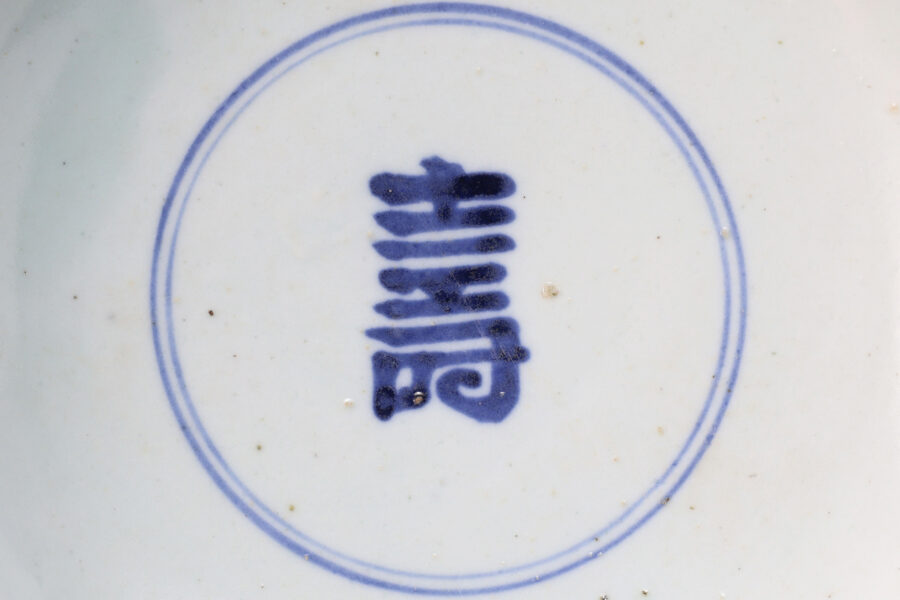

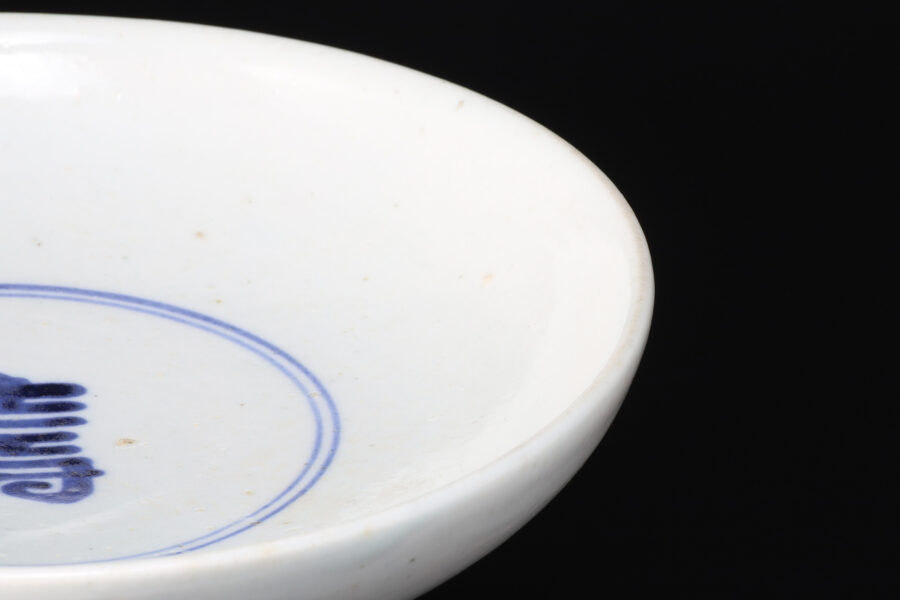

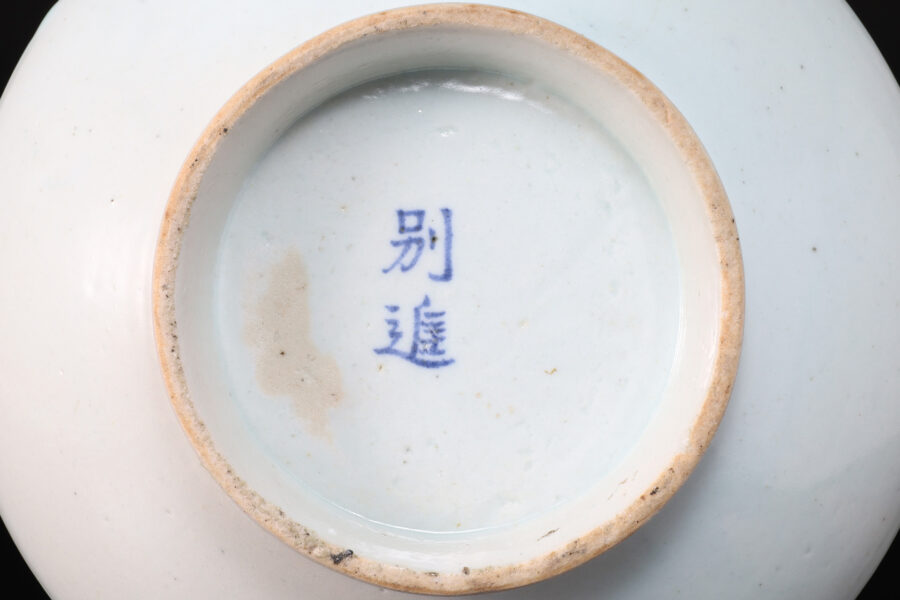

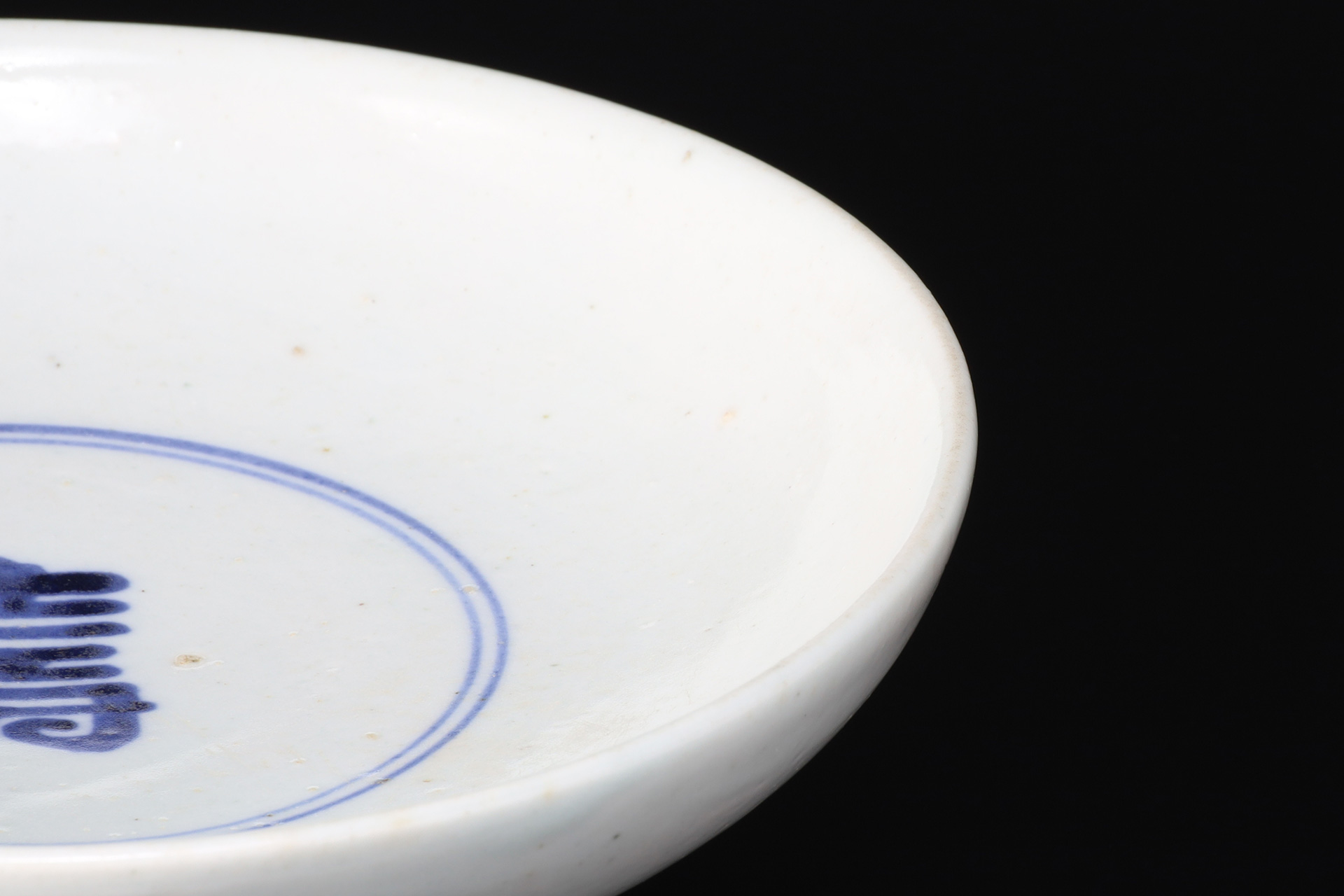

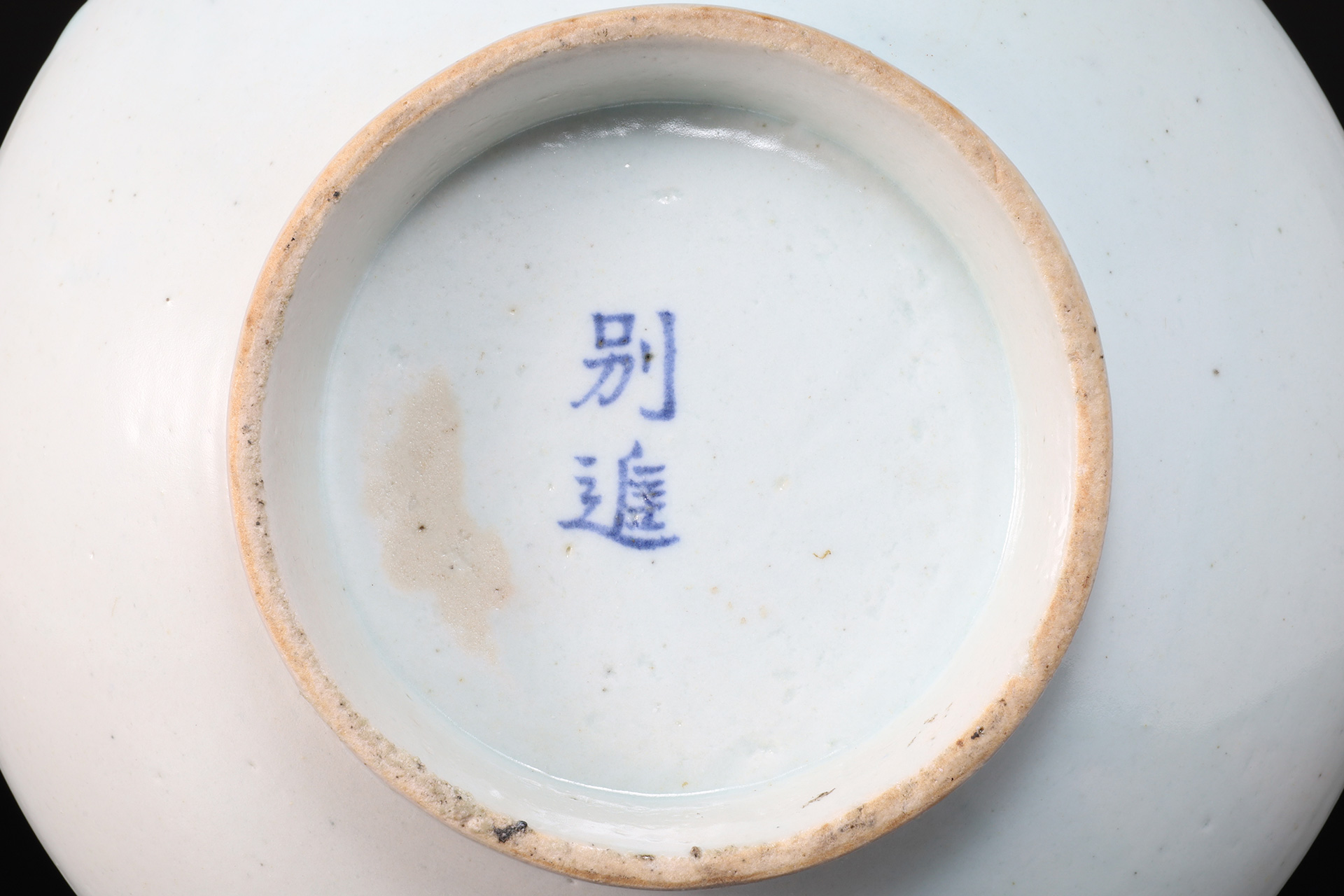

This is the excellent work from the late joseon dynasty, featuring the theme of felicitation. It is the thick, sturdy dish, heavy, with a deeply hollowed base and the glaze on the bottom has been carefully wiped off. Based on the inscription on the bottom, it is thought to be the special gift work, and the texture of the high quality pale blue and white porcelain perfectly conveys the charm of the imperial-kiln.

