although distinctive styles such as Mishima‑Karatsu and Nisai‑Karatsu emerged in the early Edo period, they could not rival the appeal of Ko‑Karatsu. Thereafter, only the official kilns (the “O‑chawan‑gama”) continued in limited operation. In the early Showa period, research by scholars such as Kanehara Tohen (1897–1951), Mizumachi Wasaburo (1890–1979), and Furutachi Kuichi (1874–1949) advanced significantly, and tens of thousands of ceramic shards were excavated from old kiln sites throughout the Hizen region. With its unadorned clay texture and warm, nostalgic hues, Karatsu ware embodies a sense of brightness and vitality. It stands as a true expression of the essence of Japanese ceramic art—an art born from the union of earth and flame.

Ko-Karatsu and Mino Ware

Many similarities in vessel forms and decorative styles can be observed between Ko‑Karatsu ware and Mino ware. During the Bunroku campaign, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi encamped at Nagoya Castle, Furuta Oribe is said to have stayed in the region for about a year and a half from 1592 (Bunroku 1). After the fall of the Hata clan, Terasawa Hirotaka, Shima‑no‑Kami, became the lord of the newly established Karatsu Domain. As he was both a fellow disciple of Oribe in the tea tradition and originally from Mino, their relationship is believed to have been particularly close. Against this background, some scholars have suggested that Oribe may have provided guidance to the kilns in the Karatsu region. However, it is more plausible that the influence stemmed not from Oribe’s direct instruction but rather from the broader impact of Mino ceramic traditions. Among the kilns known for producing kutsu‑chawan (distorted tea bowl) in Karatsu are the Kameya-no-Tani kiln (Matsuura‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Okawabaru kiln (Matsuura‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Koraidani kiln (Taku‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Uchida-Saraya kiln (Takeo‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Ushiishi kiln (Hirado‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), Shokodani kiln (Hirado‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu), and Rishokoba kiln (Hirado‑lineage Ko‑Karatsu). It is believed that Kato Kagenobu visited many of these principal kilns. It is also noteworthy that the multi‑chamber climbing kiln (renbo‑shiki noborigama) was transmitted from Karatsu to Mino, where it was constructed at the Kujiri Motoyashiki site. The influence of Korean ceramic technology introduced to Japan during this period was profound and transformative for the development of Japanese kiln culture.