This Aka-Shino sake cup captivates with its fiery scarlet hue. At the age of three, Kitaoji Rosanjin was carried on his sister’s back through Mount Jingūji, where vivid crimson azaleas bloomed in dazzling profusion. That striking vision etched itself deep into his memory, endowing the color red with profound personal meaning. The red that resides in Shino ware reflects Rosanjin’s refined aesthetic and sensibility—his spirit quietly lives on within its glaze.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 251028-1

- Artist

- Kitaoji Rosanjin

1883 - 1959

- Weight

- 48 g

- Width

- 4.3 cm

- Height

- 4.0 cm

- Base Diameter

- 3.4 cm

- Description

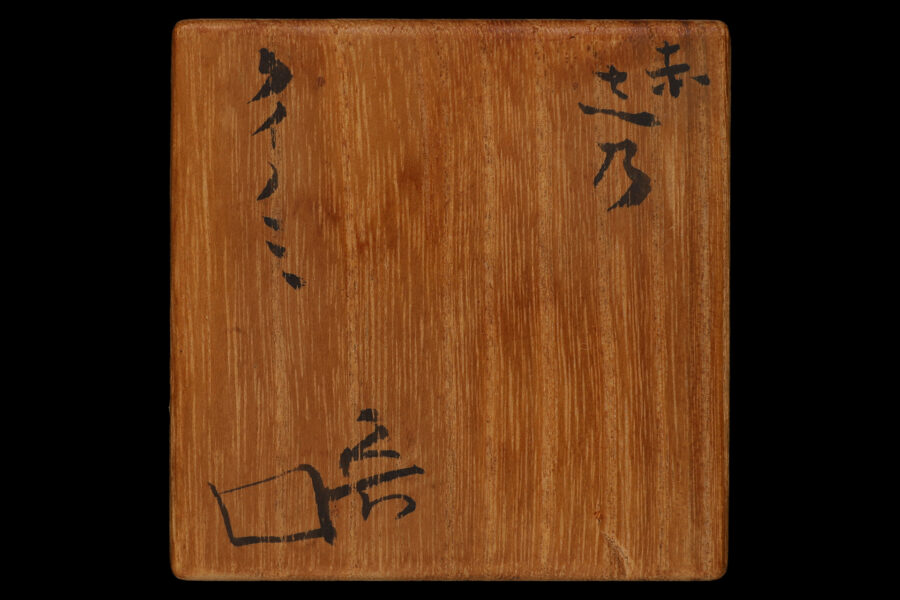

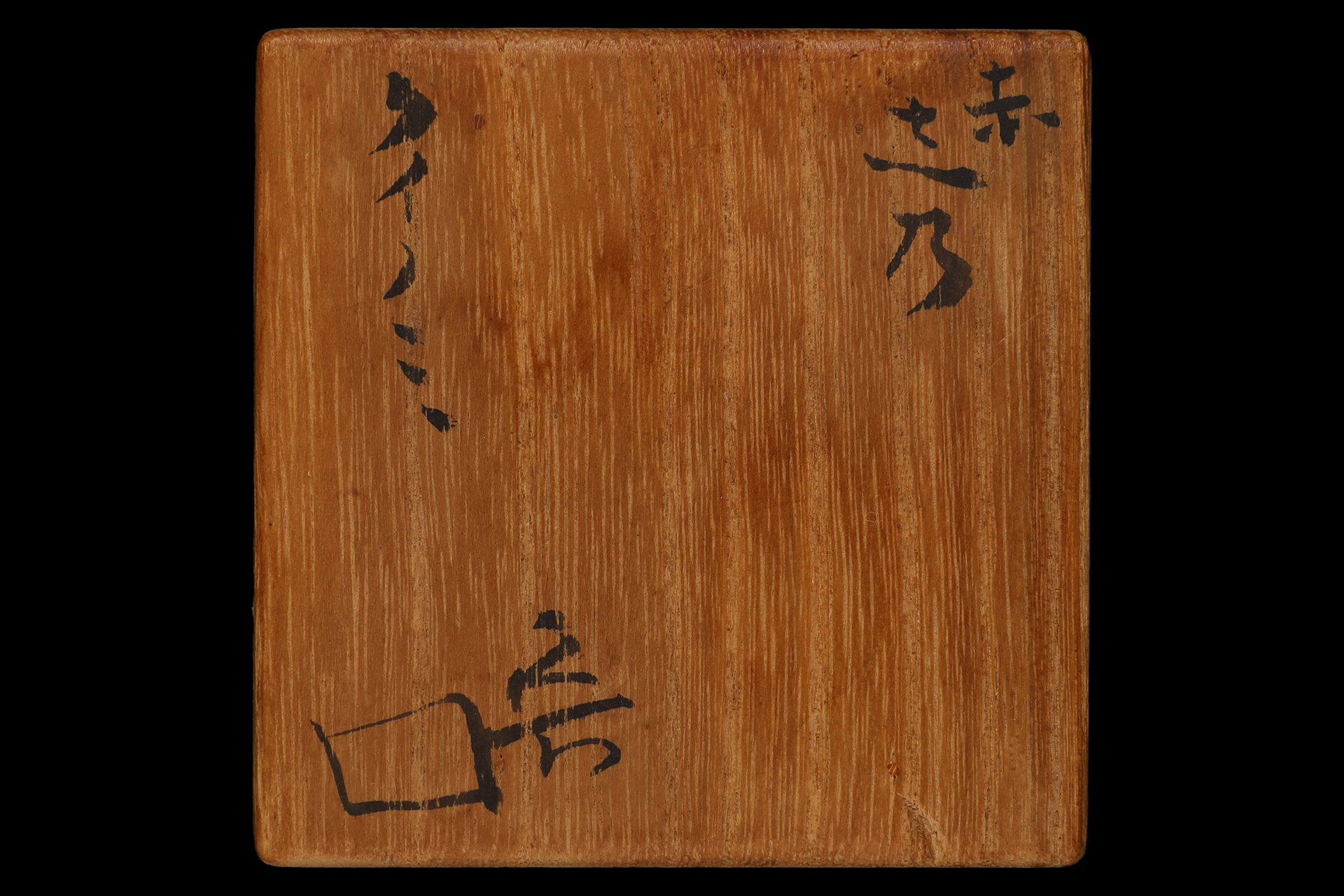

- Tomobako (Original Box with the Artist’s Inscription)

- Condition

- Intact

It remains in excellent condition.

Kitaoji Rosanjin was a once-in-a-generation genius who, with a fresh sensibility and unparalleled talent, pursued the pinnacle of beauty by uniting diverse forms of art—including calligraphy, seal engraving, cuisine, ceramics, painting, and lacquerware.

Rosanjin once remarked, “Fine tableware and furnishings make food taste better.” Throughout his life, he pursued vessels worthy of elevating the true essence of cuisine. By continually seeking harmony between dish and vessel, the act of handling fine tableware becomes a joy, and an inseparable bond is formed between food and its container.