Inquiry

- Product Code

- 241121-1

- Period

- Joseon Dynasty

19th century

- Weight

- 1,040g

- Diameter

- 21.2cm

- Height

- 6.4cm

- Bottom Diameter

- 11.9cm

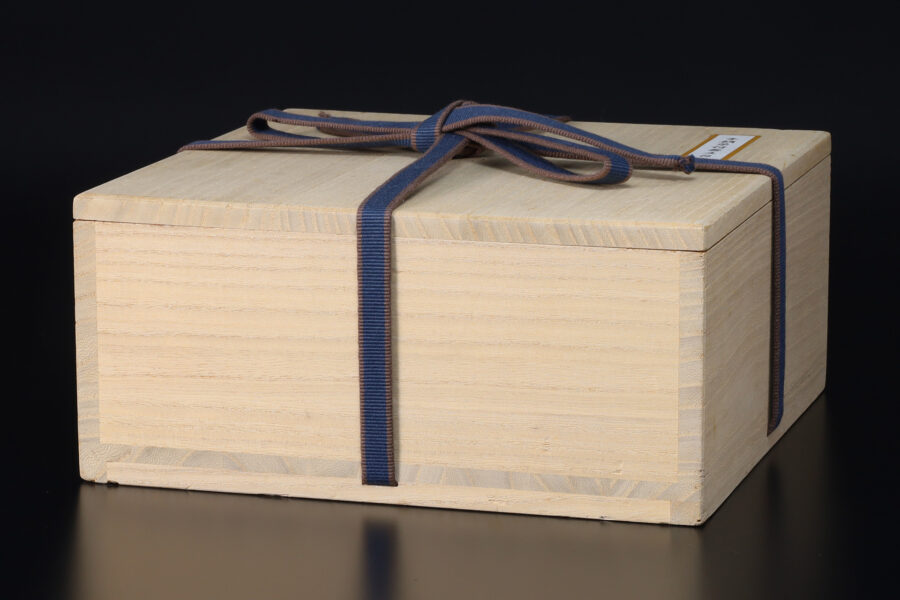

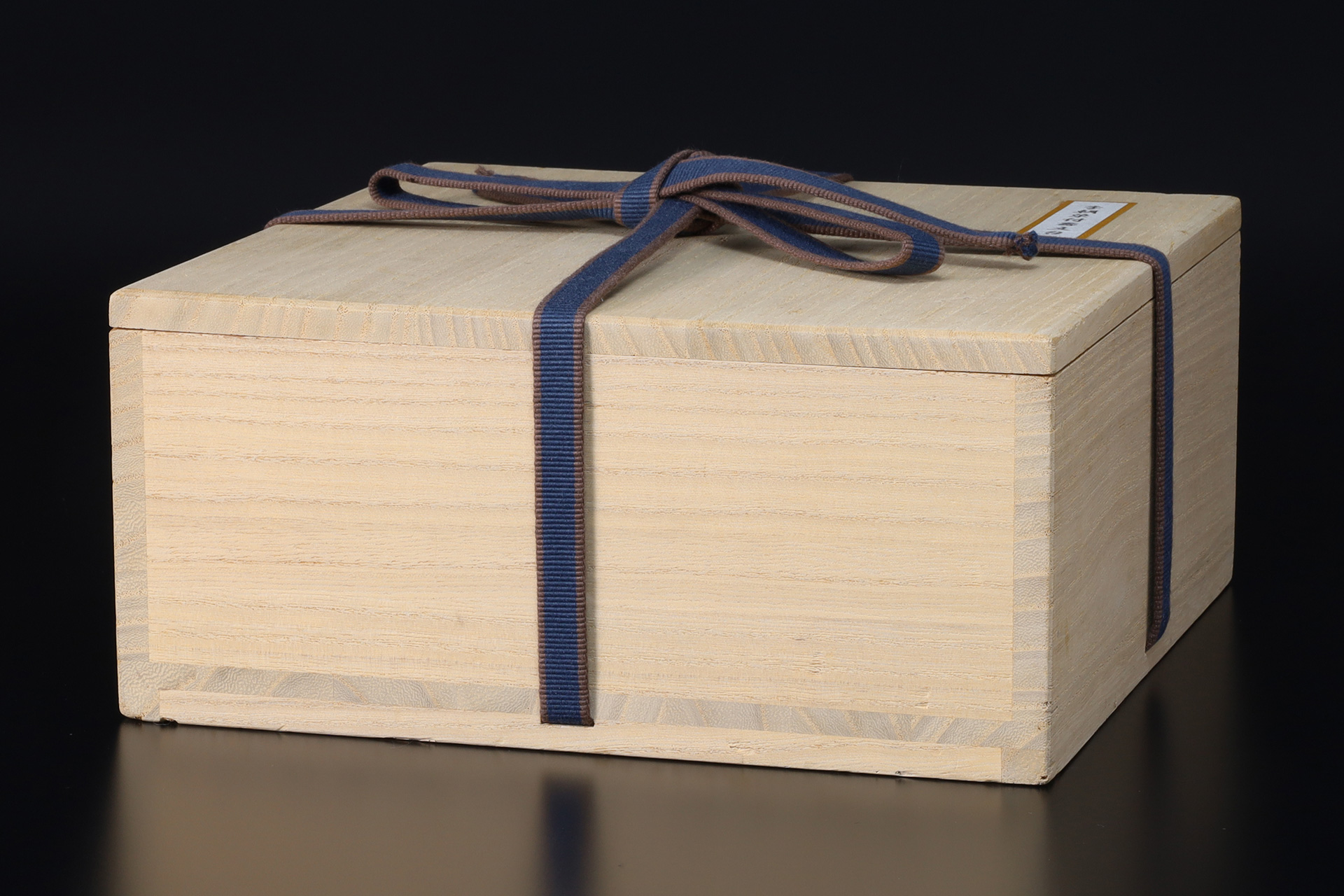

- Description

- Paulownia Box

- Condition

- Excellent Condition

It has beautiful bluish glaze, and is in good condition.

