This is the old-karatsu tea bowl with a large, bold shape that exudes a dignified presence. The wonderful clay and the moist, stained glaze give it a unique charm. As it has been passed down through the generations, the sharp edges of the soil at the bottom have been worn down and made smooth. It was a time when warlords, even parents and siblings, killed each other to survive, and I believe that the reason why no pottery surpassing old-karatsu has been produced until now is not only the weight of history, but also the extremely outstanding spirituality that the potters of the momoyama period held in their hearts, their reverence for nature, their state of mind of self reflection, and their determination to risk their lives for pottery rather than relying on tricks.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 250622-1

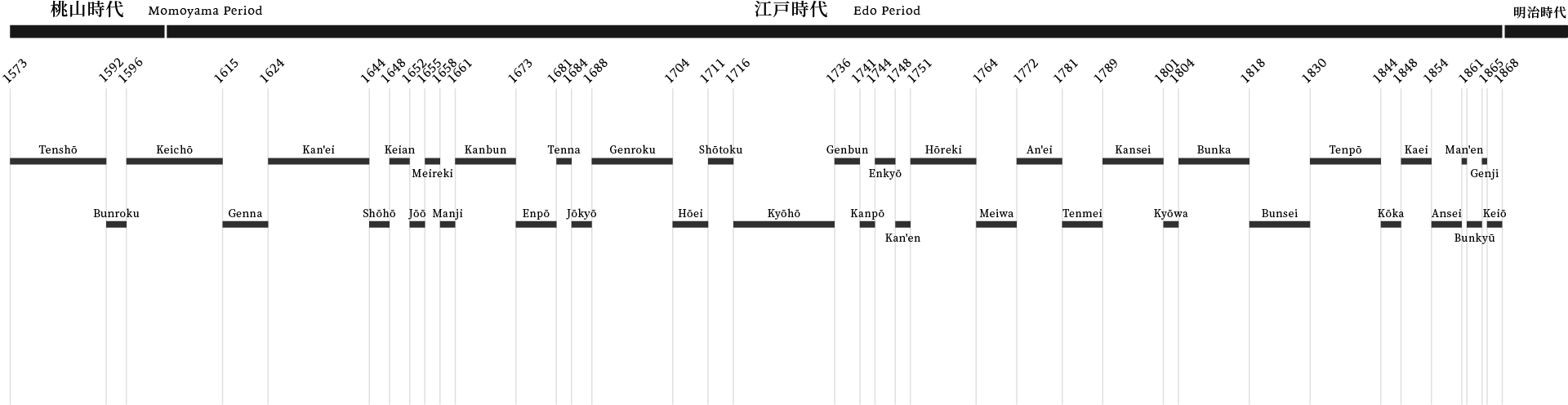

- Period

- Momoyama-Edo Period

End 16th century-Early 17th century

- Weight

- 477g

- Diameter

- 12.2cm

- Height

- 8.9cm

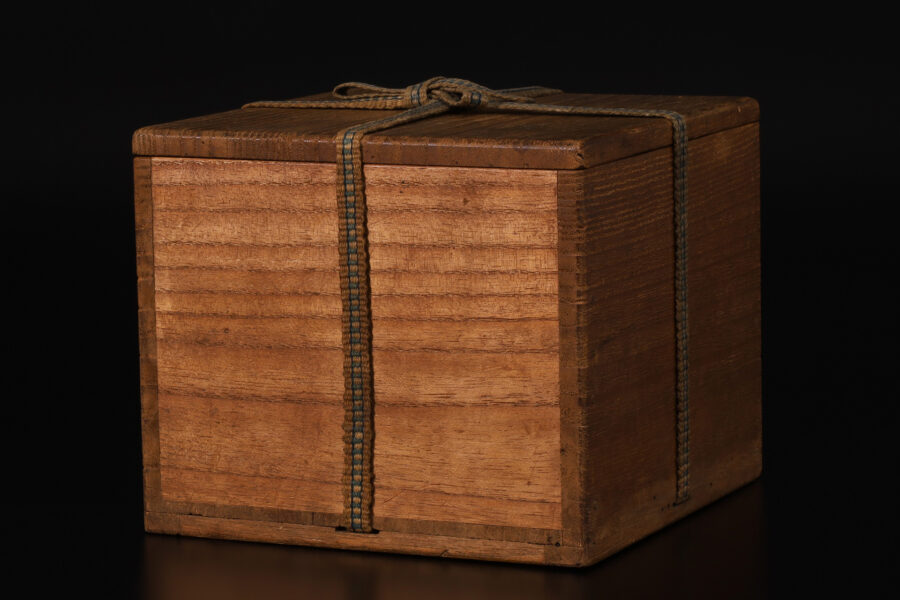

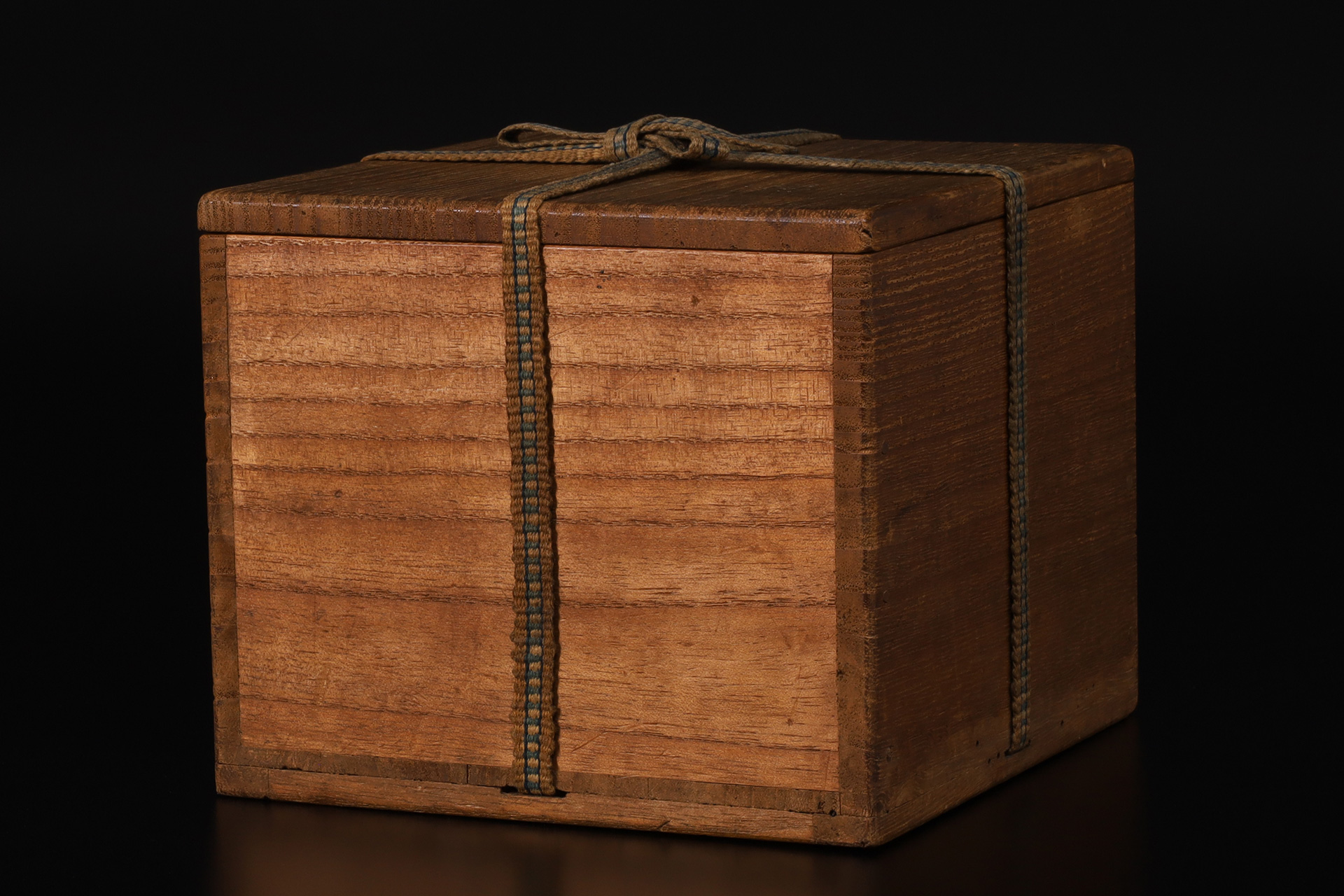

- Description

- Pouch(Shifuku)