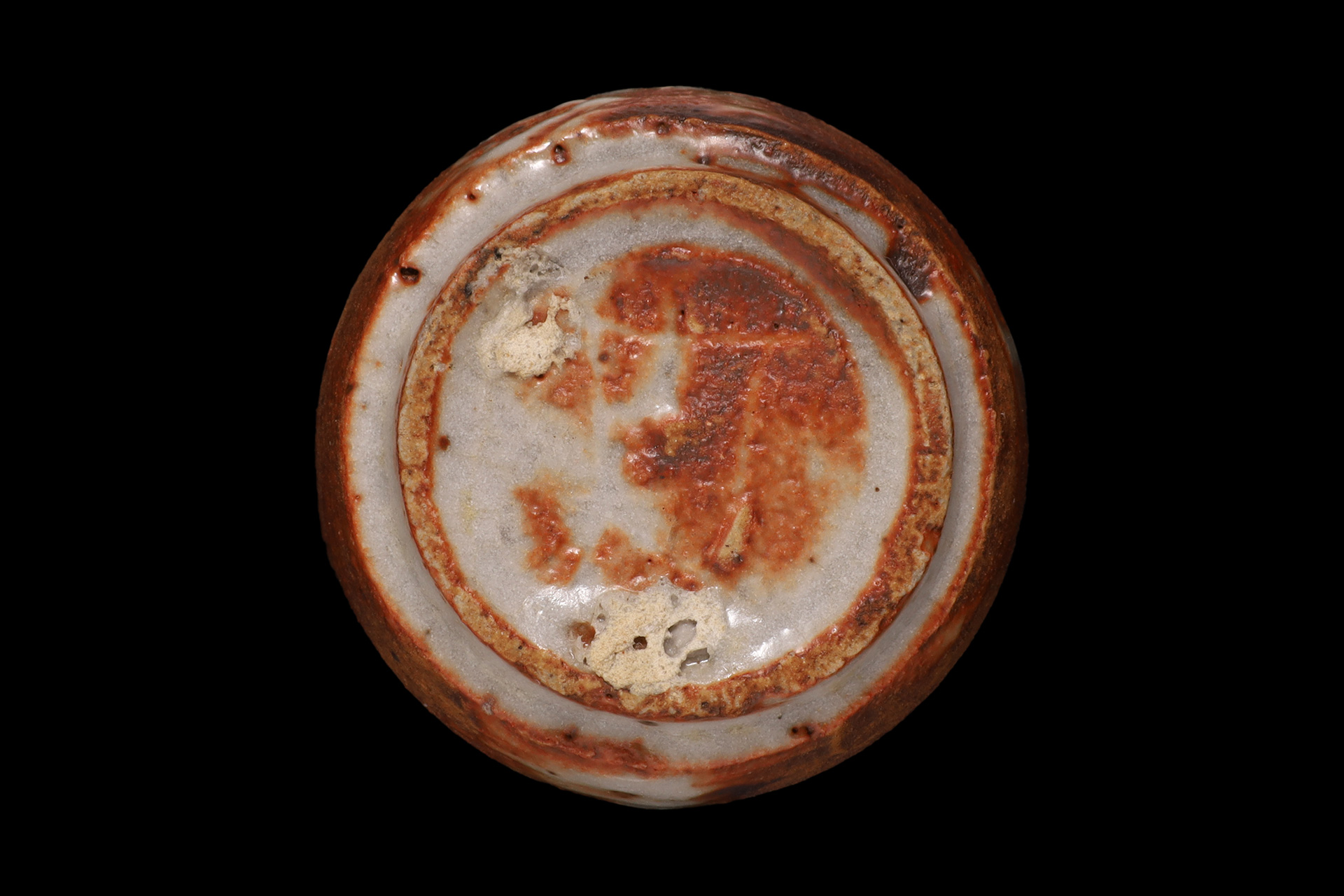

Though small enough to rest in the palm, this Aka Shino sake cup exudes a dignified and solitary presence, and is counted among Rosanjin’s most iconic works. Fired in intense flames, the slip-coated oniita bears a scorched scarlet hue, while the foot reveals a clearly incised “Ro” mark, emblematic of the artist’s hand.

In his youth, Rosanjin became an apprentice to the calligrapher Okamoto Katei, and through rigorous self-study, he delved deeply into classical Chinese calligraphy—absorbing the styles of Wang Xizhi of the Eastern Jin, and Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang, and Yan Zhenqing of the Tang dynasty. Drawn to the inner beauty inherent in the forms of Japanese calligraphers as well, he eventually forged a distinctive style of his own. This expressive brushwork is vividly displayed on tomobako (original box with artist’s inscription), serving not only as a mark of authenticity but also as a crystallization of artistic value.