Joseon Dynasty

The Joseon Dynasty was the last unified dynasty of Korea, founded by Yi Seong-gye in 1392 on the Korean Peninsula. The country’s name was adopted in 1393 after Yi Seong-gye requested recognition from the Ming emperor. The name “Yi Dynasty” has become established in Japan and has long been used. As Buddhism, which had flourished during the Goryeo Dynasty, declined and policies to suppress Buddhism and revere Confucianism were promoted, the spirit of Confucianism became deeply ingrained as the code of conduct for people’s lives, and the ideals were to revere purity and innocence and to cultivate a simple, frugal spirit. As Confucianism spread, rituals were also held on a grand scale, from the imperial court to the general public, and white porcelain was highly valued for ritual vessels, as “White” was a pure and innocent color that symbolized holiness and simplicity. Decorations such as blue-and-white, iron-glaze, and copper-red-glaze were created based on white porcelain, but under a system that valued frugality, colored decoration were never fired until the end. In 1897, after the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), the country’s name was changed to “Daehan”. After the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), it became a Japanese protectorate, and came to an end with the annexation of Korea in 1910. The brothers Noritaka Asakawa and Takumi had a deep understanding of and love for Yi Dynasty ceramics and played a key role in bringing them to public attention in society. It was Muneyoshi Yanagi who became interested in them under their guidance.

https://tenpyodo.com/en/dictionaries/korean/

Late Joseon period Late 18th century (1752) -19th century

In 1752, the last official kiln of the Joseon Dynasty was relocated from Geumsa-ri kiln to Bunwon kiln. The subsequent period, lasting until 1883 when Bunwon kiln transitioned from an official kiln to a private one, is known as the late Joseon period—spanning approximately 130 years. Among the various official kilns established throughout Gwangju, Bunwon kiln was situated closest to the Han River, suggesting that logistical convenience for transporting materials and finished wares was a key consideration. During this time, the importation of cobalt pigment from China became abundant, leading to a flourishing of blue-and-white porcelain production. As the era progressed, the cobalt blue tones deepened, and brushwork grew bolder. Decorative motifs included a wide array of auspicious symbols such as the Ten Longevity Symbols, lotus flowers, peonies, cranes, bats, and Chinese characters. With the rise of blue-and-white porcelain, the use of iron-brown pigment declined, ushering in the vivid crimson tones of cinnabar. In the early phase of Bunwon kiln, some works rivaled the elegance of those from Geumsa-ri kiln. However, as national strength waned, the quality of clay bodies, shaping, and decoration became increasingly coarse. The official kiln’s fixed location provided a stable production environment, benefiting from the Han River’s vast waterway. At the same time, the expansion in output reflects the limitations of relying solely on local materials to meet growing demand. During this period, Bunwon kiln served not only as a supplier of wares to the royal court but also responded to the burgeoning private demand driven by economic growth. In fact, it is said that production for general consumers was prioritized over courtly wares. Bunwon kiln produced a wide variety of vessels—from ritual implements to everyday items—with remarkable technical skill. Its distinctive character was most evident in stationery items such as water droppers and brush pots, which were avidly sought by literati, as attested by historical records and surviving masterpieces. As vessel walls thickened, plates and jars came to feature deeply recessed bases as a result of thickened walls. In the latter half of the 19th century, Korea faced successive invasions by foreign powers including the United States, France, and Japan, plunging the nation into political turmoil. In 1883, Bunwon kiln was finally privatized, marking the close of an illustrious 500-year tradition of official kilns. Following privatization—during the final years of the Joseon Dynasty—the quality of ceramics deteriorated markedly, exhibiting signs of severe decline. White porcelain took on a grayish cast, and blue-and-white porcelain became even more intensely colored, often appearing purplish.