Old-Paulownia Box

- Condition

- There is a clack and repairs at the edge

Ko-Karatsu

Karatsu ware refers to ceramics fired in the Hizen region, centered around the Karatsu Domain of Hizen Province. Its name derives from Karatsu Port, from which these wares were shipped. Highly esteemed as tea ceramics, Karatsu ware has long been cherished by tea practitioners, famously ranked as “First Raku, Second Hagi, Third Karatsu”. Its origins trace back to the late 16th century in the Kitahata area of present-day Karatsu City, Saga Prefecture. It is said that Hata Chikashi, Mikawa-no-kami, lord of Kishidake Castle, invited Korean potters to establish kilns. The castle town of Kishidake still bears traces of these early kiln sites, marking the foundational period of Karatsu ware. In 1593 (Bunroku 2), the Hata clan was dispossessed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, leading to the dispersal of Kishidake potters across Hizen—a disruption known as the “Kishidake Collapse”. Subsequently, Terazawa Hirotaka, Shima-no-kami entered the domain, establishing the Karatsu Domain. This upheaval and the closure of kilns provide compelling evidence that Karatsu ware was already being produced prior to 1593, likely during the Tenshō era (1573–92). The arrival of Korean potters during the Bunroku and Keichō campaigns (1592–98) brought advanced techniques that ushered in a flourishing period for Karatsu ware from the Momoyama into the early Edo periods. During Hideyoshi’s encampment at Nagoya Castle, the tea master Furuta Oribe is said to have stayed for approximately a year and a half from 1592 (Bunroku 1), directly advising various Karatsu kilns. The chambered climbing kiln (renbō-shiki noborigama), too, was transmitted from Karatsu to Mino, where it was constructed at the Kujiri Motoyashiki site. The introduction of Korean ceramic techniques had a profound and lasting impact on Japanese kiln culture. The name “Karatsu ware” first appeared in the 1602 (Keichō 7) record of Oribe’s tea gatherings, listed as “Karatsu ware dish,” and is frequently mentioned throughout the Keichō era (1596–1615). By the middle 17th century, the term “Ko-Karatsu (Old Karatsu)” had emerged, indicating that its historical value was already being recognized. While much of Karatsu ware was produced in quantity for everyday use, the rise of powdered tea preparation during the Momoyama and early Edo periods brought these wares to the attention of tea masters, who began to select them as tea ceramics. Some works were even commissioned by tea practitioners, and their rarity has earned them high acclaim. In the 17th century, the discovery of Izumiyama porcelain stone and the successful firing of porcelain by the immigrant potter Yi Sam-pyeong (Japanese name: Kanagae Sanbei) marked a turning point for Karatsu ware. The rise of Imari ware led to its decline. Although distinctive styles such as Mishima Karatsu and Nisai Karatsu emerged in the early Edo period, they could not match the allure of Ko-Karatsu. Thereafter, only the official kilns (Goyōgama), such as the “tea bowl kiln,” remained in limited operation. In the early Shōwa period, researchers including Kanehara Tōhen (1897-1951), Mizumachi Wasaburō (1890-1979), and Furutachi Kuichi (1874-1949) advanced the study of Ko-Karatsu. Their excavations across the Hizen region uncovered tens of thousands of ceramic shards from ancient kiln sites.

https://tenpyodo.com/en/dictionaries/ko-karatsu/

Eighty Percent Crafted by the Artisan, Twenty Percent Completed by the User

Ko-Karatsu gradually absorbs tea stains and moisture, deepening its scenery and nurturing a gentle, moist elegance. As the saying goes, “Eighty percent crafted by the artisan, twenty percent completed by the user,” the true charm of Ko-Karatsu lies in its maturity through use, allowing one to savor the vessel’s evolving journey. Especially in pieces with a softer firing, where the glaze has not fully melted, this tendency becomes even more pronounced, and features such as rain marks enhance the vessel’s presence with distinctive character.