Kitaoji Rosanjin 1883 – 1959

Kitaoji Rosanjin was a figure who inspired both praise and criticism, yet he displayed remarkable talent as a painter, seal engraver, calligrapher, chef, ceramic artist, and lacquer artist, leaving outstanding achievements in each field. Although his reputation declined in his later years and his works seemed destined to fade into obscurity after his death, the “Rosanjin boom” that arose in the United States and later returned to Japan led to a renewed appreciation of his artistic value, and the prices of his works rose rapidly. With his keen eye for antique ceramics and his relentless pursuit of fine cuisine and the ideal vessel, he delved deeply into the beauty and essence of Japanese cuisine—an approach symbolized by his famous phrase, “The vessel is the kimono of the cuisine.” His innovative endeavors laid a firm foundation for today’s Japanese culinary culture, and his contributions to elevating public interest in both food and tableware are immeasurable. Rosanjin’s artistic style combines elegance and depth with a free‑spirited sense of form. Among his works, pieces such as the raku ware bowl with painted camellias and his Oribe and Bizen platter dishes most vividly express his unique aesthetic sensibility. He is also widely known as the model for Kaibara Yuzan in the manga Oishinbo, and he continues to exert a powerful influence as a solitary, iconic presence in the worlds of art and cuisine.

Early Life

Kitaoji Rosanjin was born in Kyoto Prefecture as the second son of Kitaoji Kiyoaya, a member of the hereditary priestly family of Kamigamo Shrine. His given name was Fusajiro, and he later adopted several art names, including Kaisa, Rokei, Rosanjin, and Mukyo. According to accounts handed down, he was the child of an illicit relationship involving his mother, Tome. When Kiyoaya learned of this, he took his own life before Fusajiro was born. Because of these unusual and tragic circumstances, he was placed in foster care immediately after birth and spent his early years moving from one foster household to another.

In 1889 (Meiji 22), he was adopted by the woodblock carver Takezo Fukuda.

After graduating from Umeya Elementary School in 1893 (Meiji 26), he began working as an apprentice at the traditional Chinese medicine shop Chisaka Wayakuya in Nijo-Karasuma.

In 1895 (Meiji 28), he was deeply moved by a Japanese-style painting by Takeuchi Seiho (then known as Seiho) at the Fourth National Industrial Exhibition, which inspired him to pursue a career as a painter.

In 1896 (Meiji 29), he left his apprenticeship and asked his adoptive father for permission to enter the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting, but his request was denied. He instead assisted with the family’s woodblock printing work.

In 1897 (Meiji 30), he purchased practical encyclopedias such as Shoho Jizai and various model calligraphy books, turning his aspirations toward becoming a calligrapher.

Blossoming of His Calligraphic Talent

In 1899 (Meiji 32), his income increased through work painting Western-style signboards, and neighbors began calling him “sensei.”

In 1904 (Meiji 37), he received the First-Class Second Prize at the Japan Art Exhibition, and the award-winning work was purchased by Viscount Mitsuaki Tanaka, Minister of the Imperial Household.

In 1905 (Meiji 38), he studied under the copyist Okamoto Katei, adopted the name Fukuda Kaitsu, and became a document clerk at the Imperial Life Insurance Company.

In 1907 (Meiji 40), he became independent from Katei, took the name Fukuda Otei, and set up a signboard advertising himself as a calligraphy instructor.

In 1908 (Meiji 41), he married Tami Yasumi. Around this time, he became acquainted with Rihachi Fujii of the long‑established bookseller Matsuyamado, through whom he met Rihachi’s daughter, Seki.

In 1910 (Meiji 43), he traveled to Keijo (Seoul) in Korea with his mother, Tome.

In 1911 (Meiji 44), he became a secretary at the Kyoryu Printing Bureau in Korea.

In 1912 (Meiji 45), he met the renowned artist Wu Changshuo in Shanghai.

In 1913 (Taisho 2), he adopted the name Taikan, meaning “to look broadly over the world,” and while running a calligraphy school, he gained recognition for his calligraphy and seal engraving. At the Shibata residence, he met his long‑admired painter Takeuchi Seiho, who commissioned him to carve a personal seal.

In 1914 (Taisho 3), he divorced Tami by mutual consent.

In 1915 (Taisho 4), he returned to using the surname Kitaoji. He then became a guest of Hosono Entai in Kanazawa and, through Entai, attempted creating his own blue‑and‑white and red‑enameled ceramics under Suda Seika.

In 1916 (Taisho 5), he married Seki Fujii.

He subsequently used the names Kitaoji Taikan and Kitaoji Rokei.

