Kakiemon Small Jar with Plum, Chrysanthemum, Cherry Blossom Design(Edo Period)

Sold Out

Commonly referred to as a spittoon - a vessel for receiving saliva or phlegm - this piece was, in Japan, embraced as an element of interior decoration. In some traditions, it is also known as a melon jar, said to have been used for storing watermelon seeds. Crafted in the nigoshide, the jar features a warm, milky-white porcelain base that enhances the brilliance of overglaze enamels. However, the production yield for such works was notably low, as the process required meticulous removal of impurities and the execution of highly refined techniques. Especially for complex and unusual forms such as this, the technical demands were considerable, resulting in a high rate of loss during firing. It is therefore presumed that, even in its time, this work was regarded as a rare and luxurious work - difficult to obtain and reserved for the discerning few.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 250629-2

- Period

- Edo Period

Late 17th century

- Weight

- 205g

- Width

- 10.8cm

- Height

- 6.8cm

- Base Diameter

- 4.7cm

- Accompaniments

- Paulownia box

- Condition

- Intact

The work embodies the essential qualities of a superior work - refined tension in form, exquisite glaze, and exceptional preservation.

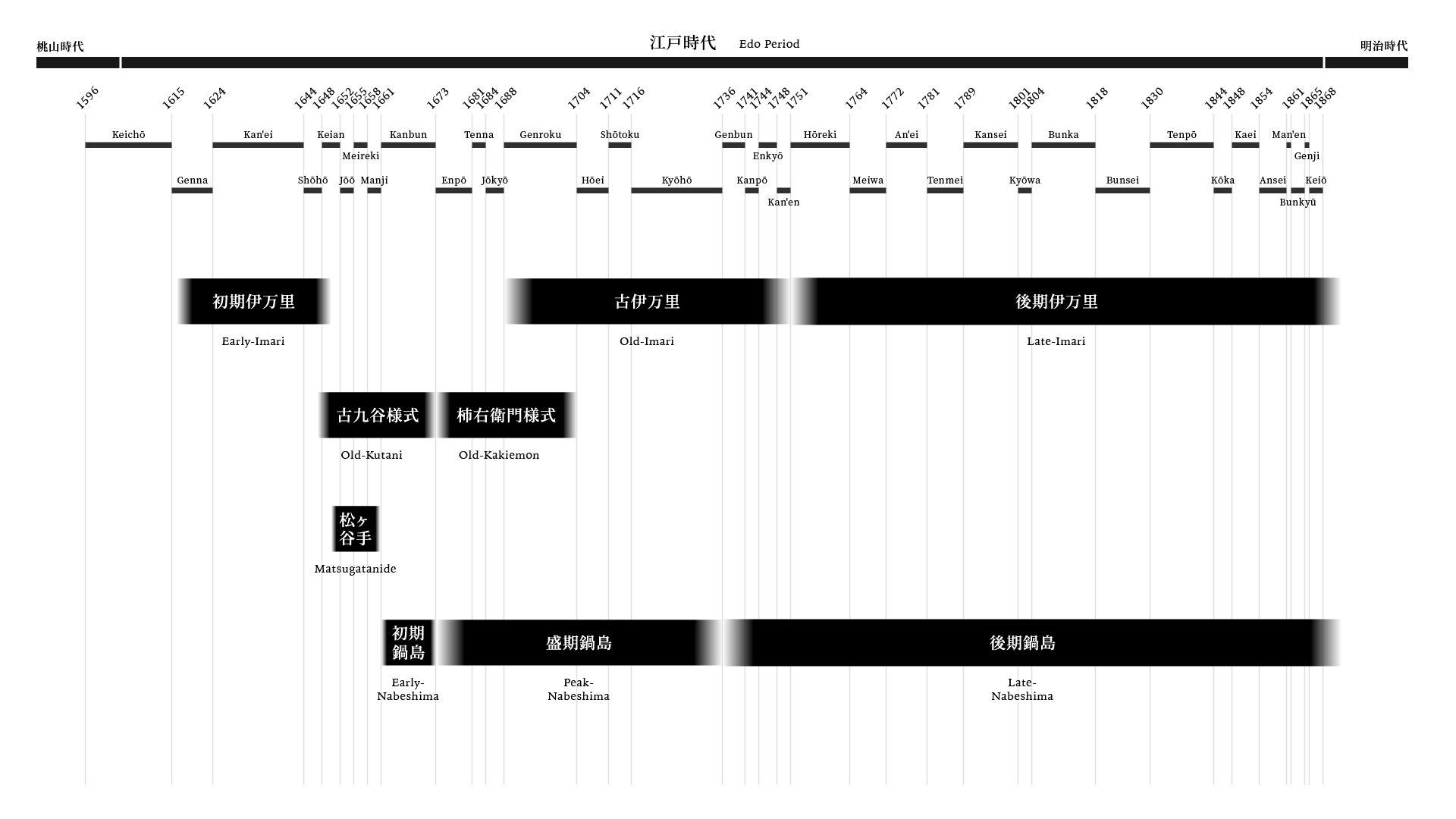

Kakiemon

Kakiemon Style refers to a distinctive category of Imari ware primarily fired during the Enpō Era (1673–81). These works were not exclusively produced by the Kakiemon family; rather, they emerged as a collective response to large-scale export orders from the Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.), and were completed across various kilns in Hizen Arita. The term “style” thus denotes a broader aesthetic, now widely recognized as “Kakiemon” in its extended sense. Characterized by refined compositions that embrace negative space and delicate brushwork by skilled painters, these porcelains possess an elegant and noble beauty. Their exquisite craftsmanship captivated European royalty and aristocracy, earning enduring popularity among the V.O.C.’s cargo offerings. Among the most celebrated features is the nigoshide body – a soft, milky-white porcelain base that heightens the brilliance of overglaze enamels. This innovation profoundly influenced the development of European porcelain, notably at Meissen and Chantilly. Signatures often include the stylized “uzu-fuku (spiral-fuku)” mark, where the character for “fortune” is rendered in a swirling motif. Other marks such as “kin (gold)” and “inishiebito (ancient person)” appear on particularly fine examples. While exported Ko-Imari ware from the Edo period also displayed opulent beauty, it was the Kakiemon style that drew the greatest admiration. After World War II, many works that had journeyed to Europe were repatriated in large numbers. The sheer volume of exported works far exceeds the domestic legacy, underscoring the style’s original purpose as an export commodity. Notably, works that blur the distinction between Ko-Imari and Kakiemon styles are often referred to as Kakiemon-de. In recent years, the term “Kakiemon” has come to be applied more broadly – even to later works of lesser refinement – reflecting evolving perceptions of the style.