“Taigado Art Shop” and the “Gourmet Club”

In 1917 (Taisho 6), he became acquainted with Takeshiro Nakamura.

In 1919 (Taisho 8), he and Takeshiro Nakamura founded the Taigado Art Gallery in Kyobashi, Tokyo. He moved to a rented house near Engaku-ji in Kita-Kamakura. Around this time, he began using the name “Rosanjin.”

In 1920 (Taisho 9), the gallery was renamed Taigado Art Shop. At Taigado Art Shop, he began serving food on antique ceramics that were sold in the shop.

In 1921 (Taisho 10), he established the members‑only Gourmet Club on the second floor of the Taigado Art Shop. He moved to Meigetsudani in Kita-Kamakura.

In 1922 (Taisho 11), he began producing tableware for the Gourmet Club at the Suda Seika kiln and the Miyanaga Tozan kiln. He formally inherited the Kitaoji family estate and adopted the name “Rosanjin.”

In 1923 (Taisho 12), the Taigado Art Shop and the Gourmet Club were destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake. He reopened the Gourmet Club at Hana no Chaya in Shiba Park.

Opening of the Members‑Only Luxury Restaurant “Hoshigaoka Saryo”

In 1924 (Taisho 13), he produced more than 5,000 celadon and other tableware pieces—enough for one hundred guests—at the Miyanaga Tozan kiln, where he also became acquainted with Toyozo Arakawa, who was serving as the factory manager. He leased Hoshigaoka Saryo, located within the grounds of Hie Shrine on Akasaka Sannodai in Tokyo, and began renovation work. To raise funds for opening Hoshigaoka Saryo, he came up with the idea of selling Chinese antique stationery. He invited Utsumi Yoseki, an expert in Chinese stationery, to accompany him to Shanghai to visit Wu Changshuo; after returning to Japan, they sold the items and made a substantial profit.

In 1925 (Taisho 14), he opened the members‑only luxury restaurant Hoshigaoka Saryo. Takeshiro Nakamura served as president, while Rosanjin, as advisor and head chef, entertained guests and gained a strong reputation for his exceptional presentation of dishes and tableware. The establishment quickly grew its membership, becoming a prominent social venue for government officials, business leaders, and political figures. He also became acquainted with Fujio Koyama at the Mashimizu Zoroku kiln.

Construction of the “Hoshigaoka Kiln”

In 1927 (Showa 2), in pursuit of ideal tableware for use at Hoshigaoka Saryo, he built the Hoshigaoka Kiln in Yamazaki, Kamakura City, Kanagawa Prefecture. He appointed Toyozo Arakawa of the Miyanaga Tozan kiln as chief of the kiln. On the kiln grounds, he constructed the Old Ceramics Reference Hall, where Rosanjin’s collection of ceramics was displayed, as well as the tearoom Mukyo‑an, and he hung a sign reading “Rosanjin Ceramic Art Research Institute – Hoshigaoka Kiln.” He divorced Seki by mutual agreement and married Kiyo Nakajima. With the motto “Zahen Shiyu” (“learning from the objects and friends around one’s seat”), he developed a wide range of ceramic works, seeking aesthetic ideals not only in Mino ware—such as Oribe, Shino, and Kiseto—but also in Kyoto ware traditions represented by Kenzan, Ninsei, and Dohachi.

In 1928 (Showa 3), he had the honor of receiving a visit from Prince and Princess Kuninomiya at the kiln.

In 1929 (Showa 4), Mishima Kaiun, president of Calpis, opened Gin Saryo in Ginza as a branch of Hoshigaoka Saryo.

In 1930 (Showa 5), when Toyozo Arakawa discovered Shino pottery shards at Mutabora in Ogaya, Rosanjin traveled to the site and published Hoshigaoka, focusing on the discovery of ancient Mino kilns.

In 1933 (Showa 8), Gin Saryo became a directly managed branch of Hoshigaoka Saryo.