https://tenpyodo.com/dictionary/kakiemon/

Nigoshide

The technique known as “Nigoshide”, emblematic of the peak of the Kakiemon-style, derives its name from the Saga dialect word nigoshi, meaning “rice-washing water”. True to its name, it is distinguished by a warm, milky-white porcelain base. Internationally, it came to be known as “Milky-White” and was highly esteemed as an ideal white porcelain that accentuates the vividness of overglaze enamel decoration. Unlike standard white porcelain or blue-and-white porcelain, Nigoshide lacks any bluish tint. Its soft-toned surface harmonizes with the painter’s brushwork and the intentional use of blank space, giving rise to the graceful chromatic beauty unique to the Kakiemon tradition. To achieve this refined base, impurities such as iron must be meticulously removed from the porcelain stone and glaze materials. The glaze is applied in an exceptionally thin layer, and as a rule, Nigoshide is not used in combination with underglaze blue decoration. According to the “Doai-chō” (Clay Composition Ledger) handed down in the Sakaida family, dated 1690, the blend ratio for the Nigoshide base was recorded as 6:3:1, using ceramic stones from Izumiyama, Shirakawa, and Iwayagawachi respectively. Due to differing shrinkage rates during firing, many works were damaged – only about 50% of flat wares such as dishes, and roughly 20% of three-dimensional forms like jars, were successfully completed. This low yield is considered one of the reasons Nigoshide production eventually ceased. Nigoshide represented a supreme technical innovation developed for export to Europe, and it became established as the highest-quality white porcelain base within the Kakiemon-style. Its peak is believed to have occurred during the Enpō era (1673–81), with exemplary works likely fired at the Nangawara-Kamanotsuji kiln. Records suggest that as early as the 1650s, experimental production of porcelain bases specifically for overglaze enamel decoration had begun at the Kusunokidani kiln. However, these early attempts were marked by coarse forming and residual traces of iron, and had not yet achieved refinement. From the 18th century onward, as porcelain exports declined, Nigoshide also disappeared from production. It was not until 1953 that the Sakaida Kakiemon XII and XIII masters successfully revived the technique. The origin of the term Nigoshide remains unclear, and since it does not appear in Edo period documents, it is thought to be a modern designation, likely coined in the early Shōwa period.