In 1935 (Showa 10), he opened Osaka Hoshigaoka Saryo, which was well received by gourmets in the Kansai region. Although the business expanded—such as bringing the Calpis president’s Gin Saryo under direct management—his relationship with Takeshiro Nakamura began to deteriorate over differences in management policy. With the first firing of a large Seto‑style climbing kiln, he succeeded in recreating Momoyama‑period ceramics such as Shino, Oribe, and Kiseto. Membership at Hoshigaoka Saryo grew to several thousand, leading to the saying, “One who is not a member of Hoshigaoka is not a distinguished person of Japan.”

In 1936 (Showa 11), he received a notice of dismissal from Takeshiro Nakamura on the grounds of lax management. He replaced the signboard with “Rosanjin Elegant Ceramic Art Research Institute” and resolved to devote himself solely to ceramic creation based at the Hoshigaoka Kiln. Around this time, he gradually stopped using the name “Rokei.”

Ceramics‑Centered Life Based at the Hoshigaoka Kiln

Seeing Rosanjin lose confidence after his dismissal, Kinya Nagao of Wakamoto and executives of companies that had supported him commissioned him to create ceramics for gifts, gradually helping him regain his self‑assurance.

In 1938 (Showa 13), Kiyo eloped with a former craftsman of the Hoshigaoka Kiln, and they divorced. He opened the Sankai Club in the basement food department of the Shirakiya Main Store in Nihonbashi, where he procured and sold rare delicacies from the mountains and sea. Around this time, he began to develop a deep admiration for Ryokan. He married Mume Kumada.

In 1939 (Showa 14), he divorced Mume by mutual agreement. He produced large quantities of ceramics and lacquerware for use in traditional inns and restaurants. Notably, establishments such as Fukudaya in Tokyo and Hasshoukan in Nagoya became famous as restaurants associated with Rosanjin.

In 1940 (Showa 15), he married Nakamichi Nakano (the geisha Umeka). He devoted himself to painting.

In 1942 (Showa 17), he divorced Nakano and never remarried thereafter.

The Wartime Period

In 1943 (Showa 18), as wartime conditions intensified and material controls tightened, he found himself unable to use fire and therefore immersed himself in urushi lacquer work.

In 1945 (Showa 20), the Osaka Hoshigaoka Saryo, the Tokyo Hoshigaoka Saryo, and the Gin Saryo were all destroyed in air raids. A decade‑long dispute over assets with Takeshiro Nakamura was finally settled out of court (the Hoshigaoka Kiln went to Rosanjin, while their collection was divided equally).

In 1947 (Showa 22), Toyoko Jono opened Kadokado Bibo, an exclusive shop for Rosanjin’s works, in Ginza. As Rosanjin’s works began attracting the attention of occupying forces’ officers, his mindset—previously focused solely on Japanese patrons—underwent a major transformation, leading him toward a more global outlook. Yutaka Mafune and others formed the art appreciation society Seishin Club around Rosanjin.

In 1948 (Showa 23), the Rosanjin Craft Studio was established. The Hoshigaoka Kiln, which had been inactive during the war, resumed operations.

Later Years

In 1949 (Showa 24), he began visiting the kiln of Kaneshige Toyo in Imbe frequently.

In 1951 (Showa 26), at the Exhibition of Contemporary Japanese Ceramics and Paintings in Vallauris in southern France, Picasso highly praised Rosanjin’s Beni-Shino dish.

In 1952 (Showa 27), he visited Kaneshige Toyo’s kiln in Imbe together with Isamu Noguchi and produced Bizen works.

In 1953 (Showa 28), Kaneshige Toyo and Fujiwara Kei visited his kiln, and he built a Bizen-style kiln on the grounds of his own residence.

In 1954 (Showa 29), encouraged by Isamu Noguchi, he accepted an invitation from Rockefeller, then president of the Japan–America Society, and traveled throughout the United States with about 200 works, giving lectures and holding exhibitions. His works were well received at institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

In 1955 (Showa 30), through the introduction of Maeda Yusai, he met Kiichiro Zenta of Zenta Shoundo. He was recommended for designation as a Living National Treasure for Oribe ware, but he declined.

In 1959 (Showa 34), he passed away from cirrhosis of the liver caused by schistosomiasis.